Discovering Inheritance Techniques

Without inheritance, classes would simply be data structures with associated behaviors. That alone would be a powerful improvement over procedural languages, but inheritance adds an entirely new dimension. Through inheritance, you can build new classes based on existing ones. In this way, your classes become reusable and extensible components. This chapter teaches you the different ways to leverage the power of inheritance. You will learn about the specific syntax of inheritance as well as sophisticated techniques for making the most of inheritance.

The portion of this chapter relating to polymorphism draws heavily on the spreadsheet example discussed in Chapter 8, “Gaining Proficiency with Classes and Objects,” and Chapter 9, “Mastering Classes and Objects.” This chapter also refers to the object-oriented methodologies described in Chapter 5, “Designing with Classes.” If you have not read that chapter and are unfamiliar with the theories behind inheritance, you should review Chapter 5 before continuing.

BUILDING CLASSES WITH INHERITANCE

Section titled “BUILDING CLASSES WITH INHERITANCE”In Chapter 5, you learned that an is-a relationship recognizes the pattern that real-world objects tend to exist in hierarchies. In programming, that pattern becomes relevant when you need to write a class that builds on, or slightly changes, another class. One way to accomplish this aim is to copy code from one class and paste it into the other. By changing the relevant parts or amending the code, you can achieve the goal of creating a new class that is slightly different from the original. This approach, however, leaves an OOP programmer feeling sullen and highly annoyed for the following reasons:

- A bug fix to the original class will not be reflected in the new class because the two classes contain completely separate code.

- The compiler does not know about any relationship between the two classes, so they are not polymorphic (see Chapter 5)—they are not just different variations on the same thing.

- This approach does not build a true is-a relationship. The new class is similar to the original because it has similar code, not because it really is the same type of object.

- The original code might not be obtainable. It may exist only in a precompiled binary format, so copying and pasting the code might be impossible.

Not surprisingly, C++ provides built-in support for defining a true is-a relationship. The characteristics of C++ is-a relationships are described in the following section.

Extending Classes

Section titled “Extending Classes”When you write a class definition in C++, you can tell the compiler that your class is inheriting from, deriving from, or extending an existing class. By doing so, your class automatically contains the data members and member functions of the original class, which is called the parent class, base class, or superclass. Extending an existing class gives your class (which is now called a child class, derived class, or subclass) the ability to describe only the ways in which it is different from the parent class.

To extend a class in C++, you specify the class you are extending when you write the class definition. To show the syntax for inheritance, two classes are used, Base and Derived. Don’t worry—more interesting examples are coming later. To begin, consider the following definition for the Base class:

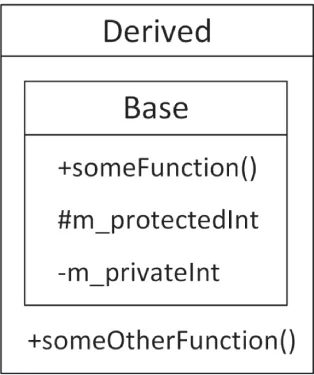

class Base{ public: void someFunction() {} protected: int m_protectedInt { 0 }; private: int m_privateInt { 0 };};If you want to build a new class, called Derived, which inherits from Base, you use the following syntax:

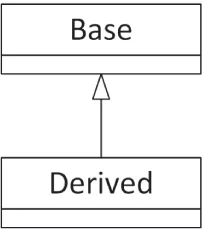

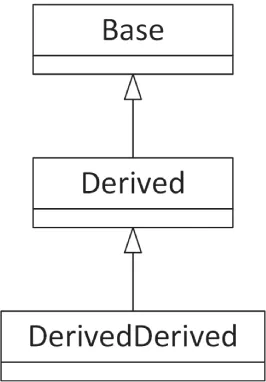

class Derived : public Base{ public: void someOtherFunction() {}};Derived is a full-fledged class that just happens to share the characteristics of the Base class. Don’t worry about the word public for now—its meaning is explained later in this chapter. Figure 10.1 shows the simple relationship between Derived and Base. You can declare objects of type Derived just like any other object. You could even define a third class that inherits from Derived, forming a chain of classes, as shown in Figure 10.2.

[^FIGURE 10.1]

[^FIGURE 10.2]

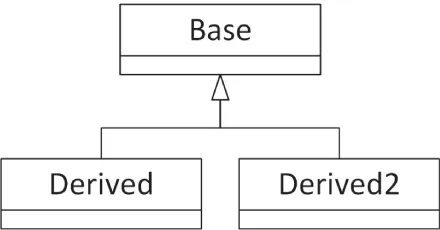

Derived doesn’t have to be the only derived class of Base. Additional classes can also inherit from Base, effectively becoming siblings to Derived, as shown in Figure 10.3.

[^FIGURE 10.3]

Internally, a derived class contains an instance of the base class as a subobject. Graphically this can be represented as in Figure 10.4.

[^FIGURE 10.4]

A Client’s View of Inheritance

Section titled “A Client’s View of Inheritance”To a client, or another part of your code, an object of type Derived is also an object of type Base because Derived inherits from Base. This means that all the public member functions and data members of Base and all the public member functions and data members of Derived are available.

Code that uses the derived class does not need to know which class in your inheritance chain has defined a member function in order to call it. For example, the following code calls two member functions of a Derived object, even though one of the member functions is defined by the Base class:

Derived myDerived;myDerived.someFunction();myDerived.someOtherFunction();It is important to understand that inheritance works in only one direction. The Derived class has a clearly defined relationship to the Base class, but the Base class, as written, doesn’t know anything about the Derived class. That means objects of type Base do not have access to member functions and data members of Derived because Base is not a Derived.

The following code does not compile because the Base class does not contain a public member function called someOtherFunction():

Base myBase;myBase.someOtherFunction(); // Error! Base doesn't have a someOtherFunction().A pointer or reference to a class type can refer to an object of the declared class type or any of its derived classes. This tricky subject is explained in detail later in this chapter. The concept to understand now is that a pointer to Base can actually be pointing to a Derived object. The same is true for a reference. The client can still access only the member functions and data members that exist in Base, but through this mechanism, any code that operates on a Base can also operate on a Derived.

For example, the following code compiles and works just fine, even though it initially appears that there is a type mismatch:

Base* base { new Derived {} }; // Create Derived, store in Base pointer.However, you cannot call member functions from the Derived class through the Base pointer. The following does not work:

base->someOtherFunction();This is flagged as an error by the compiler because, although the object is of type Derived and therefore does have someOtherFunction() defined, the compiler can only think of it as type Base, which does not have someOtherFunction() defined.

A Derived Class’s View of Inheritance

Section titled “A Derived Class’s View of Inheritance”To the derived class, nothing much has changed in terms of how it is written or how it behaves. You can still define member functions and data members on a derived class just as you would on a regular class. The previous definition of Derived declares a member function called someOtherFunction(). Thus, the Derived class augments the Base class by adding an additional member function.

A derived class can access public and protected member functions and data members declared in its base class as though they were its own, because technically they are. For example, the implementation of someOtherFunction() on Derived could make use of the data member m_protectedInt, which is declared as part of Base. The following code shows this. Accessing a base class member is no different than if the member were declared as part of the derived class.

void Derived::someOtherFunction(){ println("I can access base class data member m_protectedInt."); println("Its value is {}", m_protectedInt);}If a class declares members as protected, derived classes have access to them. If they are declared as private, derived classes do not have access. The following implementation of someOtherFunction() does not compile because the derived class attempts to access a private data member from the base class:

void Derived::someOtherFunction(){ println("I can access base class data member m_protectedInt."); println("Its value is {}", m_protectedInt); println("The value of m_privateInt is {}", m_privateInt); // Error!}The private access specifier gives you control over how a potential derived class could interact with your class.

Chapter 4, “Designing Professional C++ Programs,” gives the following rule: all data members should be private; provide public getters and setters if you want to provide access to data members from outside the class. This rule can now be extended to include the protected access specifier.

All data members should be private. Provide public getters and setters if you want to provide access to data members from outside the class and provide protected getters and setters if you want only derived classes to access them.

The reason to make data members private by default is that this provides the highest level of encapsulation. This means that you can change how you represent your data while keeping the public and protected interfaces unchanged. Additionally, without giving direct access to data members, you can easily add checks on the input data in your public and protected setters. Member functions should also be private by default. Only make those member functions public that are designed to be public and make member functions protected if you want only derived classes to have access to them.

