A Crash Course in C++ and the Standard Library

The goal of this chapter is to cover briefly the most important parts of C++ so that you have a foundation of knowledge before embarking on the rest of this book. This chapter is not a comprehensive lesson in the C++ programming language or the Standard Library. Certain basic points, such as what a program is and what recursion is, are not covered. Esoteric points, such as the definition of a union, or the volatile keyword, are also omitted. Certain parts of the C language that are less relevant in C++ are also left out, as are parts of C++ that get in-depth coverage in later chapters.

This chapter aims to cover the parts of C++ that programmers encounter every day. For example, if you’re fairly new to C++ and don’t understand what a reference variable is, you’ll learn about that kind of variable here. You’ll also learn the basics of how to use the functionality available in the Standard Library, such as vector containers, optional values, string objects, and more. These modern constructs from the Standard Library are briefly introduced in this chapter so that they can be used throughout examples in this book from the beginning.

If you already have significant experience with C++, skim this chapter to make sure that there aren’t any fundamental parts of the language on which you need to brush up. If you’re new to C++, read this chapter carefully and make sure you understand the examples. If you need additional introductory information, consult the titles listed in Appendix B, “Annotated Bibliography.”

C++ CRASH COURSE

Section titled “C++ CRASH COURSE”The C++ language is often viewed as a “better C” or a “superset of C.” It was mainly designed to be an object-oriented C, commonly called as “C with classes.” Later on, many of the annoyances and rough edges of the C language were addressed as well. Because C++ is based on C, some of the syntax you’ll see in this section will look familiar to you if you are an experienced C programmer. The two languages certainly have their differences, though. As evidence, the C23 standard specification document is a little fewer than 800 pages in size, while the C++23 standard specification document is more than 2,000 pages. So, if you’re a C programmer but also if you are coming from other languages such as Java, C#, Python, and so on, be on the lookout for new or unfamiliar syntax!

The Obligatory “Hello, World” Program

Section titled “The Obligatory “Hello, World” Program”In all its glory, the following code is the simplest C++ program you’re likely to encounter. If you are using an older version of C++, then import std; and std::println() might not work. In that case, you’ll need to use alternatives discussed shortly.

import std;

int main(){ std::println("Hello, World!"); return 0;}This code, as you might expect, prints the message “Hello, World!” on the screen. It is a simple program and unlikely to win any awards, but it does exhibit the following important concepts about the format of a C++ program:

- Comments

- Importing modules

- The

main()function - Printing text

- Returning from a function

These concepts are briefly explained in upcoming sections.

Comments

Section titled “Comments”The first line of the program is a comment, a message that exists for the programmer only and is ignored by the compiler. In C++, there are two ways to delineate a comment. You can use two forward slashes to indicate that whatever follows on that line is a comment:

The same behavior (this is to say, none) can be achieved by using a multiline comment. Multiline comments start with /* and end with */. The following code shows a multiline comment in action (or, more appropriately, inaction):

/* This is a multiline comment. The compiler will ignore it. */Comments are covered in detail in Chapter 3, “Coding with Style.”

Importing Modules

Section titled “Importing Modules”Support for modules was one of the big four new features of C++20, replacing the old mechanism of header files. If you want to use functionality from a module, you simply import that module. This is done with an import declaration. Starting with C++23, you can get access to the entire C++ Standard Library by importing a single standard named module called std. The first line of the “Hello, World” application imports this standard module:

import std;If the program did not import that module, it would be unable to perform its only task of printing text.

Without C++23’s standard named module support, you have to explicitly import all individual header files that your code requires. As there are more than 100 header files in the Standard Library, it’s not always obvious to know which specific header you need to import to use a certain feature. As a reference, Appendix C, “Standard Library Header Files,” lists all header files of the C++ Standard Library including a short description of their contents. For example, instead of importing the standard named module std in the “Hello, World” application, you can import only those header files that the code really needs. In this example, the code only needs to import <print> to get access to the text printing functionality. Notice that when importing the named module std, you don’t use angle brackets, but when importing individual header files, you need to use angle brackets as follows:

import <print>;Since this is a book about C++23, this book uses modules everywhere. All functionality provided by the C++ Standard Library is provided in well-defined header files. Most examples in this book simply import the std named module, instead of individual header files, but the text always mentions in which header file certain functionality is provided.

Modules are not limited to Standard Library functionality. You can write your own modules to provide custom types and functionality, as you will learn throughout this book.

How the Compiler Processes Your Source Code

Section titled “How the Compiler Processes Your Source Code”In short, building a C++ program is a three-step process. Technically, there are a few more phases in the compilation process, but this simplified view is sufficient for now.

- First, the code is run through a preprocessor, which recognizes meta-information about the code and handles preprocessor directives, such as

#includedirectives. A source file in which all preprocessor directives are handled is called a translation unit. - Next, all translation units are independently compiled, or translated, into machine-readable object files in which references to functions and so on are not yet defined.

- Resolving those references is done in the final phase by the linker, which links all object files together into the final executable.

Preprocessor Directives

Section titled “Preprocessor Directives”If your compiler does not yet support modules, then instead of importing modules or header files, you need to #include header files. That is, explicit import declarations such as import <print>;, need to be replaced with #include preprocessor directives as follows:

#include <print>Directives aimed at the preprocessor start with the # character, as in #include <print>. In this case, the #include directive tells the preprocessor to take everything from the <print> header file and copy it into the current file. The <print> header provides the functionality to print text to the screen.

Chapter 11, “Modules, Header Files, and Miscellaneous Topics,” discusses preprocessor directives in a bit more detail. But, as mentioned, this book uses modules instead of old-style header files.

The main() Function

Section titled “The main() Function”main() is, of course, where the program starts. The return type of main() is an int, indicating the result status of the program. The main() function either takes no parameters or takes two parameters as follows:

int main(int argc, char** argv)argc gives the number of arguments passed to the program, and argv contains those arguments. Note that argv[0] can be the program name, but it might as well be an empty string, so do not rely on it; instead, use platform-specific functionality to retrieve the program name. The important thing to remember is that the actual arguments contained in argv start at index 1.

Section titled “ Printing Text”Before C++23, you would use I/O streams to output text to the screen. Streams are briefly covered in the next section and in detail in Chapter 13, “Demystifying C++ I/O.” However, C++23 introduces a new, easier-to-use mechanism to print text to the screen, which is used in almost every code snippet in this book: std::print() and println(), both defined in <print>.

Chapter 2, “Working with Strings and String Views,” discusses the std::print() and println() string formatting and printing functions in detail. However, their basic use is straightforward and introduced here so that they can already be used in upcoming code snippets. In its most basic form, println() can be used to print a line of text that automatically ends with a new line:

std::println("Hello, World!");The first argument to println() is a format string, which can contain replacement fields to be replaced with values passed in as second and subsequent arguments. You indicate where a replacement field goes by including curly brackets, {}, for each field to be included. For example:

std::println("There are {} ways I love you.", 219);In this example, the number 219 is inserted into the string, so the output is:

There are 219 ways I love you.You can have as many replacement fields as needed, for example:

std::println("{} + {} = {}", 2, 4, 6);In this example, each field is applied in order, so the resulting output is:

2 + 4 = 6There is much more to be said about the format of replacement fields, but that’s for Chapter 2.

If you use print() instead of println(), the printed text will not end with a new line character.

I/O Streams

Section titled “I/O Streams”If your compiler does not yet support the C++23 std::print() and println() functions, you have to rewrite them using I/O streams.