The following table summarizes the meaning of all three access specifiers:

| ACCESS SPECIFIER | MEANING | WHEN TO USE |

|---|---|---|

public | Any code can call a public member function or access a public data member of an object. | Behaviors (member functions) that you want clients to use. Access member functions (getters and setters) for private and protected data members. |

protected | Any member function of the class can call protected member functions and access protected data members. Member functions of derived classes can access protected members of a base class. | “Helper” member functions that you do not want clients to use. |

private | Only member functions of the class can call private member functions and access private data members. Member functions in derived classes cannot access private members of a base class. | Everything should be private by default, especially data members. You can provide protected getters and setters if you only want to allow derived classes to access them, and provide public getters and setters if you want clients to access them. |

Preventing Inheritance

Section titled “Preventing Inheritance”C++ allows you to mark a class as final, which means trying to inherit from it will result in a compilation error. A class can be marked as final with the final keyword right behind the name of the class. For example, if a class tries to inherit from the following Foo class, the compiler will produce an error:

class Foo final { };Overriding Member Functions

Section titled “Overriding Member Functions”The main reasons to inherit from a class are to add or replace functionality. The definition of Derived adds functionality to its parent class by providing an additional member function, someOtherFunction(). The other member function, someFunction(), is inherited from Base and behaves in the derived class exactly as it does in the base class. In many cases, you will want to modify the behavior of a class by replacing, or overriding, a member function.

The virtual Keyword

Section titled “The virtual Keyword”Simply defining a member function from a base class in a derived class does not properly override that member function. To correctly override a member function, we need a new C++ keyword called virtual. Only member functions that are declared as virtual in the base class can be overridden properly by derived classes. The keyword goes at the beginning of a member function declaration as shown in the modified version of Base that follows:

class Base{ public: virtual void someFunction(); // Remainder omitted for brevity.};The same holds for the Derived class. Its member functions should also be marked virtual if you want to override them in further derived classes:

class Derived : public Base{ public: virtual void someOtherFunction();};The virtual keyword is not repeated in front of the member function definition, e.g.:

void Base::someFunction(){ println("This is Base's version of someFunction().");}Attempting to override a non-virtual member function from a base class hides the base class definition, and it will be used only in the context of the derived class.

Syntax for Overriding a Member Function

Section titled “Syntax for Overriding a Member Function”To override a member function, you redeclare it in the derived class definition exactly as it was declared in the base class, but you add the override keyword and remove the virtual keyword. For example, if you want to provide a new definition for someFunction() in the Derived class, you must first add it to the class definition for Derived, as follows:

class Derived : public Base{ public: void someFunction() override; // Overrides Base's someFunction() virtual void someOtherFunction();};The new definition of someFunction() is specified along with the rest of Derived’s member functions. Just as with the virtual keyword, you do not repeat the override keyword in the member function definition:

void Derived::someFunction(){ println("This is Derived's version of someFunction().");}If you want, you are allowed to add the virtual keyword in front of overridden member functions, but it’s redundant. Here’s an example:

class Derived : public Base{ public: virtual void someFunction() override; // Overrides Base's someFunction()};Once a member function or destructor is marked as virtual, it is virtual for all derived classes even if the virtual keyword is removed from derived classes.

A Client’s View of Overridden Member Functions

Section titled “A Client’s View of Overridden Member Functions”With the preceding changes, other code still calls someFunction() the same way it did before. Just as before, the member function could be called on an object of class Base or an object of class Derived. Now, however, the behavior of someFunction() varies based on the class of the object.

For example, the following code works just as it did before, calling Base’s version of someFunction():

Base myBase;myBase.someFunction(); // Calls Base's version of someFunction().The output of this code is as follows:

This is Base's version of someFunction().If the code declares an object of class Derived, the other version is automatically called:

Derived myDerived;myDerived.someFunction(); // Calls Derived's version of someFunction()The output this time is as follows:

This is Derived's version of someFunction().Everything else about objects of class Derived remains the same. Other member functions that might have been inherited from Base still have the definition provided by Base unless they are explicitly overridden in Derived.

As you learned earlier, a pointer or reference can refer to an object of a class or any of its derived classes. The object itself “knows” the class of which it is actually a member, so the appropriate member function is called as long as it was declared virtual. For example, if you have a Base reference that refers to an object that is really a Derived, calling someFunction() actually calls the derived class’s version, as shown next. This aspect of overriding does not work properly if you omit the virtual keyword in the base class.

Derived myDerived;Base& ref { myDerived };ref.someFunction(); // Calls Derived's version of someFunction()Remember that even though a Base reference or pointer knows that it is referring to a Derived instance, you cannot access Derived class members that are not defined in Base. The following code does not compile because a Base reference does not have a member function called someOtherFunction():

Derived myDerived;Base& ref { myDerived };myDerived.someOtherFunction(); // This is fine.ref.someOtherFunction(); // ErrorThis derived class knowledge characteristic is not true for nonpointer or nonreference objects. You can cast or assign a Derived to a Base because a Derived is a Base. However, the object loses any knowledge of the Derived class at that point.

Derived myDerived;Base assignedObject { myDerived }; // Assigns a Derived to a Base.assignedObject.someFunction(); // Calls Base's version of someFunction()One way to remember this seemingly strange behavior is to imagine what the objects look like in memory. Picture a Base object as a box taking up a certain amount of memory. A Derived object is a box that is slightly bigger because it has everything a Base has plus a bit more. Whether you have a Derived or Base reference or pointer to a Derived, the box doesn’t change—you just have a new way of accessing it. However, when you cast a Derived into a Base, you are throwing out all the “uniqueness” of the Derived class to fit it into a smaller box.

The override Keyword

Section titled “The override Keyword”The use of the override keyword is optional, but highly recommended. Without the keyword, it is possible to accidentally create a new (virtual) member function in a derived class instead of overriding a member function from the base class, effectively hiding the member function from the base class. Take the following Base and Derived classes where Derived is properly overriding someFunction(), but is not using the override keyword:

class Base{ public: virtual void someFunction(double d);};

class Derived : public Base{ public: virtual void someFunction(double d);};You can call someFunction() through a reference as follows:

Derived myDerived;Base& ref { myDerived };ref.someFunction(1.1); // Calls Derived's version of someFunction()This correctly calls the overridden someFunction() from the Derived class. Now, suppose you accidentally use an integer parameter instead of a double while overriding someFunction(), as follows:

class Derived : public Base{ public: virtual void someFunction(int i);};This code does not override someFunction() from Base, but instead creates a new virtual member function. If you try to call someFunction() through a Base reference as in the following code, someFunction() of Base is called instead of the one from Derived!

Derived myDerived;Base& ref { myDerived };ref.someFunction(1.1); // Calls Base's version of someFunction()This type of problem can happen when you start to modify the Base class but forget to update all derived classes. For example, maybe your first version of the Base class has a member function called someFunction() accepting an integer. You then write the Derived class overriding this someFunction() accepting an integer. Later you decide that someFunction() in Base needs a double instead of an integer, so you update someFunction() in the Base class. It could happen that at that time, you forget to update overrides of someFunction() in derived classes to also accept a double instead of an integer. By forgetting this, you are now actually creating a new virtual member function instead of properly overriding the base member function.

You can prevent this situation by using the override keyword as follows:

class Derived : public Base{ public: void someFunction(int i) override;};This definition of Derived generates a compilation error, because with the override keyword you are saying that someFunction() is supposed to be overriding a member function from a base class, but the Base class has no someFunction() accepting an integer, only one accepting a double.

The problem of accidentally creating a new member function instead of properly overriding one can also happen when you rename a member function in the base class and forget to rename the overriding member functions in derived classes.

Always use the override keyword on member functions that are meant to be overriding member functions from a base class.

The Truth about virtual

Section titled “The Truth about virtual”By now you know that if a member function is not virtual, trying to override it in a derived class will hide the base class’s version of that member function. This section explores how virtual member functions are implemented by the compiler and what their performance impact is, as well as discussing the importance of virtual destructors.

How virtual Is Implemented

Section titled “How virtual Is Implemented”To understand how member function hiding is avoided, you need to know a bit more about what the virtual keyword actually does. When a class is compiled in C++, a binary object is created that contains all member functions for the class. In the non-virtual case, the code to transfer control to the appropriate member function is hard-coded directly where the member function is called based on the compile-time type. This is called static binding, also known as early binding.