I/O streams are covered in depth in Chapter 13, but the basics of output and input are simple. Think of an output stream as a laundry chute for data. Anything you toss into it will be output appropriately. std::cout is the chute corresponding to the user console, or standard out. There are other chutes, including std::cerr, which outputs to the error console. The << operator tosses data down the chute. Output streams allow multiple types of data to be sent down the stream sequentially on a single line of code. The following code outputs text, followed by a number, followed by more text:

std::cout << "There are " << 219 << " ways I love you." << std::endl;Starting with C++20, though, it is recommended to use std::format(), defined in <format>, to perform string formatting. The format() function uses the same concept of replacement fields as print() and println()and is discussed in detail in Chapter 2. However, using it to rewrite the previous statement is easy enough:

std::cout << std::format("There are {} ways I love you.", 219) << std::endl;Thus, if your compiler doesn’t support print() and println() yet, you can easily rewrite such statements to use cout, format(), and endl. For example, suppose you have the following statement:

std::println("{} + {} = {}", 2, 4, 6);In this statement, replace println() with format(), stream the result to cout, and add an output of endl:

std::cout << std::format("{} + {} = {}", 2, 4, 6) << std::endl;std::endl represents an end-of-line sequence. When the output stream encounters std::endl, it will output everything that has been sent down the chute so far and move to the next line. An alternate way of representing the end of a line is by using the \n character. The \n character is an escape sequence, which refers to a new-line character. Escape sequences can be used within any quoted string of text. The following table shows the most common ones:

| ESCAPE SEQUENCE | MEANING |

|---|---|

\n | New line: moves the cursor to the beginning of the next line |

\r | Carriage return: moves the cursor to the beginning of the current line, but does not advance to the next line |

\t | Tab |

\\ | Backslash character |

\" | Quotation mark |

Keep in mind that endl inserts a new line into the stream and flushes everything currently in its buffers down the chute. Overusing endl, for example in a loop, is not recommended because it will have a performance impact. On the other hand, inserting \n into the stream also inserts a new line but does not automatically flush the buffers.

By default, print() and println() print text to the standard output console, std::cout. You can print to the error console, std::cerr, as follows:

std::println(std::cerr, "Error: {}", 6);Streams can also be used to accept input from the user. The simplest way to do so is to use the >> operator with an input stream. The std::cin input stream accepts keyboard input from the user. Here is an example:

import std;int main(){ int value; std::cin >> value; std::println("You entered {}", value);}The >> operator stops input when it encounters a space character after reading a value. That also means you cannot use the operator to read text containing spaces. Additionally, user input can be tricky because you never know what kind of data the user will enter. Chapter 13 discusses input streams in detail, including how to read text with embedded spaces.

If you’re new to C++ and coming from a C background, you’re probably wondering what has been done with the trusty old printf() and scanf() functions. While these functions can still be used in C++, I strongly recommend using the modern print(), println(), and format() functions and the streams library instead, mainly because the printf() and scanf() family of functions do not provide any type safety.

Returning from a Function

Section titled “Returning from a Function”The last line in the “Hello, World” program is as follows:

return 0;Since this is the main() function, returning from it returns control to the operating system. When doing so, it passes the value 0, which usually signals to the operating system that there were no errors while executing the program. For error cases, you can return non-zero values.

A return statement in main() is optional. If you don’t write one, the compiler will implicitly add a return 0; for you.

Namespaces

Section titled “Namespaces”Namespaces address the problem of naming conflicts between different pieces of code. For example, you might be writing some code that has a function called foo(). One day, you decide to start using a third-party library, which also has a foo() function. The compiler has no way of knowing which version of foo() you are referring to within your code. You can’t change the library’s function name, and it would be a big pain to change your own.

Namespaces come to the rescue in such scenarios because you can define the context in which names are defined. To place code in a namespace, enclose it within a namespace block. Here’s an example:

namespace mycode { void foo() { std::println("foo() called in the mycode namespace"); }}By placing your version of foo() in the namespace mycode, you are isolating it from the foo() function provided by the third-party library. To call the namespace-enabled version of foo(), prepend the namespace onto the function name by using ::, also called the scope resolution operator, as follows:

mycode::foo(); // Calls the "foo" function in the "mycode" namespaceAny code that falls within a mycode namespace block can call other code within the same namespace without explicitly prepending the namespace. This implicit namespace is useful in making the code more readable. You can also avoid prepending of namespaces with a using directive. This directive tells the compiler that the subsequent code is making use of names in the specified namespace. The namespace is thus implied for the code that follows:

using namespace mycode;

int main(){ foo(); // Implies mycode::foo();}A single source file can contain multiple using directives, but beware of overusing this shortcut. In the extreme case, if you declare that you’re using every namespace known to humanity, you’re effectively eliminating namespaces entirely! Name conflicts will again result if you are using two namespaces that contain the same names. It is also important to know in which namespace your code is operating so that you don’t end up accidentally calling the wrong version of a function.

You’ve seen the namespace syntax before—you used it in the “Hello, World” program, where println is a name defined in the std namespace. You can write “Hello, World” with a using directive as shown here:

import std;

using namespace std;

int main(){ println("Hello, World!");}A using declaration can be used to refer to a particular item within a namespace. For example, if the only part of the std namespace that you want to use unqualified is print, you can use the following using declaration:

using std::print;Subsequent code can refer to print without prepending the namespace, but other items in the std namespace, such as println, still need to be explicit:

using std::print;print("Hello, ");std::println("World!");Never put a using directive or using declaration in a header file at global scope; otherwise, you force it on everyone who includes your header file. Putting it in a smaller scope, for instance at namespace or class scope, is OK, even in a header file. It’s also perfectly fine to put a using directive or declaration in a module interface file, as long as you don’t export it. However, this book always fully qualifies all types in module interface files, as I think it makes it easier to understand an interface. Module interface files and exporting entities from modules are explained later in this chapter.

Nested Namespace

Section titled “Nested Namespace”A nested namespace is a namespace inside another one. Each namespace is separated by a double colon. Here’s an example:

namespace MyLibraries::Networking::FTP { /* … */}This compact syntax was not available before C++17 in which case you had to resort to the following:

namespace MyLibraries { namespace Networking { namespace FTP { /* … */ } }}Namespace Alias

Section titled “Namespace Alias”A namespace alias can be used to give a new and possibly shorter name to another namespace. Here’s an example:

namespace MyFTP = MyLibraries::Networking::FTP;Literals

Section titled “Literals”Literals are used to write numbers or strings in your code. C++ supports a couple of standard literals. Integral numbers can be written using the following literals (the examples represent the same number, 123):

- Decimal literal,

123 - Octal literal,

0173(starts with a zero) - Hexadecimal literal,

0x7B(starts with 0x) - Binary literal,

0b1111011(starts with 0b)

Never put a zero, 0, in front of a numerical literal, unless it’s an octal literal!

Other examples of literals in C++ include the following:

- A floating-point value (such as

3.14f) - A double floating-point value (such as

3.14) - A hexadecimal floating-point literal (such as

0x3.ABCp-10and0Xb.cp12l) - A single character (such as

'a') - A zero-terminated array of characters (such as

"character array")

A literal can have a suffix, such as the f in 3.14f, to force a certain type. In this case, 3.14f results in a float, while 3.14 results in a double.

Single quote characters can be used as digit separators in numeric literals. For example:

23'456'7892'34'56'7890.123'456f

Multiple string literals separated only by whitespace are automatically concatenated into a single string. For example:

std::println("Hello, " "World!");is equivalent to:

std::println("Hello, World!");It is also possible to define your own type of literals, which is an advanced feature explained in Chapter 15, “Overloading C++ Operators.”

Variables

Section titled “Variables”In C++, variables can be declared just about anywhere in your code and can be used anywhere in the current block below the line where they are declared. Variables can be declared without being given a value. These uninitialized variables generally end up with a semi-random value based on whatever is in memory at that time, and they are therefore the source of countless bugs. Variables in C++ can alternatively be assigned an initial value when they are declared. The code that follows shows both flavors of variable declaration, both using ints, which represent integer values:

int uninitializedInt;int initializedInt { 7 };println("{} is a random value", uninitializedInt);println("{} was assigned as an initial value", initializedInt);The initializedInt variable is initialized using the uniform initialization syntax. You can also use the following assignment syntax for initializing variables:

int initializedInt = 7;Uniform initialization was introduced with the C++11 standard in 2011. It is recommended to use uniform initialization instead of the old assignment syntax, so that’s the syntax used in this book. The section “Uniform Initialization” later in this chapter goes deeper in on the benefits and why it is recommended.