If the member function is declared virtual, the correct implementation is called through the use of a special area of memory called the vtable, or “virtual table.” Each class that has one or more virtual member functions has a vtable, and every object of such a class contains a pointer to said vtable. This vtable contains pointers to the implementations of the virtual member functions. In this way, when a member function is called on a pointer or reference to an object, its vtable pointer is followed, and the appropriate version of the member function is executed based on the actual type of the object at run time. This is called dynamic binding, also known as late binding. It’s important to remember that this dynamic binding works only when using pointers or references to objects. If you call a virtual member function directly on an object, then that call will use static binding resolved at compile time.

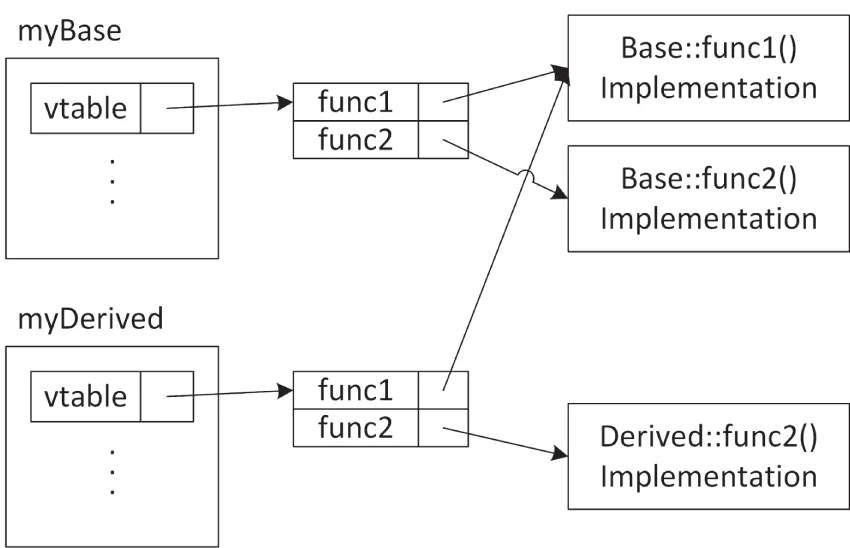

To better understand how vtables make overriding of member functions possible, take the following Base and Derived classes as an example:

class Base{ public: virtual void func1(); virtual void func2(); void nonVirtualFunc();};

class Derived : public Base{ public: void func2() override; void nonVirtualFunc();};For this example, assume that you have the following two instances:

Base myBase;Derived myDerived;Figure 10.5 shows a high-level view of the vtables of both instances. The myBase object contains a pointer to its vtable. This vtable has two entries, one for func1() and one for func2(). Those entries point to the implementations of Base::func1() and Base::func2().

[^FIGURE 10.5]

myDerived also contains a pointer to its vtable, which also has two entries, one for func1() and one for func2(). Its func1() entry points to Base::func1() because Derived does not override func1(). On the other hand, its func2() entry points to Derived::func2().

Note that both vtables do not contain any entry for the nonVirtualFunc() member function because that member function is not virtual.

The Justification for virtual

Section titled “The Justification for virtual”In some languages, such as Java, all member functions are automatically virtual so they can be overridden properly. In C++ that’s not the case. The argument against making everything virtual in C++, and the reason that the keyword was created in the first place, has to do with the overhead of the vtable. To call a virtual member function, the program needs to perform an extra operation by dereferencing the pointer to the appropriate code to execute. This is a miniscule performance hit in most cases, but the designers of C++ thought that it was better, at least at the time, to let the programmer decide if the performance hit was necessary. If the member function was never going to be overridden, there was no need to make it virtual and take the performance hit. However, with today’s CPUs, the performance hit is measured in fractions of a nanosecond, and this will keep getting smaller with future CPUs. In most applications, you will not have a measurable performance difference between using virtual member functions and avoiding them.

Still, in certain specific use cases, the performance overhead might be too costly, and you may need to have an option to avoid the hit. For example, suppose you have a Point class that has a virtual member function. If you have another data structure that stores millions or even billions of Points, calling a virtual member function on each point creates significant overhead. In that case, it’s probably wise to avoid any virtual member functions in your Point class.

There is also a tiny hit to memory usage for each object. In addition to the implementation of the member function, each object also needs a pointer for its vtable, which takes up a tiny amount of space. This is not an issue in the majority of cases. However, sometimes it does matter. Take again the Point class and the container storing billions of Points. In that case, the additional required memory becomes significant.

The Need for virtual Destructors

Section titled “The Need for virtual Destructors”Destructors should almost always be virtual. Making your destructors non-virtual can easily result in situations in which memory is not freed by object destruction. Only for a class that is marked as final could you make its destructor non-virtual.

For example, if a derived class uses memory that is dynamically allocated in the constructor and deleted in the destructor, it will never be freed if the destructor is never called. Similarly, if your derived class has members that are automatically deleted when an instance of the class is destroyed, such as std::unique_ptrs, then those members will not get deleted either if the destructor is never called.

As the following code shows, it is easy to “trick” the compiler into skipping the call to the destructor if it is non-virtual:

class Base{ public: Base() = default; ˜Base() {}};

class Derived : public Base{ public: Derived() { m_string = new char[30]; println("m_string allocated"); }

˜Derived() { delete[] m_string; println("m_string deallocated"); } private: char* m_string;};

int main(){ Base* ptr { new Derived {} }; // m_string is allocated here. delete ptr; // ˜Base is called, but not ˜Derived because the destructor // is not virtual!}As you can see from the following output, the destructor of the Derived object is never called, that is, the “m_string deallocated” message is never displayed:

m_string allocatedTechnically, the behavior of the delete call in the preceding code is undefined by the standard. A C++ compiler could do whatever it wants in such undefined situations. However, most compilers simply call the destructor of the base class, and not the destructor of the derived class.

The fix is to mark the destructor in the base class as virtual. If you don’t need to do any extra work in that destructor but want to make it virtual, you can explicitly default it. Here’s an example:

class Base{ public: Base() = default; virtual ˜Base() = default;};With this change, the output is as expected:

m_string allocatedm_string deallocatedNote that since C++11, the generation of a copy constructor and copy assignment operator is deprecated if the class has a user-declared destructor. Basically, once you have a user-declared destructor, the rule of five kicks in. This means you need to declare a copy constructor, copy assignment operator, move constructor, and move assignment operator, possibly by explicitly defaulting them. This is not done in the examples in this chapter in the interest of keeping them concise and to the point.

Unless you have a specific reason not to, or the class is marked as final, destructors should be marked as virtual. Constructors cannot and need not be virtual because you always specify the exact class being constructed when creating an object.

Earlier in this chapter it was advised to use the override keyword on member functions that are meant to override base class member functions. It’s also possible to use the override keyword on a destructor. This makes sure that the compiler will trigger an error if the destructor in the base class is not virtual. You can combine virtual, override, and default. Here’s an example:

class Derived : public Base{ public: virtual ˜Derived() override = default;};Preventing Overriding

Section titled “Preventing Overriding”Besides marking an entire class as final, C++ also allows you to mark individual member functions as final. Such member functions cannot be overridden in a further derived class. For example, overriding someFunction() from the following Derived class in DerivedDerived results in a compilation error:

class Base{ public: virtual ˜Base() = default; virtual void someFunction();};class Derived : public Base{ public: void someFunction() override final;};class DerivedDerived : public Derived{ public: void someFunction() override; // Compilation error.};INHERITANCE FOR REUSE

Section titled “INHERITANCE FOR REUSE”Now that you are familiar with the basic syntax for inheritance, it’s time to explore one of the main reasons that inheritance is an important feature of the C++ language. Inheritance is a vehicle that allows you to leverage existing code. This section presents an example of inheritance for the purpose of code reuse.

The WeatherPrediction Class

Section titled “The WeatherPrediction Class”Imagine that you are given the task of writing a program to issue simple weather predictions, working with both Fahrenheit and Celsius. Weather predictions may be a little bit out of your area of expertise as a programmer, so you obtain a third-party class library that was written to make weather predictions based on the current temperature and the current distance between Jupiter and Mars (hey, it’s plausible). This third-party package is distributed as a compiled library to protect the intellectual property of the prediction algorithms, but you do get to see the class definition. The weather_prediction module interface file looks as follows:

export module weather_prediction;import std;// Predicts the weather using proven new-age techniques given the current// temperature and the distance from Jupiter to Mars. If these values are// not provided, a guess is still given but it's only 99% accurate.export class WeatherPrediction{ public: // Virtual destructor virtual ˜WeatherPrediction(); // Sets the current temperature in Fahrenheit virtual void setCurrentTempFahrenheit(int temp); // Sets the current distance between Jupiter and Mars virtual void setPositionOfJupiter(int distanceFromMars); // Gets the prediction for tomorrow's temperature virtual int getTomorrowTempFahrenheit() const; // Gets the probability of rain tomorrow. 1 means // definite rain. 0 means no chance of rain. virtual double getChanceOfRain() const; // Displays the result to the user in this format: // Result: x.xx chance. Temp. xx virtual void showResult() const; // Returns a string representation of the temperature virtual std::string getTemperature() const; private: int m_currentTempFahrenheit { 0 }; int m_distanceFromMars { 0 };};Note that this class marks all member functions as virtual, because the class presumes that they might get overridden in derived classes.

This class solves most of the problems for your program. However, as is usually the case, it’s not exactly right for your needs. First, all the temperatures are given in Fahrenheit. Your program needs to operate in Celsius as well. Also, the showResult() member function might not display the result in a way you require.

Adding Functionality in a Derived Class

Section titled “Adding Functionality in a Derived Class”When you learned about inheritance in Chapter 5, adding functionality was the first technique described. Fundamentally, your program needs something just like the WeatherPrediction class but with a few extra bells and whistles. Sounds like a good case for inheritance to reuse code. To begin, define a new class, MyWeatherPrediction, that inherits from WeatherPrediction:

import weather_prediction;

export class MyWeatherPrediction : public WeatherPrediction{};The preceding class definition compiles just fine. The MyWeatherPrediction class can already be used in place of WeatherPrediction. It provides the same functionality, but nothing new yet. For the first modification, you might want to add knowledge of the Celsius scale to the class. There is a bit of a quandary here because you don’t know what the class is doing internally. If all of the internal calculations are made using Fahrenheit, how do you add support for Celsius? One way is to use the derived class to act as a go-between, interfacing between the user, who can use either scale, and the base class, which only understands Fahrenheit.

The first step in supporting Celsius is to add new member functions that allow clients to set the current temperature in Celsius instead of Fahrenheit and to get tomorrow’s prediction in Celsius instead of Fahrenheit. You also need private helper functions that convert between Celsius and Fahrenheit in both directions. These functions can be static because they are the same for all instances of the class.

export class MyWeatherPrediction : public WeatherPrediction{ public: virtual void setCurrentTempCelsius(int temp); virtual int getTomorrowTempCelsius() const; private: static int convertCelsiusToFahrenheit(int celsius); static int convertFahrenheitToCelsius(int fahrenheit);};The new member functions follow the same naming convention as the parent class. Remember that from the point of view of other code, a MyWeatherPrediction object has all of the functionality defined in both MyWeatherPrediction and WeatherPrediction. Adopting the parent class’s naming convention presents a consistent interface.

The implementation of the Celsius/Fahrenheit conversion functions is left as an exercise for the reader—and a fun one at that! The other two member functions are more interesting. To set the current temperature in Celsius, you need to convert the temperature first and then present it to the parent class in units that it understands:

void MyWeatherPrediction::setCurrentTempCelsius(int temp){ int fahrenheitTemp { convertCelsiusToFahrenheit(temp) }; setCurrentTempFahrenheit(fahrenheitTemp);}As you can see, once the temperature is converted, the member function calls the existing functionality from the base class. Similarly, the implementation of getTomorrowTempCelsius() uses the parent’s existing functionality to get the temperature in Fahrenheit, but converts the result before returning it:

int MyWeatherPrediction::getTomorrowTempCelsius() const{ int fahrenheitTemp { getTomorrowTempFahrenheit() }; return convertFahrenheitToCelsius(fahrenheitTemp);}The two new member functions effectively reuse the parent class because they “wrap” the existing functionality in a way that provides a new interface for using it.

You can also add new functionality completely unrelated to existing functionality of the parent class. For example, you could add a member function that retrieves alternative forecasts from the Internet or a member function that suggests an activity based on the predicted weather.

Replacing Functionality in a Derived Class

Section titled “Replacing Functionality in a Derived Class”The other major technique for inheritance is replacing existing functionality. The showResult() member function in the WeatherPrediction class is in dire need of a facelift. MyWeatherPrediction can override this member function to replace the behavior with its own implementation.

The new class definition for MyWeatherPrediction is as follows:

export class MyWeatherPrediction : public WeatherPrediction{ public: virtual void setCurrentTempCelsius(int temp); virtual int getTomorrowTempCelsius() const; void showResult() const override; private: static int convertCelsiusToFahrenheit(int celsius); static int convertFahrenheitToCelsius(int fahrenheit);};Here is a new, user-friendlier implementation of the overridden showResult() member function:

void MyWeatherPrediction::showResult() const{ println("Tomorrow will be {} degrees Celsius ({} degrees Fahrenheit)", getTomorrowTempCelsius(), getTomorrowTempFahrenheit()); println("Chance of rain is {}%", getChanceOfRain() * 100); if (getChanceOfRain()> 0.5) { println("Bring an umbrella!"); }}To clients using this class, it’s as if the old version of showResult() never existed. As long as the object is a MyWeatherPrediction object, the new version is called. As a result of these changes, MyWeatherPrediction has emerged as a new class with new functionality tailored to a more specific purpose. Yet, it did not require much code because it leveraged its base class’s existing functionality.

RESPECT YOUR PARENTS

Section titled “RESPECT YOUR PARENTS”When you write a derived class, you need to be aware of the interaction between parent classes and child classes. Issues such as order of creation, constructor chaining, and casting are all potential sources of bugs.

Parent Constructors

Section titled “Parent Constructors”Objects don’t spring to life all at once; they must be constructed along with their parents and any objects that are contained within them. C++ defines the creation order as follows:

- If the class has a base class, the default constructor of the base class is executed, unless there is a call to a base class constructor in the ctor-initializer, in which case that constructor is called instead of the default constructor.

- Non-

staticdata members of the class are constructed in the order in which they are declared. - The body of the class’s constructor is executed.

These rules can apply recursively. If the class has a grandparent, the grandparent is initialized before the parent, and so on. The following code shows this creation order. The proper execution of this code outputs 123.

class Something{ public: Something() { print("2"); }};

class Base{ public: Base() { print("1"); }};

class Derived : public Base{ public: Derived() { print("3"); } private: Something m_dataMember;};

int main(){ Derived myDerived;}When the myDerived object is created, the constructor for Base is called first, outputting the string "1". Next, m_dataMember is initialized, calling the Something constructor, which outputs the string "2". Finally, the Derived constructor is called, which outputs "3".

Note that the Base constructor is called automatically. C++ automatically calls the default constructor for the parent class if one exists. If no default constructor exists in the parent class or if one does exist but you want to use an alternate parent constructor, you can chain the constructor just as when initializing data members in the ctor-initializer. For example, the following code shows a version of Base that lacks a default constructor. The associated version of Derived must explicitly tell the compiler how to call the Base constructor or the code will not compile.

class Base{ public: explicit Base(int i) {}};

class Derived : public Base{ public: Derived() : Base { 7 } { /* Other Derived's initialization … */ }};The Derived constructor passes a fixed value (7) to the Base constructor. Of course, Derived could also pass a variable:

Derived::Derived(int i) : Base { i } { /* Other Derived's initialization … */ }Passing constructor arguments from the derived class to the base class is perfectly fine and quite normal. Passing data members, however, will not work. The code will compile, but remember that data members are not initialized until after the base class is constructed. If you pass a data member as an argument to the parent constructor, it will be uninitialized.

Parent Destructors

Section titled “Parent Destructors”Because destructors cannot take arguments, the language can always automatically call the destructor for parent classes. The order of destruction is conveniently the reverse of the order of construction:

- The body of the class’s destructor is called.

- Any data members of the class are destroyed in the reverse order of their construction.

- The parent class, if any, is destructed.

Again, these rules apply recursively. The lowest member of the chain is always destructed first. The following code adds destructors to the earlier example. The destructors are all declared virtual! If executed, this code outputs "123321".

class Something{ public: Something() { print("2"); } virtual ˜Something() { print("2"); }};

class Base{ public: Base() { print("1"); } virtual ˜Base() { print("1"); }};

class Derived : public Base{ public: Derived() { print("3"); } virtual ˜Derived() override { print("3"); } private: Something m_dataMember;};If the preceding destructors were not declared virtual, the code would seem to work fine. However, if code ever called delete on a Base pointer that was really pointing to a Derived instance, the destruction chain would begin in the wrong place. For example, if you remove the virtual and override keywords from all destructors in the previous code, then a problem arises when a Derived object is accessed as a pointer to a Base and deleted, as shown here:

Base* ptr { new Derived{} };delete ptr;The output of this code is a shockingly terse "1231". When the ptr variable is deleted, only the Base destructor is called because the destructor was not declared virtual. As a result, the Derived destructor is not called, and the destructors for its data members are not called!