Variables in C++ are strongly typed; that is, they always have a specific type. C++ comes with a whole set of built-in types that you can use out of the box. The following table shows the most common types:

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION | USAGE |

|---|---|---|

cpp (signed) int signed | Positive and negative integers; the range depends on the compiler (usually 4 bytes) | cpp int i {-7}; signed int i {-6}; signed i {-5}; |

cpp (signed) short (int) | Short integer (usually 2 bytes) | cpp short s {13}; short int s {14}; signed short s {15}; signed short int s {16}; |

cpp (signed) long (int) | Long integer (usually 4 bytes) | cpp long l {-7L}; |

cpp (signed) long long (int) | Long long integer; the range depends on the compiler but is at least the same as for long (usually 8 bytes) | cpp long long ll {14LL}; |

cpp unsigned (int) unsigned short (int) unsigned long (int) unsigned long long (int) | Limits the preceding types to values >= 0 | cpp unsigned int i {2U}; unsigned j {5U}; unsigned short s {23U}; unsigned long l {54UL}; unsigned long long ll {140ULL}; |

cpp float | Single precision floating-point numbers | cpp float f {7.2f}; |

cpp double | Double precision floating-point numbers; precision is at least the same as for float | cpp double d {7.2}; |

cpp long double | Long double precision floating-point numbers; precision is at least the same as for double | cpp long double d {16.98L}; |

cpp char unsigned char signed char | A single character | cpp char ch {'m'}; |

cpp char8_t char16_t char32_t | A single n-bit UTF-n-encoded Unicode character where n can be 8, 16, or 32 | cpp char8_t c8 {u8'm'}; char16_t c16 {u'm'}; char32_t c32 {U'm'}; |

cpp wchar_t | A single wide character; the size depends on the compiler | cpp wchar_t w {L'm'}; |

cpp bool | A Boolean type that can have one of two values: true or false | cpp bool b {true}; |

The range of signed and unsigned integer and char types is as follows:

| TYPE | SIGNED | UNSIGNED |

|---|---|---|

char | -128 to 127 | 0 to 255 |

| 2-byte integers | -32,768 to 32,767 | 0 to 65,535 |

| 4-byte integers | -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647 | 0 to 4,294,967,295 |

| 8-byte integers | -9,223,372,036,854,775,808 to 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 | 0 to 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 |

Type char is a different type compared to both the signed char and unsigned char types. It should be used only to represent characters. Depending on your compiler, it can be either signed or unsigned, so you should not rely on it being signed or unsigned.

The range and precision of floating-point types is discussed in the section “Floating-Point Numbers” later in this chapter.

Related to char, <cstddef> provides the std::byte type representing a single byte. Before C++17, a char or unsigned char was used to represent a byte, but those types make it look like you are working with characters. std::byte on the other hand clearly states your intention, that is, a single byte of memory. A byte can be initialized as follows:

std::byte b { 42 };Numerical Limits

Section titled “Numerical Limits”C++ provides a standard way to obtain information about numeric limits, such as the maximum possible value for an integer on the current platform. In C, you could access constants, such as INT_MAX. While those are still available in C++, it’s recommended to use the std::numeric_limits class template defined in <limits>. Class templates are discussed later in this book, but those details are not important to understand how to use numeric_limits. For now, you just need to know that, since it is a class template, you have to specify the type you are interested in between a set of angle brackets. For example, to get numeric limits for integers, you write std::numeric_limits<int>. Consult a Standard Library reference (see Appendix B) to learn exactly what kind of information you can query using numeric_limits.

Here are a few examples:

println("int:");println("Max int value: {}", numeric_limits<int>::max());println("Min int value: {}", numeric_limits<int>::min());println("Lowest int value: {}", numeric_limits<int>::lowest());

println("\ndouble:");println("Max double value: {}", numeric_limits<double>::max());println("Min double value: {}", numeric_limits<double>::min());println("Lowest double value: {}", numeric_limits<double>::lowest());The output of this code snippet on my system is as follows:

int:Max int value: 2147483647Min int value: -2147483648Lowest int value: -2147483648

double:Max double value: 1.7976931348623157e+308Min double value: 2.2250738585072014e-308Lowest double value: -1.7976931348623157e+308Note the differences between min() and lowest(). For an integer, the minimum value equals the lowest value. However, for floating-point types, the minimum value is the smallest positive value that can be represented, while the lowest value is the most negative value representable, which equals -max().

Zero Initialization

Section titled “Zero Initialization”Variables can be initialized to zero with {0}, or with a zero initializer, {}. Zero initialization initializes primitive integer types (such as char, int, and so on) to zero, primitive floating-point types to 0.0, pointer types to nullptr, and constructs objects with the default constructor (discussed later).

Here is an example of zero initializing a float and an int:

float myFloat {};int myInt {};Casting

Section titled “Casting”Variables can be converted to other types by casting them. For example, a float can be cast to an int. C++ provides three ways to explicitly change the type of a variable. The first method is a holdover from C; it is not recommended but, unfortunately, still commonly used. The second method is rarely used. The third method is the most verbose but is also the cleanest one and is therefore recommended.

float myFloat { 3.14f };int i1 { (int)myFloat }; // method 1int i2 { int(myFloat) }; // method 2int i3 { static_cast<int>(myFloat) }; // method 3The resulting integer will be the value of the floating-point number with the fractional part truncated. Chapter 10, “Discovering Inheritance Techniques,” describes the different casting methods in more detail. In some contexts, variables can be automatically cast, or coerced. For example, a short can be automatically converted into a long because a long represents the same type of data with at least the same precision:

long someLong { someShort }; // no explicit cast neededWhen automatically casting variables, you need to be aware of the potential loss of data. For example, casting a float to an int throws away the fractional part of the number, and the resulting integer can even be completely wrong if the floating-point value represents a number bigger than the maximum representable integer value. Most compilers will issue a warning or even an error if you assign a float to an int without an explicit cast. If you are certain that the left-hand side type is fully compatible with the right-hand side type, it’s OK to cast implicitly.

Floating-Point Numbers

Section titled “Floating-Point Numbers”Working with floating-point numbers can be more complicated than working with integral types. You need to keep a few things in mind. Calculations with floating-point values that are orders of magnitude different can cause errors. Furthermore, calculating the difference between two floating-point numbers that are almost identical will cause the loss of precision. Also keep in mind that a lot of decimal values cannot be represented exactly as floating-point numbers. However, going deeper in on the numerical problems with using floating-point numbers and how to write numerical stable floating-point algorithms is outside the scope of this book, as these topics warrant a whole book on their own.

There are several special floating-point numbers:

- +/-infinity: Represents positive and negative infinity, for example the result of dividing a non-zero number by zero

- NaN: Abbreviation for not-a-number, for example the result of dividing zero by zero, a mathematically undefined result

To check whether a given floating-point number is not-a-number, use std::isnan(). To check for infinity, use std::isinf(). Both functions are defined in <cmath>.

To obtain one of these special floating-point values, use numeric_limits, for example std::numeric_limits<double>::infinity().

Section titled “ Extended Floating-Point Types”As mentioned in the section on variables earlier, C++ provides the following standard floating-point types: float, double, and long double.

C++23 introduces the following extended floating-point types that have become popular in certain domains. Support for these is optional, and not all compilers provide these types.

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION | LITERAL SUFFIX |

|---|---|---|

std::float16_t | 16-bit format from the IEEE 754 standard. | F16 or f16 |

std::float32_t | 32-bit format from the IEEE 754 standard. | F32 or f32 |

std::float64_t | 64-bit format from the IEEE 754 standard. | F64 or f64 |

std::float128_t | 128-bit format from the IEEE 754 standard. | F128 or f128 |

std::bfloat16_t | Brain floating point.1 Used in certain AI domains. | BF16 or bf16 |

Most of the time, the standard types, float, double, and long double, are enough. From these, double should be your default type. Using float can trigger loss of precision, and, depending on your use case, this might or might not be acceptable.