Technically, you could fix the preceding problem by marking only the Base destructor virtual. The “virtualness” automatically applies to any derived classes. However, I advocate explicitly making all destructors virtual so that you never have to worry about it.

Always make your destructors virtual! The compiler-generated default destructor is not virtual, so you should define (or explicitly default) a virtual destructor, at least for your non-final base classes.

virtual Member Function Calls within Constructors and Destructor

Section titled “virtual Member Function Calls within Constructors and Destructor”virtual member functions behave differently in constructors and destructors. If your derived class has overridden a virtual member function from a base class, calling that member function from a base class constructor or destructor calls the base class implementation of that virtual member function and not your overridden version in the derived class! In other words, calls to virtual member functions from within a constructor or destructor are resolved statically at compile time.

The reason for this behavior of constructors has to do with the order of initialization when constructing an instance of a derived class. When creating such an instance, the constructor of any base class is called first, before the derived class instance is fully initialized. Hence, it would be dangerous to already call overridden virtual member functions from the not-yet-fully initialized derived class. A similar reasoning holds for destructors due to the order of destruction when destroying an object.

If you really need polymorphic behavior in your constructors, although this is not recommended, you can define an initialize() virtual member function in your base class, which derived classes can override. Clients creating an instance of your class will have to call this initialize() member function after construction has finished.

Similarly, if you need polymorphic behavior in your destructor, again, not recommended, you can define a shutdown() virtual member function that clients then need to call before the object is destroyed.

Referring to Parent Names

Section titled “Referring to Parent Names”When you override a member function in a derived class, you are effectively replacing the original as far as other code is concerned. However, that parent version of the member function still exists, and you may want to make use of it. For example, an overridden member function would like to keep doing what the base class implementation does, plus something else. Take a look at the getTemperature() member function in the WeatherPrediction class that returns a string representation of the current temperature:

export class WeatherPrediction{ public: virtual std::string getTemperature() const; // Remainder omitted for brevity.};You can override this member function in the MyWeatherPrediction class as follows:

export class MyWeatherPrediction : public WeatherPrediction{ public: std::string getTemperature() const override; // Remainder omitted for brevity.};Suppose the derived class wants to add °F to the string by first calling the base class’s getTemperature() member function and then adding °F to it. You might write this as follows:

string MyWeatherPrediction::getTemperature() const{ // Note: \u00B0 is the ISO/IEC 10646 representation of the degree symbol. return getTemperature() + "\u00B0F"; // BUG}However, this does not work because, under the rules of name resolution for C++, it first resolves against the local scope, then resolves against the class scope, and as a result ends up calling MyWeatherPrediction::getTemperature(). This causes an infinite recursion until you run out of stack space (some compilers detect this error and report it at compile time).

To make this work, you need to use the scope resolution operator as follows:

string MyWeatherPrediction::getTemperature() const{ // Note: \u00B0 is the ISO/IEC 10646 representation of the degree symbol. return WeatherPrediction::getTemperature() + "\u00B0F";}Calling the parent version of the current member function is a commonly used pattern in C++. If you have a chain of derived classes, each might want to perform the operation already defined by the base class but add their own additional functionality as well.

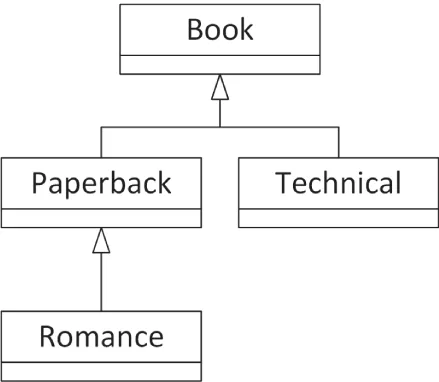

Let’s look at another example. Imagine a class hierarchy of book types, as shown in Figure 10.6.

[^FIGURE 10.6]

Because each lower class in the hierarchy further specifies the type of book, a member function that gets the description of a book really needs to take all levels of the hierarchy into consideration. This can be accomplished by chaining to the parent member function. The following code illustrates this pattern:

class Book{ public: virtual ˜Book() = default; virtual string getDescription() const { return "Book"; } virtual int getHeight() const { return 120; }};

class Paperback : public Book{ public: string getDescription() const override { return "Paperback " + Book::getDescription(); }};

class Romance : public Paperback{ public: string getDescription() const override { return "Romance " + Paperback::getDescription(); } int getHeight() const override { return Paperback::getHeight() / 2; }};

class Technical : public Book{ public: string getDescription() const override { return "Technical " + Book::getDescription(); }};

int main(){ Romance novel; Book book; println("{}", novel.getDescription()); // Outputs "Romance Paperback Book" println("{}", book.getDescription()); // Outputs "Book" println("{}", novel.getHeight()); // Outputs "60" println("{}", book.getHeight()); // Outputs "120"}The Book base class has two virtual member functions: getDescription() and getHeight(). All derived classes override getDescription(), but only the Romance class overrides getHeight() by calling getHeight() on its parent class (Paperback) and dividing the result by two. Paperback does not override getHeight(), but C++ walks up the class hierarchy to find a class that implements getHeight(). In this example, Paperback::getHeight() resolves to Book::getHeight().

Casting Up and Down

Section titled “Casting Up and Down”As you have already seen, an object can be cast or assigned to its parent class. Here’s an example:

Derived myDerived;Base myBase { myDerived }; // Slicing!Slicing occurs in situations like this because the end result is a Base object, and Base objects lack the additional functionality defined in the Derived class. However, slicing does not occur if a derived class is assigned to a pointer or reference to its base class:

Base& myBase { myDerived }; // No slicing!This is generally the correct way to refer to a derived class in terms of its base class, also called upcasting. This is why it’s always a good idea for functions to take references to classes instead of directly using objects of those classes. By using references, derived classes can be passed in without slicing.

When upcasting, use a pointer or reference to the base class to avoid slicing.

Casting from a base class to one of its derived classes, also called downcasting, is often frowned upon by professional C++ programmers because there is no guarantee that the object really belongs to that derived class and because downcasting is a sign of bad design. For example, consider the following code:

void presumptuous(Base* base){ Derived* myDerived { static_cast<Derived*>(base) }; // Proceed to access Derived member functions on myDerived.}If the author of presumptuous() also writes the code that calls presumptuous(), everything will probably be OK, albeit still ugly, because the author knows that the function expects the argument to be of type Derived*. However, if other programmers call presumptuous(), they might pass in a Base*. There are no compile-time checks that can be done to enforce the type of the argument, and the function blindly assumes that base is actually a pointer to a Derived object.

Downcasting is sometimes necessary, and you can use it effectively in controlled circumstances. However, if you are going to downcast, you should use a dynamic_cast(), which uses the object’s built-in knowledge of its type to refuse a cast that doesn’t make sense. This built-in knowledge typically resides in the vtable, which means that dynamic_cast() works only for objects with a vtable, that is, objects with at least one virtual member. If a dynamic_cast() fails on a pointer, the result will be nullptr instead of pointing to nonsensical data. If a dynamic_cast() fails on an object reference, an std::bad_cast exception will be thrown. The last section of this chapter discusses the different options for casting in more detail.

The previous example could have been written as follows:

void lessPresumptuous(Base* base){ Derived* myDerived { dynamic_cast<Derived*>(base) }; if (myDerived != nullptr) { // Proceed to access Derived member functions on myDerived. }}However, keep in mind that the use of downcasting is often a sign of a bad design. You should rethink and modify your design so that downcasting can be avoided. For example, the lessPresumptuous() function only really works with Derived objects, so instead of accepting a Base pointer, it should simply accept a Derived pointer. This eliminates the need for any downcasting. If the function should work with different derived classes, all inheriting from Base, then look for a solution that uses polymorphism, which is discussed next.

Use downcasting only when really necessary, and be sure to use dynamic_cast().

INHERITANCE FOR POLYMORPHISM

Section titled “INHERITANCE FOR POLYMORPHISM”Now that you understand the relationship between a derived class and its parent, you can use inheritance in its most powerful scenario—polymorphism. Chapter 5 discusses how polymorphism allows you to use objects with a common parent class interchangeably and to use objects in place of their parents.

Return of the Spreadsheet

Section titled “Return of the Spreadsheet”Chapters 8 and 9 use a spreadsheet program as an example of an application that lends itself to an object-oriented design. A SpreadsheetCell represents a single element of data. Up to now, that element always stored a single double value. A simplified class definition for SpreadsheetCell follows. Note that a cell can be set either as a double or as a string_view, but it is always stored as a double. The current value of the cell, however, is always returned as a string for this example.

class SpreadsheetCell{ public: virtual void set(double value); virtual void set(std::string_view value); virtual std::string getString() const; private: static std::string doubleToString(double value); static double stringToDouble(std::string_view value); double m_value;};In a real spreadsheet application, cells can store different things. A cell could store a double, but it might just as well store a piece of text. There could also be a need for additional types of cells, such as a formula cell or a date cell. How can you support this?

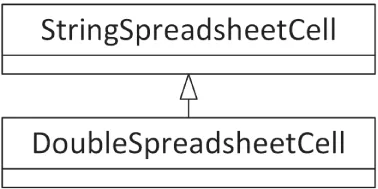

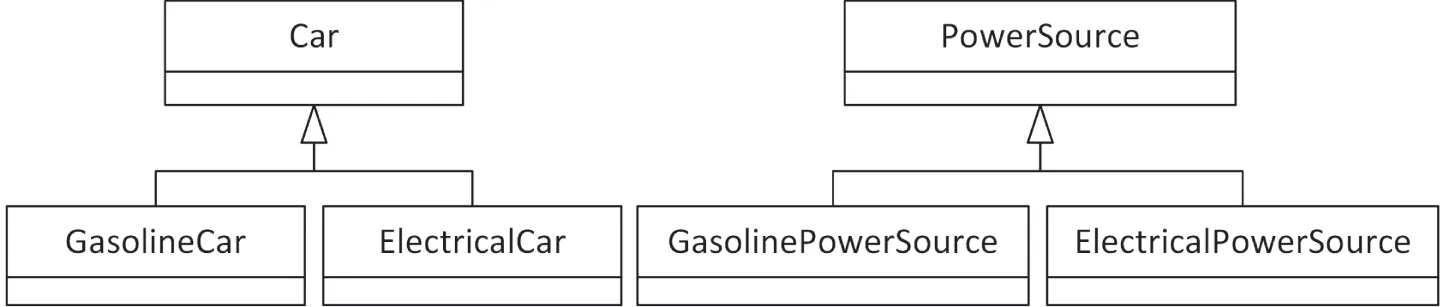

Designing the Polymorphic Spreadsheet Cell

Section titled “Designing the Polymorphic Spreadsheet Cell”The SpreadsheetCell class is screaming out for a hierarchical makeover. A reasonable approach would be to narrow the scope of the SpreadsheetCell to cover only strings, perhaps renaming it to StringSpreadsheetCell in the process. To handle doubles, a second class, DoubleSpreadsheetCell, would inherit from the StringSpreadsheetCell and provide functionality specific to its own format. Figure 10.7 illustrates such a design. This approach models inheritance for reuse because the DoubleSpreadsheetCell would be deriving from StringSpreadsheetCell only to make use of some of its built-in functionality.

[^FIGURE 10.7]

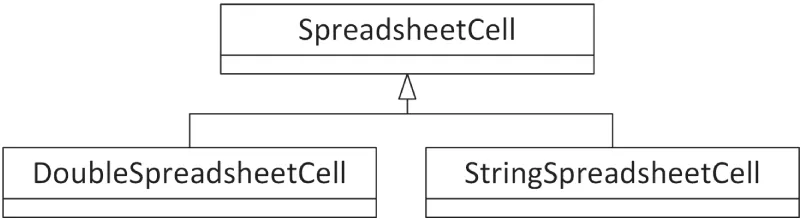

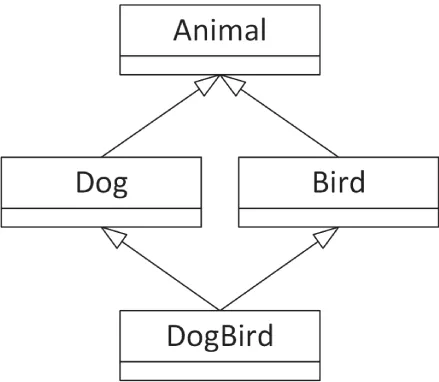

If you were to implement the design shown in Figure 10.7, you might discover that the derived class would override most, if not all, of the functionality of the base class. Because doubles are treated differently from strings in almost all cases, the relationship may not be quite as it was originally understood. Yet, there clearly is a relationship between a cell containing strings and a cell containing doubles. Rather than using the model in Figure 10.7, which implies that somehow a DoubleSpreadsheetCell “is-a” StringSpreadsheetCell, a better design would make these classes peers with a common parent, SpreadsheetCell. Figure 10.8 shows such a design.

[^FIGURE 10.8]

The design in Figure 10.8 shows a polymorphic approach to the SpreadsheetCell hierarchy. Because DoubleSpreadsheetCell and StringSpreadsheetCell both inherit from a common parent, SpreadsheetCell, they are interchangeable in the view of other code. In practical terms, that means the following:

- Both derived classes support the same interface (set of member functions) defined by the base class.

- Code that makes use of

SpreadsheetCellobjects can call any member function in the interface without even knowing whether the cell is aDoubleSpreadsheetCellor aStringSpreadsheetCell. - Through the magic of

virtualmember functions, the appropriate instance of every member function in the interface is called depending on the class of the object. - Other data structures, such as the

Spreadsheetclass described in Chapter 9, can contain a collection of multityped cells by referring to the base type.

The SpreadsheetCell Base Class

Section titled “The SpreadsheetCell Base Class”Because all spreadsheet cells are deriving from the SpreadsheetCell base class, it is probably a good idea to write that class first. When designing a base class, you need to consider how the derived classes relate to each other. From this information, you can derive the commonality that will go inside the parent class. For example, string cells and double cells are similar in that they both contain a single piece of data. Because the data is coming from the user and will be displayed back to the user, the value is set as a string and retrieved as a string. These behaviors are the shared functionality that will make up the base class.

A First Attempt

Section titled “A First Attempt”The SpreadsheetCell base class is responsible for defining the behaviors that all SpreadsheetCell-derived classes will support. In this example, all cells need to be able to set their value as a string. All cells also need to be able to return their current value as a string. The base class definition declares these member functions, as well as an explicitly defaulted virtual destructor, but note that it has no data members. The definition is in a spreadsheet_cell module.

export module spreadsheet_cell;import std;

export class SpreadsheetCell{ public: virtual ˜SpreadsheetCell() = default; virtual void set(std::string_view value); virtual std::string getString() const;};When you start writing the .cpp file for this class, you quickly run into a problem. Considering that the base class of the spreadsheet cell contains neither a double nor a string data member, how can you implement it? More generally, how do you write a base class that declares the behaviors that are supported by derived classes without actually defining the implementation of those behaviors?

One possible approach is to implement “do nothing” functionality for those behaviors. For example, calling the set() member function on the SpreadsheetCell base class will have no effect because the base class has nothing to set. This approach still doesn’t feel right, however. Ideally, there should never be an object that is an instance of the base class. Calling set() should always have an effect because it should always be called on either a DoubleSpreadsheetCell or a StringSpreadsheetCell. A good solution enforces this constraint.

Pure virtual Member Functions and Abstract Base Classes

Section titled “Pure virtual Member Functions and Abstract Base Classes”Pure virtual member functions are member functions that are explicitly undefined in the class definition. By making a member function pure virtual, you are telling the compiler that no definition for the member function exists in the current class. A class with at least one pure virtual member function is said to be an abstract class because no other code will be able to instantiate it. The compiler enforces the fact that if a class contains one or more pure virtual member functions, it can never be used to construct an object of that type.

There is a special syntax for designating a pure virtual member function. The member function declaration is followed by =0. No implementation needs to be written.

export class SpreadsheetCell{ public: virtual ˜SpreadsheetCell() = default; virtual void set(std::string_view value) = 0; virtual std::string getString() const = 0;};Now that the base class is an abstract class, it is impossible to create a SpreadsheetCell object. The following code does not compile and returns an error such as “‘SpreadsheetCell’: cannot instantiate abstract class”:

SpreadsheetCell cell; // Error! Attempts creating abstract class instance.However, once the StringSpreadsheetCell class has been implemented, the following code will compile fine because it instantiates a derived class of the abstract base class:

unique_ptr<SpreadsheetCell> cell { new StringSpreadsheetCell {} };Note that there is nothing to implement for the SpreadsheetCell class. All member functions are pure virtual, and the destructor is explicitly defaulted.