Range and Accuracy of Floating-Point Types

Section titled “Range and Accuracy of Floating-Point Types”Floating-point types have a limited range and a limited precision. The following table gives detailed specifications of all standard and extended floating-point types supported by C++. However, the specifications of the standard types, float, double, and long double, are not specified exactly by the C++ standard. The standard says only that long double should have at least the same precision as double, and double should have at least the same precision as float. For these three types, the table shows values commonly used by compilers.

| TYPE | NAME | MANTISSA BITS | DECIMAL DIGITS | EXPONENT BITS | MIN | MAX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

float | Single precision | 24 | 7.22 | 8 | 1.18x10-38 | 3.40x1038 |

double | Double precision | 53 | 15.95 | 11 | 2.23x10-308 | 1.80x10308 |

long double | Extended precision | 64 | 19.27 | 15 | 3.36x10−4932 | 1.19x104932 |

std::float16_t | Half precision | 11 | 3.31 | 5 | 6.10x10-5 | 65504 |

std::float32_t | Single precision | 24 | 7.22 | 8 | 1.18x10-38 | 3.40x1038 |

std::float64_t | Double precision | 53 | 15.95 | 11 | 2.23x10-308 | 1.80x10308 |

std::float128_t | Quadruple precision | 113 | 34.02 | 15 | 3.36x10−4932 | 1.19x104932 |

std::bfloat16_t | Brain floating point | 8 | 2.41 | 8 | 1.18x10-38 | 3.40x1038 |

Operators

Section titled “Operators”What good is a variable if you don’t have a way to change it? The following table shows common operators used in C++ and sample code that makes use of them. Operators in C++ can be binary (operate on two expressions), unary (operate on a single expression), or even ternary (operate on three expressions). There is only one ternary operator in C++, and it is explained in the section “The Conditional Operator” later in this chapter. Furthermore, Chapter 15, “Overloading C++ Operators,” is reserved for operators and explains how you can add support for these operators to your own custom types.

| OPERATOR | DESCRIPTION | USAGE |

|---|---|---|

= | Binary operator to assign the value on the right to the expression on the left. | cpp int i; i = 3; int j; j = i; |

! | Unary operator to complement the true/false (non-0/0) status of an expression. | cpp bool b {!true}; bool b2 {!b}; |

+ | Binary operator for addition. | cpp int i {3 + 2}; int j {i + 5}; int k {i + j}; |

- * / | Binary operators for subtraction, multiplication, and division. | cpp int i {5 – 1}; int j {5 * 2}; int k {j / i}; |

% | Binary operator for the remainder of a division operation. This is also referred to as the mod or modulo operator. For example: 5%2=1. | cpp int rem {5 % 2}; |

++ | Unary operator to increment an expression by 1. If the operator occurs after the expression, or post-increment, the result of the expression is the unincremented value. If the operator occurs before the expression, or pre-increment, the result of the expression is the new value. | cpp i++; ++i; |

-- | Unary operator to decrement an expression by 1. | cpp i--; --i; |

+= -= *= /= %= | Shorthand syntax for: cpp i = i + (j); i = i - (j); i = i * (j); i = i / (j); i = i % (j); | cpp i += j; i -= j; i *= j; i /= j; i %= j; |

& &= | Takes the raw bits of one expression and performs a bitwise AND with the other expression. | cpp i = j & k; j &= k; |

| ` | =` | |

<< >> <<= >>= | Takes the raw bits of an expression and “shifts” each bit left (<<) or right (>>) the specified number of places. | cpp i = i << 1; i = i >> 4; i <<= 1; i>>= 4; |

^ ^= | Performs a bitwise exclusive or, also called XOR operation, on two expressions. | cpp i = i ^ j; i ^= j; |

Operators of the form op=, e.g., +=, are called compound assignment operators.

When a binary operator is applied to two operands of different types, the compiler inserts an implicit conversion to convert one of them to the other before applying the operator. You can also use explicit conversions to convert one type to another using static_cast().

For implicit conversions, the compiler has certain rules to decide which type it converts to which other type. For example, for a binary operation with a small integer type and a larger integer type, the smaller type will be converted to the larger one. However, the results might not always be as you would expect. Thus, I recommend being careful with implicit conversions and using explicit conversions to make sure the compiler does what you intend.

The following code snippet shows the most common variable types and operators in action. It also shows explicit conversions and explains why they are necessary. If you are unsure about how variables and operators work, try to figure out what the output of this program will be, and then run it to confirm your answer.

int someInteger { 256 };short someShort;long someLong;float someFloat;double someDouble;

someInteger++;someInteger *= 2;// Conversion from larger integer type to smaller integer type// can cause a warning or error, hence static_cast() is required.someShort = static_cast<short>(someInteger);someLong = someShort * 10000;someFloat = someLong + 0.785f;// To make sure the division is performed with double precision,// someFloat is explicitly converted to double first.someDouble = static_cast<double>(someFloat) / 100000;println("{}", someDouble);The C++ compiler has a recipe for the order in which expressions are evaluated. If you have a complicated expression with many operators, the order of execution may not be obvious. For that reason, it’s probably better to break up a complicated expression into several smaller expressions, or explicitly group subexpressions by using parentheses. For example, the following line of code might be confusing unless you happen to know the exact evaluation order of the operators:

int i { 34 + 8 * 2 + 21 / 7 % 2 };Adding parentheses makes it clear which operations are happening first:

int i { 34 + (8 * 2) + ( (21 / 7) % 2 ) };For those of you playing along at home, both approaches are equivalent and end up with i equal to 51. If you assumed that C++ evaluated expressions from left to right, your answer would have been 1. C++ evaluates /, *, and % first (in left-to-right order), followed by addition and subtraction, then bitwise operators. Parentheses let you explicitly tell the compiler that a certain operation should be evaluated first.

Formally, the evaluation order of operators is expressed by their precedence. Operators with a higher precedence are executed before operators with a lower precedence. The following list shows the precedence of the operators from the previous table. Operators higher in the list have higher precedence and hence are executed before operators lower in the list.

++ −−(postfix)! ++ −−(prefix)* / %+ −<< >>&^|= += -= *= /= %= &= |= ^= <<= >>=

This is only a selection of the available C++ operators. Chapter 15 gives a complete overview of all available operators, including their precedence.

Enumerations

Section titled “Enumerations”An integer really represents a single value from a larger set of values—the entire sequence of integral numbers. Enumerations are types that let you define your own sequences so that you can declare variables with values in that sequence. For example, in a chess program, you could represent each piece as an int, with constants for the piece types, as shown in the following code. The integers representing the types are marked const to indicate that they can never change.

const int PieceTypeKing { 0 };const int PieceTypeQueen { 1 };const int PieceTypeRook { 2 };const int PieceTypePawn { 3 };//etc.int myPiece { PieceTypeKing };This representation can become dangerous. Since a piece is just an int, what would happen if another programmer added code to increment the value of a piece? By adding 1, a king becomes a queen, which really makes no sense. Worse still, someone could come in and give a piece a value of -1, which has no corresponding constant.

Strongly typed enumerations solve these problems by tightly defining the range of values for a variable. The following code declares a new type, PieceType, which has four possible values, called enumerators, representing four of the chess pieces:

enum class PieceType { King, Queen, Rook, Pawn };This new type can be used as follows:

PieceType piece { PieceType::King };Behind the scenes, an enumeration is just an integer value. The underlying values for King, Queen, Rook, and Pawn are 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. It’s possible to specify the integer values for enumerators yourself. The syntax is as follows:

enum class PieceType{ King = 1, Queen, Rook = 10, Pawn};If you do not assign a value to an enumerator, the compiler automatically assigns it a value that is the previous enumerator incremented by 1. If you do not assign a value to the first enumerator, the compiler assigns it the value 0. So, in this example, King has the integer value 1, Queen has the value 2 assigned by the compiler, Rook has the value 10, and Pawn has the value 11 assigned automatically by the compiler.