The Individual Derived Classes

Section titled “The Individual Derived Classes”Writing the StringSpreadsheetCell and DoubleSpreadsheetCell classes is just a matter of implementing the functionality that is defined in the parent. Because you want clients to be able to instantiate and work with string cells and double cells, the cells can’t be abstract—they must implement all of the pure virtual member functions inherited from their parent. If a derived class does not implement all pure virtual member functions from the base class, then the derived class is abstract as well, and clients will not be able to instantiate objects of the derived class.

StringSpreadsheetCell Class Definition

Section titled “StringSpreadsheetCell Class Definition”The StringSpreadsheetCell class is defined in its own module called string_spreadsheet_cell. The first step in writing the class definition of StringSpreadsheetCell is to inherit from SpreadsheetCell. For this, the spreadsheet_cell module needs to be imported.

Next, the inherited pure virtual member functions are overridden, this time without being set to zero.

Finally, the string cell adds a private data member, m_value, which stores the actual cell data. This data member is an std::optional, introduced in Chapter 1, “A Crash Course in C++ and the Standard Library.” By using an optional, it is possible to distinguish whether a value for a cell has never been set or whether it was set to the empty string.

export module string_spreadsheet_cell;export import spreadsheet_cell;import std;

export class StringSpreadsheetCell : public SpreadsheetCell{ public: void set(std::string_view value) override; std::string getString() const override; private: std::optional<std::string> m_value;};StringSpreadsheetCell Implementation

Section titled “StringSpreadsheetCell Implementation”The set() member function is straightforward because the internal representation is already a string. The getString() member function has to keep into account that m_value is of type optional and that it might not have a value. When m_value doesn’t have a value, getString() should return a default string, the empty string for this example. This is made easy with the value_or() member function of optional. By using m_value.value_or(""), the real value is returned if m_value contains an actual value; otherwise, the empty string is returned.

void set(std::string_view value) override { m_value = value; }std::string getString() const override { return m_value.value_or(""); }DoubleSpreadsheetCell Class Definition and Implementation

Section titled “DoubleSpreadsheetCell Class Definition and Implementation”The double version follows a similar pattern, but with different logic. In addition to the set() member function from the base class that takes a string_view, it also provides a new set() member function that allows a client to set the value with a double argument. Additionally, it provides a new getValue() member function to retrieve the value as a double. Two new private static member functions are used to convert between a string and a double, and vice versa. As in StringSpreadsheetCell, it has a data member called m_value, this time of type optional<double>.

export module double_spreadsheet_cell;export import spreadsheet_cell;import std;

export class DoubleSpreadsheetCell : public SpreadsheetCell{ public: virtual void set(double value); virtual double getValue() const;

void set(std::string_view value) override; std::string getString() const override; private: static std::string doubleToString(double value); static double stringToDouble(std::string_view value); std::optional<double> m_value;};The set() member function that takes a double is straightforward, as is the implementation of getValue(). The string_view overload uses the private static member function stringToDouble(). The getString() member function returns the stored double value as a string, or returns an empty string if no value has been stored. It uses the has_value() member function of std::optional to query whether the optional has a value. If it has a value, the value() member function is used to retrieve it.

virtual void set(double value) { m_value = value; }virtual double getValue() const { return m_value.value_or(0); }

void set(std::string_view value) override { m_value = stringToDouble(value); }std::string getString() const override{ return (m_value.has_value() ? doubleToString(m_value.value()) : "");}You may already see one major advantage of implementing spreadsheet cells in a hierarchy—the code is much simpler. Each class can be self-centered and deal only with its own functionality.

Note that the implementations of doubleToString() and stringToDouble() are omitted because they are the same as in Chapter 8.

Leveraging Polymorphism

Section titled “Leveraging Polymorphism”Now that the SpreadsheetCell hierarchy is polymorphic, client code can take advantage of the many benefits that polymorphism has to offer. The following test program explores many of these features.

To demonstrate polymorphism, the test program declares a vector of three SpreadsheetCell pointers. Remember that because SpreadsheetCell is an abstract class, you can’t create objects of that type. However, you can still have a pointer or reference to a SpreadsheetCell because it would actually be pointing to one of the derived classes. This vector, because it is a vector of the parent type SpreadsheetCell, allows you to store a heterogeneous mixture of the two derived classes. This means that elements of the vector could be either a StringSpreadsheetCell or a DoubleSpreadsheetCell.

vector<unique_ptr<SpreadsheetCell>> cellArray;The first two elements of the vector are set to point to a new StringSpreadsheetCell, while the third is a new DoubleSpreadsheetCell.

cellArray.push_back(make_unique<StringSpreadsheetCell>());cellArray.push_back(make_unique<StringSpreadsheetCell>());cellArray.push_back(make_unique<DoubleSpreadsheetCell>());Now that the vector contains multityped data, any of the member functions declared by the base class can be applied to the objects in the vector. The code just uses SpreadsheetCell pointers—the compiler has no idea at compile time what types the objects actually are. However, because the objects are inheriting from SpreadsheetCell, they must support the member functions of SpreadsheetCell.

cellArray[0]->set("hello");cellArray[1]->set("10");cellArray[2]->set("18");When the getString() member function is called, each object properly returns a string representation of their value. The important, and somewhat amazing, thing to realize is that the different objects do this in different ways. A StringSpreadsheetCell returns its stored value, or an empty string. A DoubleSpreadsheetCell first performs a conversion if it contains a value; otherwise, it returns an empty string. As the programmer, you don’t need to know how the object does it—you just need to know that because the object is a SpreadsheetCell, it can perform this behavior.

println("Vector: [{},{},{}]", cellArray[0]->getString(), cellArray[1]->getString(), cellArray[2]->getString());Future Considerations

Section titled “Future Considerations”The new implementation of the SpreadsheetCell hierarchy is certainly an improvement from an object-oriented design point of view. Yet, it would probably not suffice as an actual class hierarchy for a real-world spreadsheet program for several reasons.

First, despite the improved design, one feature is still missing: the ability to convert from one cell type to another. By dividing them into two classes, the cell objects become more loosely integrated. To provide the ability to convert from a DoubleSpreadsheetCell to a StringSpreadsheetCell, you could add a converting constructor, also known as a typed constructor. It has a similar appearance as a copy constructor, but instead of a reference to an object of the same class, it takes a reference to an object of a sibling class. Note also that you now have to declare a default constructor, which can be explicitly defaulted, because the compiler stops generating one as soon as you declare any constructor yourself.

export class StringSpreadsheetCell : public SpreadsheetCell{ public: StringSpreadsheetCell() = default; StringSpreadsheetCell(const DoubleSpreadsheetCell& cell) : m_value { cell.getString() } { } // Remainder omitted for brevity.};With a converting constructor, you can easily create a StringSpreadsheetCell given a DoubleSpreadsheetCell. Don’t confuse this with casting pointers or references, however. Casting from one sibling pointer or reference to another does not work, unless you overload the cast operator as described in Chapter 15, “Overloading C++ Operators.”

You can always cast up the hierarchy, and you can sometimes cast down the hierarchy. Casting across the hierarchy is possible by changing the behavior of the cast operator or by using reinterpret_cast(), neither of which is recommended.

Second, the question of how to implement overloaded operators for cells is an interesting one, and there are several possible approaches.

One approach is to implement a version of each operator for every combination of cells. With only two derived classes, this is manageable. There would be an operator+ function to add two double cells, to add two string cells, and to add a double cell to a string cell. For each combination, you decide what the result is. For example, the result of adding two double cells could be the result of mathematically adding both values together. The result of adding two string cells could be a string representing the concatenation of both strings, and so on.

Another approach is to decide on a common representation. The earlier implementation already standardizes on a string as a common representation of sorts. A single operator+ could cover all the cases by taking advantage of this common representation.