Even though enumerators are internally represented by integer values, they are not automatically converted to integers, which means the following is illegal:

int underlyingValue { piece };std::to_underlying(). For example:

int underlyingValue { to_underlying(piece) };By default, the underlying type of an enumerator is an integer, but this can be changed as follows:

enum class PieceType : unsigned long{ King = 1, Queen, Rook = 10, Pawn};For an enum class, the enumerator names are not automatically exported to the enclosing scope. This means they cannot clash with other names already defined in the parent scope. As a result, different strongly typed enumerations can have enumerators with the same name. For example, the following two enumerations are perfectly legal:

enum class State { Unknown, Started, Finished };enum class Error { None, BadInput, DiskFull, Unknown };A big benefit of this is that you can give short names to the enumerators, for example, Unknown instead of UnknownState and UnknownError. However, it also means that you either have to fully qualify enumerators, or use a using enum or using declaration. Here’s an example of a using enum declaration:

using enum PieceType;PieceType piece { King };A using declaration can be used if you want to avoid having to fully qualify specific enumerators. For example, in the following code snippet, King can be used without full qualification, but other enumerators still need to be fully qualified:

using PieceType::King;PieceType piece { King };piece = PieceType::Queen;Even though C++ allows you to avoid fully qualifying enumerators, I recommend using this feature judiciously. At least try to minimize the scope of the using enum or using declaration because if this scope is too big, you risk reintroducing name clashes. The section on the switch statement later in this chapter shows a properly scoped use of a using enum declaration.

Old-Style Enumerations

Section titled “Old-Style Enumerations”New code should always use the strongly typed enumerations explained in the previous section. However, in legacy code bases, you might find old-style enumerations, also known as unscoped enumerations: enum instead of enum class. Here is the previous PieceType defined as an old-style enumeration:

enum PieceType { PieceTypeKing, PieceTypeQueen, PieceTypeRook, PieceTypePawn };The enumerators of such old-style enumerations are exported to the enclosing scope. This means that in the parent scope you can use the names of the enumerators without fully qualifying them, for example:

PieceType myPiece { PieceTypeQueen };This of course also means that they can clash with other names already defined in the parent scope resulting in a compilation error. Here’s an example:

bool ok { false };enum Status { error, ok };This code snippet does not compile because the name ok is first defined to be a Boolean variable, and later the same name is used as the name of an enumerator. Visual C++ 2022 emits the following error:

error C2365: 'ok': redefinition; previous definition was 'data variable'Hence, you should make sure such old-style enumerations have enumerators with unique names, such as PieceTypeQueen, instead of simply Queen.

These old-style enumerations are not strongly typed, meaning they are not type safe. They are always interpreted as integers, and thus you can inadvertently compare enumerators from completely different enumerations, or pass an enumerator of the wrong enumeration to a function.

Always use strongly typed enum class enumerations instead of old-style, unscoped, type-unsafe enum enumerations.

Structs

Section titled “Structs”Structs let you encapsulate one or more existing types into a new type. The classic example of a struct is a database record. If you are building a personnel system to keep track of employee information, you might want to store the first initial, last initial, employee number, and salary for each employee. A struct that contains all of this information is shown in the employee.cppm module interface file that follows. This is your first self-written module in this book. Module interface files usually have .cppm as extension. The first line in the module interface file is a module declaration and states that this file is defining a module called employee. Furthermore, a module needs to explicitly state what it exports, i.e., what will be visible when this module is imported somewhere else. Exporting a type from a module is done with the export keyword in front of, for example, a struct.

export module employee;

export struct Employee { char firstInitial; char lastInitial; int employeeNumber; int salary;};A variable declared with type Employee has all of these fields built in. The individual fields of a struct can be accessed by using the . operator. The example that follows creates and then outputs the record for an employee. Just as with the standard named module std, you don’t use angle brackets when importing custom modules.

import std;import employee; // Import our employee module

using namespace std;

int main(){ // Create and populate an employee. Employee anEmployee; anEmployee.firstInitial = 'J'; anEmployee.lastInitial = 'D'; anEmployee.employeeNumber = 42; anEmployee.salary = 80000; // Output the values of an employee. println("Employee: {}{}", anEmployee.firstInitial, anEmployee.lastInitial); println("Number: {}", anEmployee.employeeNumber); println("Salary: ${}", anEmployee.salary);}Conditional Statements

Section titled “Conditional Statements”Conditional statements let you execute code based on whether something is true. As shown in the following sections, there are two main types of conditional statements in C++: if/else statements and switch statements.

if/else Statements

Section titled “if/else Statements”The most common conditional statement is the if statement, which can be accompanied by an else. If the condition given inside the if statement is true, the line or block of code is executed. If not, execution continues with the else case if present or with the code following the conditional statement. The following code shows a cascading if statement, a fancy way of saying that the if statement has an else statement that in turn has another if statement, and so on:

if (i> 4) { // Do something.} else if (i> 2) { // Do something else.} else { // Do something else.}The expression between the parentheses of an if statement must be a Boolean value or evaluate to a Boolean value. A value of 0 evaluates to false, while any non-zero value evaluates to true. For example, if(0) is equivalent to if(false). Logical evaluation operators, described later, provide ways of evaluating expressions to result in a true or false Boolean value.

Initializers for if Statements

Section titled “Initializers for if Statements”C++ allows you to include an initializer inside an if statement using the following syntax:

if (<initializer>; <conditional_expression>) { <if_body>} else if (<else_if_expression>) { <else_if_body>} else { <else_body>}Any variable introduced in the <initializer> is available only in the <conditional_expression>, in the <if_body>, in all <else_if_expression>s and <else_if_body>s, and in the <else_body>. Such variables are not available outside the if statement.

It is too early in this book to give a useful example of this feature, but here is an example of how it could be employed:

if (Employee employee { getEmployee() }; employee.salary> 1000) { … }In this example, the initializer gets an employee by calling the getEmployee() function. Functions are discussed later in this chapter. The condition checks whether the salary of the retrieved employee exceeds 1000. Only in that case is the body of the if statement executed. More concrete examples will be given throughout this book.

switch Statements

Section titled “switch Statements”The switch statement is an alternate syntax for performing actions based on the value of an expression. In C++, the expression of a switch statement must be of an integral type, a type convertible to an integral type, an enumeration, or a strongly typed enumeration, and must be compared to constants. Each constant value represents a “case.” If the expression matches the case, the subsequent lines of code are executed until a break statement is reached. You can also provide a default case, which is matched if none of the other cases matches. The following pseudocode shows a common use of the switch statement:

switch (menuItem) { case OpenMenuItem: // Code to open a file break; case SaveMenuItem: // Code to save a file break; default: // Code to give an error message break;}A switch statement can always be converted into if/else statements. The previous switch statement can be converted as follows:

if (menuItem == OpenMenuItem) { // Code to open a file} else if (menuItem == SaveMenuItem) { // Code to save a file} else { // Code to give an error message}switch statements are generally used when you want to do something based on more than one specific value of an expression, as opposed to some test on the expression. In such a case, the switch statement avoids cascading if/else statements. If you need to inspect only one value, an if or if/else statement is fine.