Yet another approach is a hybrid one. One operator+ can be provided that adds two DoubleSpreadsheetCells resulting in a DoubleSpreadsheetCell. This operator can be implemented in the double_spreadsheet_cell module as follows:

export DoubleSpreadsheetCell operator+(const DoubleSpreadsheetCell& lhs, const DoubleSpreadsheetCell& rhs){ DoubleSpreadsheetCell newCell; newCell.set(lhs.getValue() + rhs.getValue()); return newCell;}This operator can be tested as follows:

DoubleSpreadsheetCell doubleCell; doubleCell.set(8.4);DoubleSpreadsheetCell result { doubleCell + doubleCell };println("{}", result.getString()); // Prints 16.800000A second operator+ can be provided for use when at least one of the two operands is a StringSpreadsheetCell. You could decide that the result of this operator should always be a string cell. Such an operator can be added to the string_spreadsheet_cell module and can be implemented as follows:

export StringSpreadsheetCell operator+(const StringSpreadsheetCell& lhs, const StringSpreadsheetCell& rhs){ StringSpreadsheetCell newCell; newCell.set(lhs.getString() + rhs.getString()); return newCell;}As long as the compiler has a way to turn a particular cell into a StringSpreadsheetCell, the operator will work. Given the previous example of having a StringSpreadsheetCell constructor that takes a DoubleSpreadsheetCell as an argument, the compiler will automatically perform the conversion if it is the only way to get the operator+ to work. That means the following code adding a double cell to a string cell works, even though there are only two operator+ implementations provided: one adding two double cells and one adding two string cells.

DoubleSpreadsheetCell doubleCell; doubleCell.set(8.4);StringSpreadsheetCell stringCell; stringCell.set("Hello ");StringSpreadsheetCell result { stringCell + doubleCell };println("{}", result.getString()); // Prints Hello 8.400000If you are feeling a little unsure about polymorphism, start with the code for this example and try things out. It is a great starting point for experimental code that simply exercises various aspects of polymorphism.

Providing Implementations for Pure virtual Member Functions

Section titled “Providing Implementations for Pure virtual Member Functions”Technically, it is possible to provide an implementation for a pure virtual member function. This implementation cannot be in the class definition itself but must be provided outside. The class remains abstract though, and any derived classes are still required to provide an implementation of the pure virtual member function. Since the class remains abstract, no instances of it can be created. Still, its implementation of the pure virtual member function can be called, for example, from a derived class. The following code snippet demonstrates this:

class Base{public: virtual void doSomething() = 0; // Pure virtual member function.};

// An out-of-class implementation of a pure virtual member function.void Base::doSomething() { println("Base::doSomething()"); }

class Derived : public Base{public: void doSomething() override { // Call pure virtual member function implementation from base class. Base::doSomething(); println("Derived::doSomething()"); }};

int main(){ Derived derived; Base& base { derived }; base.doSomething();}The output is as expected:

Base::doSomething()Derived::doSomething()MULTIPLE INHERITANCE

Section titled “MULTIPLE INHERITANCE”As you read in Chapter 5, multiple inheritance is often perceived as a complicated and unnecessary part of object-oriented programming. I’ll leave the decision of whether it is useful up to you and your co-workers. This section explains the mechanics of multiple inheritance in C++.

Inheriting from Multiple Classes

Section titled “Inheriting from Multiple Classes”Defining a class to have multiple parent classes is simple from a syntactic point of view. All you need to do is list the base classes individually when declaring the class name.

class Baz : public Foo, public Bar { /* Etc. */ };By listing multiple parents, a Baz object has the following characteristics:

- A

Bazobject supports thepublicmember functions and contains the data members of bothFooandBar. - The member functions of the

Bazclass have access toprotecteddata and member functions in bothFooandBar. - A

Bazobject can be upcast to either aFooor aBar. - Creating a new

Bazobject automatically calls theFooandBardefault constructors, in the order in which the classes are listed in the class definition. - Deleting a

Bazobject automatically calls the destructors for theFooandBarclasses, in the reverse order that the classes are listed in the class definition.

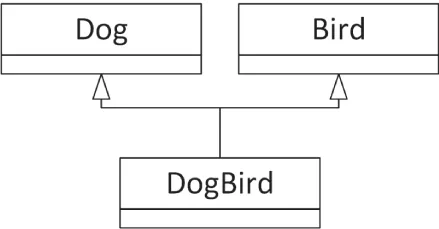

The following example shows a class, DogBird, that has two parent classes—a Dog class and a Bird class, as shown in Figure 10.9. The fact that a dog-bird is a ridiculous example should not be viewed as a statement that multiple inheritance itself is ridiculous. Honestly, I leave that judgment up to you.

[^FIGURE 10.9]

class Dog{ public: virtual void bark() { println("Woof!"); }};

class Bird{ public: virtual void chirp() { println("Chirp!"); }};

class DogBird : public Dog, public Bird{};Using objects of classes with multiple parents is no different from using objects without multiple parents. In fact, the client code doesn’t even have to know that the class has two parents. All that really matters are the properties and behaviors supported by the class. In this case, a DogBird object supports all of the public member functions of Dog and Bird.

DogBird myConfusedAnimal;myConfusedAnimal.bark();myConfusedAnimal.chirp();The output of this program is as follows:

Woof!Chirp!Naming Collisions and Ambiguous Base Classes

Section titled “Naming Collisions and Ambiguous Base Classes”It’s not difficult to construct a scenario where multiple inheritance would seem to break down. The following examples show some of the edge cases that must be considered.

Name Ambiguity

Section titled “Name Ambiguity”What if the Dog class and the Bird class both had a member function called eat()? Because Dog and Bird are not related in any way, one version of the member function does not override the other—they both continue to exist in the DogBird-derived class.

As long as client code never attempts to call the eat() member function, that is not a problem. The DogBird class compiles correctly despite having two versions of eat(). However, if client code attempts to call the eat() member function on a DogBird, the compiler gives an error indicating that the call to eat() is ambiguous. The compiler does not know which version to call. The following code provokes this ambiguity error:

class Dog{ public: virtual void bark() { println("Woof!"); } virtual void eat() { println("The dog ate."); }};

class Bird{ public: virtual void chirp() { println("Chirp!"); } virtual void eat() { println("The bird ate."); }};

class DogBird : public Dog, public Bird{};

int main(){ DogBird myConfusedAnimal; myConfusedAnimal.eat(); // Error! Ambiguous call to member function eat()}If you comment out the last line from main() calling eat(), the code compiles fine.

The solution to the ambiguity is either to explicitly upcast the object using a dynamic_cast(), essentially hiding the undesired version of the member function from the compiler, or to use a disambiguation syntax. For example, the following code shows two ways to invoke the Dog version of eat():

dynamic_cast<Dog&>(myConfusedAnimal).eat(); // Calls Dog::eat()myConfusedAnimal.Dog::eat(); // Calls Dog::eat()Member functions of the derived class itself can also explicitly disambiguate between different member functions of the same name by using the same syntax used to access parent member functions, that is, the :: scope resolution operator. For example, the DogBird class could prevent ambiguity errors in other code by defining its own eat() member function. Inside this member function, it would determine which parent version to call.

class DogBird : public Dog, public Bird{ public: void eat() override { Dog::eat(); // Explicitly call Dog's version of eat() }};Yet another way to prevent the ambiguity error is to use a using declaration to explicitly state which version of eat() should be inherited in DogBird. Here’s an example:

class DogBird : public Dog, public Bird{ public: using Dog::eat; // Explicitly inherit Dog's version of eat()};Ambiguous Base Classes

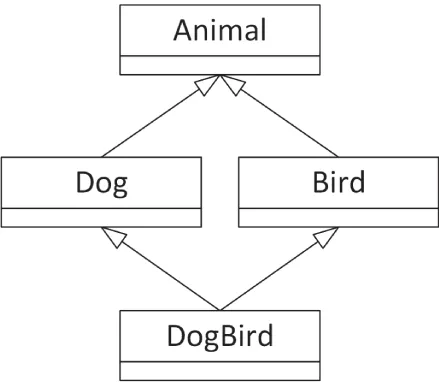

Section titled “Ambiguous Base Classes”Another way to provoke ambiguity is to inherit from the same class twice. This can happen if multiple parents themselves have a common parent. For example, perhaps both Bird and Dog are inheriting from an Animal class, as shown in Figure 10.10.

[^FIGURE 10.10]

This type of class hierarchy is permitted in C++, though name ambiguity can still occur. For example, if the Animal class has a public member function called sleep(), that member function cannot be called on a DogBird object because the compiler does not know whether to call the version inherited by Dog or by Bird.

The best way to use these “diamond-shaped” class hierarchies is to make the topmost class an abstract base class with all member functions declared as pure virtual. Because the class only declares member functions without providing definitions, there are no member functions in the base class to call, and thus there are no ambiguities at that level.