Once a case expression matching the switch condition is found, all statements that follow it are executed until a break statement is reached. This execution continues even if another case expression is encountered, which is called fallthrough. In the following example, a single set of statements is executed for both Mode::Standard and Default. If mode is Custom, then value is first changed from 42 to 84, after which the Standard and Default statements are executed. In other words, the Custom case falls through until it eventually reaches a break statement or the end of the switch statement. This code snippet also shows a nice example of using a properly scoped using enum declaration to avoid having to write Mode::Custom, Mode::Standard, and Mode::Default for the different case labels.

enum class Mode { Default, Custom, Standard };

int value { 42 };Mode mode { /* … */ };switch (mode) { using enum Mode;

case Custom: value = 84; case Standard: case Default: // Do something with value … break;}Fallthrough can be a source of bugs, for example if you accidentally forget a break statement. Because of this, some compilers give a warning if a fallthrough is detected in a switch statement, unless the case is empty. In the previous example, no compiler will give a warning that the Standard case falls through to the Default case, but a compiler might give a warning for the Custom case fallthrough. To prevent this warning and to make it clear to a reader and the compiler that the fallthrough is intentional, you can use a [[fallthrough]] attribute as follows:

switch (mode) { using enum Mode;

case Custom: value = 84; [[fallthrough]]; case Standard: case Default: // Do something with value … break;}Surrounding the statements following a case expression with braces is often optional, but sometimes necessary, for example, when defining variables. Here is an example:

switch (mode) { using enum Mode;

case Custom: { int someVariable { 42 }; value = someVariable * 2; [[fallthrough]]; } case Standard: case Default: // Do something with value … break;}When using a switch statement for enumerations, most compilers issue a warning when you don’t handle all different enumerators, either by explicitly writing cases for each enumerator or by writing cases for only a selection of the enumerators in combination with a default case. However, it’s recommended not to include a default case in a switch statement switching on enumerations. Instead, you should explicitly list all enumerators. The reason is that this makes the code less error prone for when you later add more enumerators to the enumeration. In that case, if you forget to add any new enumerator to specific switch statements, the compiler will issue a warning instead of silently handling the new enumerator using the default case.

Initializers for switch Statements

Section titled “Initializers for switch Statements”Just as for if statements, you can use initializers with switch statements. The syntax is as follows:

switch (<initializer>; <expression>) {<body> }Any variables introduced in the <initializer> are available only in the <expression> and in the <body>. They are not available outside the switch statement.

The Conditional Operator

Section titled “The Conditional Operator”C++ has one operator that takes three arguments, known as a ternary operator. It is used as a shorthand conditional expression of the form “if [something] then [perform action], otherwise [perform some other action].” The conditional operator is represented by a ? and a :. The following code outputs “yes” if the variable i is greater than 2, and “no” otherwise:

println("{}", (i> 2) ? "yes" : "no");The parentheses around i > 2 are optional, so the following is equivalent:

println("{}", i> 2 ? "yes" : "no");The advantage of the conditional operator is that it is an expression, not a statement like the if and switch statements. Hence, a conditional operator can occur within almost any context. In the preceding example, the conditional operator is used within code that performs output. A convenient way to remember how the syntax is used is to treat the question mark as though the statement that comes before it really is a question. For example, “Is i greater than 2? If so, the result is ‘yes’; if not, the result is ‘no.’”

Logical Evaluation Operators

Section titled “Logical Evaluation Operators”You have already seen a logical evaluation operator without a formal definition. The > operator compares two values. The result is true if the value on the left is greater than the value on the right. All logical evaluation operators follow this pattern—they all result in a true or false.

The following table shows common logical evaluation operators:

| OP | DESCRIPTION | USAGE |

|---|---|---|

< <= > >= | Determines if the left-hand side is less than, less than or equal to, greater than, or greater than or equal to the right-hand side. | cpp if (i < 0) { print("i is negative"); } |

== | Determines if the left-hand side equals the right-hand side. Don’t confuse this with the = (assignment) operator! | cpp if (i == 3) { print("i is 3"); } |

!= | Not equals. The result of the statement is true if the left-hand side does not equal the right-hand side. | cpp if (i != 3) { print("i is not 3"); } |

<=> | Three-way comparison operator, also called the spaceship operator. Explained in more detail in the next section. | cpp result = i <=> 0; |

! | Logical NOT. This complements the true/``false status of a Boolean expression. This is a unary operator. | cpp if (!bool1) { print("bool1 is false"); } |

&& | Logical AND. The result is true if both parts of the expression are true. | cpp if (bool1 && bool2) { print("both are true"); } |

| ` | ` |

C++ uses short-circuit logic when evaluating logical expressions. That means that once the final result is certain, the rest of the expression won’t be evaluated. For example, if you are performing logical OR operations of several Boolean expressions, as shown in the following code, the result is known to be true as soon as one of them is found to be true. The rest won’t even be checked.

bool result { bool1 || bool2 || (i> 7) || (27 / 13 % i + 1) < 2 };In this example, if bool1 is found to be true, the entire expression must be true, so the other parts aren’t evaluated. In this way, the language saves your code from doing unnecessary work. It can, however, be a source of hard-to-find bugs if the later subexpressions in some way influence the state of the program (for example, by calling a separate function).

The following code shows a statement using && that short-circuits after the second term because 0 always evaluates to false:

bool result { bool1 && 0 && (i> 7) && !done };Short-circuiting can be beneficial for performance. You can put less resource intensive tests first so that more expensive tests are not even executed when the logic short-circuits. It is also useful in the context of pointers to avoid parts of the expression to be executed when a pointer is not valid. Pointers and short-circuiting with pointers are discussed later in this chapter.

Three-Way Comparisons

Section titled “Three-Way Comparisons”The three-way comparison operator can be used to determine the order of two values. It is also called the spaceship operator because its sign, <=>, resembles a spaceship. With a single expression, it tells you whether a value is equal, less than, or greater than another value. Because it has to return more than just true or false, it cannot return a Boolean type. Instead, it returns an enumeration-like type, defined in <compare> in the std namespace. If the operands are integral types, the result is a strong ordering and can be one of the following:

strong_ordering::less: First operand less than secondstrong_ordering::greater: First operand greater than secondstrong_ordering::equal: First operand equal to second

Here is an example of its use:

int i { 11 };strong_ordering result { i <=> 0 };if (result == strong_ordering::less) { println("less"); }if (result == strong_ordering::greater) { println("greater"); }if (result == strong_ordering::equal) { println("equal"); }Certain types don’t have a total ordering. For example, not-a-number floating-point values are never equal, less than, or greater than any other floating-point value. Thus, such comparisons result in a partial ordering:

partial_ordering::less: First operand less than secondpartial_ordering::greater:First operand greater than secondpartial_ordering::equivalent:First operand equivalent to second, meaning!(a<b) && !(b<a); for example, -0.0 is equivalent to +0.0, but they are not equalpartial_ordering::unordered:If one or both of the operands is not-a-number

If you really need a strong ordering of your floating-point values, e.g., if you know they are never not-a-number, you can use std::strong_order(), which always produces an std::strong_ordering result.

There is also a weak ordering, which is an additional ordering type that you can choose from to implement three-way comparisons for your own types. With a weak ordering, all values are ordered, i.e., there is no unordered result, but the ordering is not strong, meaning there can be non-equal values that are equivalent. An example is ordering strings with case-insensitive comparisons. In that case, the strings “Hello World” and “hello world” are certainly not equal, but they are equivalent. Here are the different results of a weak ordering:

weak_ordering::less:First operand less than secondweak_ordering::greater:First operand greater than secondweak_ordering::equivalent:First operand equivalent to second

The three different types of ordering support certain implicit conversions. A strong_ordering can be converted implicitly to a partial_ordering or a weak_ordering. A weak_ordering can be converted implicitly to a partial_ordering.

For primitive types, using the three-way comparison operator doesn’t gain you much compared to just performing individual comparisons using the ==, <, and > operators. However, it becomes useful with objects that are more expensive to compare. With the three-way comparison operator, such objects can be ordered with a single operator, instead of potentially having to call two individual comparison operators, triggering two expensive comparisons. Chapter 9, “Mastering Classes and Objects,” explains how to add support for three-way comparisons to your own types.

Finally, <compare> provides named comparison functions to interpret the result of an ordering. These functions are std::is_eq(), is_neq(), is_lt(), is_lteq(), is_gt(), and is_gteq() returning true if an ordering represents ==, !=, <, <=, >, or >= respectively, false otherwise. Here is an example:

int i { 11 };strong_ordering result { i <=> 0 };if (is_lt(result)) { println("less"); }if (is_gt(result)) { println("greater"); }if (is_eq(result)) { println("equal"); }Functions

Section titled “Functions”For programs of any significant size, placing all the code inside of main() is unmanageable. To make programs easier to understand, you need to break up, or decompose, code into concise functions.

In C++, you first declare a function to make it available for other code to use. If the function is used only inside a particular file, you generally declare and define the function in that source file. If the function is for use by other modules or files, you export a declaration for the function from a module interface file, while the function’s definition can be either in the same module interface file or in a module implementation file (discussed later).

A function declaration is shown in the following code. This example has a return type of void, indicating that the function does not provide a result to the caller. The caller must provide two arguments for the function to work with—an integer and a character.

void myFunction(int i, char c);Without an actual definition to match this function declaration, the link stage of the compilation process will fail because code that makes use of the function will be calling nonexistent code. The following definition prints the values of the two parameters:

void myFunction(int i, char c){ println("The value of i is {}.", i); println("The value of c is {}.", c);}Elsewhere in the program, you can make calls to myFunction() and pass in arguments for the two parameters. Some sample function calls are shown here:

int someInt { 6 };char someChar { 'c' };myFunction(8, 'a');myFunction(someInt, 'b');myFunction(5, someChar);C++ functions can also return a value to the caller. The following function adds two numbers and returns the result:

int addNumbers(int number1, int number2){ return number1 + number2;}This function can be called as follows:

int sum { addNumbers(5, 3) };Function Return Type Deduction

Section titled “Function Return Type Deduction”You can ask the compiler to figure out the return type of a function automatically. To make use of this functionality, just specify auto as the return type.

auto addNumbers(int number1, int number2){ return number1 + number2;}The compiler deduces the return type based on the expressions used for the return statements in the body of the function. There can be multiple return statements, but they must all resolve to exactly the same type as the compiler will never insert any implicit conversions to deduce the return type of a function. Such a function can even include recursive calls (calls to itself), but the first return statement in the function must be a non-recursive call.

Current Function’s Name

Section titled “Current Function’s Name”Every function has a local predefined variable __func__ containing the name of the current function. One use of this variable could be for logging purposes.

int addNumbers(int number1, int number2){ println("Entering function {}", __func__); return number1 + number2;}Function Overloading

Section titled “Function Overloading”Overloading a function means providing several functions with the same name but with a different set of parameters. Only specifying different return types is not enough, as the returned value can be ignored when calling the function; instead, the number and/or types of the parameters must be different.

Suppose you want to provide versions of addNumbers() that work with integers and with doubles. Without overloading, you would have to come up with unique names, for example:

int addNumbersInts(int a, int b) { return a + b; }double addNumbersDoubles(double a, double b) { return a + b; }With function overloading, you don’t need to come up with different names for the different versions of a function. The following code snippet defines two functions called addNumbers(), one defined for integers, the other defined for doubles:

int addNumbers(int a, int b) { return a + b; }double addNumbers(double a, double b) { return a + b; }When calling addNumbers(), the compiler automatically selects the correct function overload based on the provided arguments. This process is called overload resolution.

println("{}", addNumbers(1, 2)); // Calls the integer versionprintln("{}", addNumbers(1.11, 2.22)); // Calls the double versionAttributes

Section titled “Attributes”Attributes are a mechanism to add optional and/or vendor-specific information into source code. Before attributes were standardized in C++, vendors decided how to specify such information. Examples are __attribute__, __declspec, and so on. Since C++11, there is standardized support for attributes by using the double square brackets syntax [[attribute]].

Earlier in this chapter, the [[fallthrough]] attribute is introduced to prevent a compiler warning when fallthrough in a switch case statement is intentional. The C++ standard defines a couple more standard attributes.

[[nodiscard]]

Section titled “[[nodiscard]]”The [[nodiscard]] attribute can be used on a function that returns a value. The compiler will then issue a warning if the return value from that function is not used by the calling function. Here is an example:

[[nodiscard]] int func() { return 42; }

int main(){ func();}The compiler issues a warning similar to the following:

warning C4834: discarding return value of function with 'nodiscard' attributeThis feature can, for example, be used for functions that return error codes. By adding the [[nodiscard]] attribute to such functions, the error codes returned from them cannot be ignored.

More general, the [[nodiscard]] attribute can be used on classes, structs, functions, and enumerations. An example of applying the attribute to an entire class is when you have a class representing error conditions. By applying [[nodiscard]] to such a class, the compiler will issue a warning for every function call that returns such an error condition and where the caller doesn’t do anything with it.

A reason can be provided for the [[nodiscard]] attribute in the form of a string. This reason is then displayed in the warning messages generated by the compiler if the returned value is ignored by the caller of the function. Here is an example:

[[nodiscard("Some explanation")]] int func();[[maybe_unused]]

Section titled “[[maybe_unused]]”The [[maybe_unused]] attribute can be used to suppress the compiler from issuing a warning when something is unused, as in this example:

int func(int param1, int param2){ return 42;}If the compiler warning level is set high enough, this function definition results in two compiler warnings. For example, Microsoft Visual C++ gives these warnings:

warning C4100: 'param2': unreferenced formal parameterwarning C4100: 'param1': unreferenced formal parameterBy using the [[maybe_unused]] attribute, you can suppress such warnings:

int func(int param1, [[maybe_unused]] int param2){ return 42;}In this case, the second parameter is marked with the attribute suppressing its warning. The compiler now only issues a warning for param1:

warning C4100: 'param1': unreferenced formal parameterThe [[maybe_unused]] attribute can be used on classes, structs, non-static data members, unions, typedefs, type aliases, variables, functions, enumerations, and enumerators. Some of these terms you might not know yet but are discussed later in this book.

[[noreturn]]

Section titled “[[noreturn]]”Adding a [[noreturn]] attribute to a function means that it never returns control to the caller. Typically, the function either causes some kind of termination (process termination or thread termination) or throws an exception. Exceptions are discussed later in this chapter. With this attribute, the compiler can avoid giving certain warnings or errors because it now knows more about the intent of the function. Here is an example:

import std;using namespace std;

[[noreturn]] void forceProgramTermination(){ exit(1); // Defined in <cstdlib>}

bool isDongleAvailable(){ bool isAvailable { false }; // Check whether a licensing dongle is available… return isAvailable;}

bool isFeatureLicensed(int featureId){ if (!isDongleAvailable()) { // No licensing dongle found, abort program execution! forceProgramTermination(); } else { // Dongle available, perform license check of the given feature… bool isLicensed { featureId == 42 }; return isLicensed; }}

int main(){ bool isLicensed { isFeatureLicensed(42) }; println("{}", isLicensed);}This code snippet compiles fine without any warnings or errors. However, if you remove the [[noreturn]] attribute, the compiler generates the following warning (output from Visual C++):

warning C4715: 'isFeatureLicensed': not all control paths return a value[[deprecated]]

Section titled “[[deprecated]]”[[deprecated]] can be used to mark something as deprecated, which means you can still use it, but its use is discouraged. This attribute accepts an optional argument that can be used to explain the reason for the deprecation, as in this example:

[[deprecated("Unsafe function, please use xyz")]] void func();If you use this deprecated function, you’ll get a compilation error or warning. For example, GCC gives the following warning:

warning: 'void func()' is deprecated: Unsafe function, please use xyz[[likely]] and [[unlikely]]

Section titled “[[likely]] and [[unlikely]]”The likelihood attributes [[likely]] and [[unlikely]] can be used to help the compiler in optimizing code. These attributes can, for example, be used to mark branches of if and switch statements according to how likely it is that a branch will be taken. However, these attributes are rarely required. Compilers and hardware these days have powerful branch prediction to figure it out themselves, but in certain cases, such as performance critical code, you might have to help the compiler. The syntax is as follows:

int value { /* … */ };if (value> 11) [[unlikely]] { /* Do something … */ }else { /* Do something else … */ }

switch (value){ [[likely]] case 1: // Do something … break; case 2: // Do something … break; [[unlikely]] case 12: // Do something … break;}

Section titled “ [[assume]]”The [[assume]] attribute allows the compiler to assume that certain expressions are true without evaluating them at run time. The compiler can use such assumptions to better optimize the code. As an example, let’s look at the following function:

int divideBy32(int x){ return x / 32;}The function accepts a signed integer, so the compiler has to produce code to make sure the division works for both positive and negative numbers. If you are sure that x will never be negative, and for some reason you cannot make x of type unsigned, you can add an assumption as follows:

int divideBy32(int x){ [[assume(x >= 0)]]; return x / 32;}With this assumption in place, the compiler can omit any code to handle negative numbers and optimize the division into a single instruction, a simple right shift of five bits.

C-Style Arrays

Section titled “C-Style Arrays”This section briefly explains C-style arrays, as you will encounter them in legacy code. However, in C++, it is best to avoid C-style arrays and instead use Standard Library functionality, such as std::array and vector, discussed in the following two sections.

Arrays hold a series of values, all of the same type, each of which can be accessed by its position in the array. In C++, you must provide the size of the array when the array is declared. You cannot give a variable as the size—it must be a constant, or a constant expression (constexpr). Constant expressions are discussed in Chapter 9. The code that follows shows the declaration of an array of three integers followed by three lines to initialize the elements to 0:

int myArray[3];myArray[0] = 0;myArray[1] = 0;myArray[2] = 0;In C++, the first element of an array is always at position 0, not position 1! The last position of the array is always the size of the array minus 1!

The “Loops” section later in this chapter discusses how you could use loops to initialize each element of an array. However, instead of using loops or the previous initialization mechanism, you can also accomplish zero initialization with the following one-liner:

int myArray[3] = { 0 };You can even drop the 0.

int myArray[3] = {};Finally, the equal sign is optional as well, so you can write this:

int myArray[3] {};An array can be initialized with an initializer list, in which case the compiler deduces the size of the array automatically. Here’s an example:

int myArray[] { 1, 2, 3, 4 }; // The compiler creates an array of 4 elements.If you do specify the size of the array and the initializer list has fewer elements than the given size, the remaining elements are set to 0. For example, the following code sets only the first element in the array to the value 2 and sets all others to 0:

int myArray[3] { 2 };To get the size of a stack-based C-style array, you can use the std::size() function, defined in <array>. It returns an std::size_t, which is an unsigned integer type defined in <cstddef>. Here is an example:

std::size_t arraySize { std::size(myArray) };An older trick to get the size of a stack-based C-style array was to use the sizeof operator. The sizeof operator returns the size of its argument in bytes. To get the number of elements in a stack-based array, you divide the size in bytes of the array by the size in bytes of the first element. Here’s an example:

std::size_t arraySize { sizeof(myArray) / sizeof(myArray[0]) };The preceding examples show a one-dimensional array of integers, which you can think of as a line of integers, each with its own numbered compartment. C++ allows multidimensional arrays. You might think of a two-dimensional array as a checkerboard, where each location has a position along the x-axis and a position along the y-axis. Three-dimensional arrays can be pictured as a cube, while higher-dimensional arrays are harder to visualize. The following code shows the syntax for creating a two-dimensional array of characters for a tic-tac-toe board and then putting an “o” in the center square:

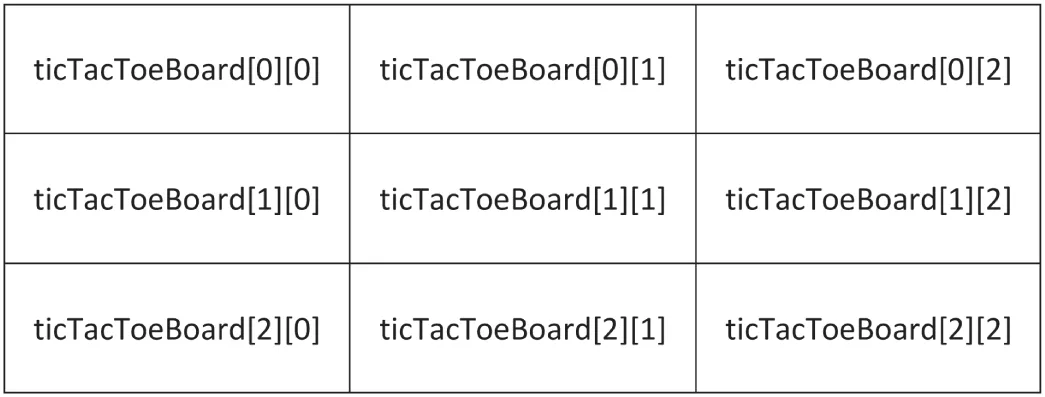

char ticTacToeBoard[3][3];ticTacToeBoard[1][1] = 'o';Figure 1.1 shows a visual representation of this board with the position of each square.

std::array

Section titled “std::array”The arrays discussed in the previous section come from C and still work in C++. However, C++ has a special type for fixed-size containers called std::array, defined in <array>. It’s basically a thin wrapper around C-style arrays.

[^FIGURE 1.1]

There are a number of advantages to using std::arrays instead of C-style arrays. They always know their own size, are not automatically cast to a pointer to avoid certain types of bugs, and have iterators to easily loop over the elements. Iterators are discussed in detail in Chapter 17, “Understanding Iterators and the Ranges Library.”

The following example demonstrates how to use the array container. The array type is a class template accepting a number of class template parameters that allow you to specify how many elements you want to store in the container and their type. You provide class template arguments for class template parameters by specifying them between the angle brackets after array, as in array<int,3>. Chapter 12, “Writing Generic Code with Templates,” discusses templates in detail. However, for now, just remember that you have to specify two arguments between the angle brackets; the first represents the type of the elements in the array, and the second represents the size of the array.

array<int, 3> arr { 9, 8, 7 };println("Array size = {}", arr.size());println("2nd element = {}", arr[1]);C++ supports class template argument deduction (CTAD), as discussed in detail in Chapter 12. For now, it’s enough to remember that this allows you to avoid having to specify the template arguments between angle brackets for certain class templates. CTAD works only when using an initializer because the compiler uses this initializer to automatically deduce the template arguments. This works for std::array, allowing you to define the previous array as follows:

array arr { 9, 8, 7 };If you want an array with a dynamic size, it is recommended to use std::vector, as explained in the next section. A vector automatically increases in size when you add new elements to it.

std::vector

Section titled “std::vector”The C++ Standard Library provides a number of different non-fixed-size containers that can be used to store information. std::vector, declared in <vector>, is an example of such a container. The vector class replaces the concept of C-style arrays with a much more flexible and safer mechanism. As a user, you need not worry about memory management, as a vector automatically allocates enough memory to hold its elements. A vector is dynamic, meaning that elements can be added and removed at run time. Chapter 18, “Standard Library Containers,” goes into more detail regarding containers, but the basic use of a vector is straightforward, which is why it’s introduced in the beginning of this book so that it can be used in examples. The following code demonstrates the basic functionality of vector:

// Create a vector of integers.vector<int> myVector { 11, 22 };

// Add some more integers to the vector using push_back().myVector.push_back(33);myVector.push_back(44);

// Access elements.println("1st element: {}", myVector[0]);myVector is declared as vector<int>. The angle brackets are required to specify the template arguments, just as with std::array. A vector is a generic container. It can contain almost any type of object, but all elements in a vector must be of the same type. This type is specified between the angle brackets. Templates are discussed in detail in Chapter 12 and Chapter 26, “Advanced Templates.”

Just as std::array, the vector class template supports CTAD, allowing you to define myVector as follows:

vector myVector { 11, 22 };Again, an initializer is required for CTAD to work. The following is illegal:

vector myVector;To add elements to a vector, you can use the push_back() member function. Individual elements can be accessed using a similar syntax as for arrays, i.e., operator[].

std::pair