Handling Errors

Inevitably, your C++ programs will encounter errors during execution. The program might be unable to open a file, the network connection might go down, or the user might enter an incorrect value, to name a few possibilities. The C++ language provides a feature called exceptions to handle these exceptional but not unexpected situations.

Most code examples in this book so far have generally ignored error conditions for brevity. This chapter rectifies that simplification by teaching you how to incorporate error handling into your programs from their beginnings. It focuses on C++ exceptions, including the details of their syntax, and describes how to employ them effectively to create well-designed error-handling programs.

The chapter also discusses how you can write your own exception classes. This includes discussing how to automatically embed both, the exact location in your source code where an exception occurred, as well as the full stack trace at the moment the exception was raised. Both of these help tremendously in diagnosing any errors.

ERRORS AND EXCEPTIONS

Section titled “ERRORS AND EXCEPTIONS”No program exists in isolation; they all depend on external facilities such as interfaces with the operating system, networks and file systems, external code such as third-party libraries, and user input. Each of these areas can introduce situations that require you to respond to problems your program may encounter. These potential problems can be referred to with the general term exceptional situations. Even perfectly written programs encounter errors and exceptional situations. Thus, anyone who writes professional computer programs must include error-handling capabilities. Some languages, such as C, do not include many specific language facilities for error handling. Programmers using these languages generally rely on return values from functions and other ad hoc approaches. Other languages, such as Java, enforce the use of a language feature called exceptions as an error-handling mechanism. C++ lies between these extremes. It provides language support for exceptions but does not require their use. However, you can’t ignore exceptions entirely in C++ because a few basic facilities, such as memory allocation routines, use them by default, and several classes from the Standard Library use exceptions as well.

What Are Exceptions, Anyway?

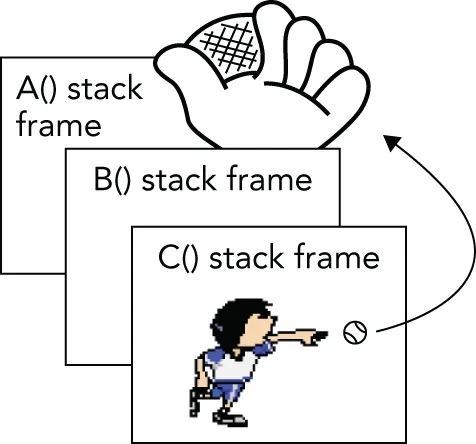

Section titled “What Are Exceptions, Anyway?”Exceptions are a mechanism for a piece of code to notify another piece of code of an “exceptional” situation or error condition without progressing through the normal code paths. The code that encounters the error throws the exception, and the code that handles the exception catches it. Exceptions do not follow the fundamental rule of step-by-step execution to which you are accustomed. When a piece of code throws an exception, the program control immediately stops executing code step-by-step and transitions to the exception handler, which could be anywhere from the next line in the same function to several function calls up the stack. If you like sports analogies, you can think of the code that throws an exception as an outfielder throwing a baseball back to the infield, where the nearest infielder (closest exception handler) catches it. Figure 14.1 shows a hypothetical stack of three function calls. Function A() has the exception handler. It calls function B(), which calls function C(), which throws the exception.

[^FIGURE 14.1]

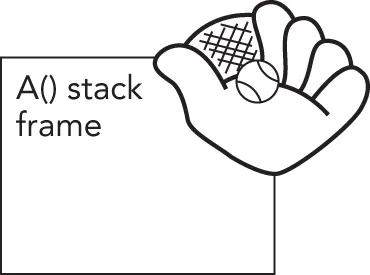

Figure 14.2 shows the handler catching the exception. The stack frames for C() and B() have been removed, leaving only A().

[^FIGURE 14.2]

Most modern programming languages, such as C# and Java, have support for exceptions, so it’s no surprise that C++ has full-fledged support for them as well. However, if you are coming from C, then exceptions are something new; but once you get used to them, you probably don’t want to go back.

Why Exceptions in C++ Are a Good Thing

Section titled “Why Exceptions in C++ Are a Good Thing”As mentioned earlier, run-time errors in programs are inevitable. Despite that fact, error handling in most C and C++ programs is messy and ad hoc. The de facto C error-handling standard, which was carried over into many C++ programs, uses integer function return codes, and the errno macro to signify errors. Each thread has its own errno value. errno acts as a thread-local integer variable that functions can use to communicate errors back to calling functions.

Unfortunately, the integer return codes and errno are used inconsistently. Some functions might choose to return 0 for success and -1 for an error. If they return -1, they also set errno to an error code. Other functions return 0 for success and nonzero for an error, with the actual return value specifying the error code. These functions do not use errno. Still others return 0 for failure instead of for success, presumably because 0 always evaluates to false in C and C++.

These inconsistencies can cause problems because programmers encountering a new function often assume that its return codes are the same as other similar functions. That is not always true. For example, on the Solaris 11 operating system, there are two different libraries of synchronization objects: the Portable Operating System Interface (POSIX) version and the Solaris version. The function to initialize a semaphore in the POSIX version is called sem_init(), and the function to initialize a semaphore in the Solaris version is called sema_init(). As if that weren’t confusing enough, the two functions handle error codes differently! sem_init() returns -1 and sets errno on error, while sema_init() returns the error code directly as a positive integer and does not set errno.

Another problem is that the return type of functions in C++ can be of only one type, so if you need to return both an error and a value, you must find an alternative mechanism. One solution is to return an std::pair or tuple, an object that you can use to store two or more types. The pair class is introduced in Chapter 1, “A Crash Course in C++ and the Standard Library,” while tuple is discussed in the upcoming chapters that cover the Standard Library. Starting with C++23, you can return an std::expected from a function, which can contain either the result of the function or an error if something went wrong. Chapter 24, “Additional Vocabulary Types,” discusses expected in detail. Another choice is to define your own struct or class that contains several values and return an instance of that struct or class from your function. Yet another option is to return the value or error through a reference parameter or to make the error code one possible value of the return type, such as a nullptr pointer. In all these solutions, the caller is responsible for explicitly checking for any errors returned from the function, and if it doesn’t handle the error itself, it should propagate the error to its caller. Unfortunately, this often results in the loss of critical details about the error.

C programmers may be familiar with a mechanism known as setjmp()/longjmp(). This mechanism cannot be used correctly in C++, because it bypasses scoped destructors on the stack. You should avoid it at all costs, even in C programs; therefore, this book does not explain the details of how to use it.

Exceptions provide an easier, more consistent, and safer mechanism for error handling. There are several specific advantages of exceptions over the ad hoc approaches in C and C++:

- When return codes are used as an error reporting mechanism, you might forget to check the return code and properly handle it either locally or by propagating it upward. The

[[nodiscard]]attribute, introduced in Chapter 1, offers a possible solution to prevent return codes from being ignored, but it’s not foolproof either. Exceptions cannot be forgotten or ignored: if your program fails to catch an exception, it terminates. - When integer return codes are used, they generally do not contain sufficient information. You can use exceptions to pass as much information as you want from the code that finds the error to the code that handles it. Exceptions can also be used to communicate information other than errors, though many developers, including myself, consider that an abuse of the exception mechanism.

- Exception handling can skip levels of the call stack. That is, a function can handle an error that occurred several function calls down the stack, without error-handling code in the intermediate functions. Return codes require each level of the call stack to clean up explicitly after the previous level and to explicitly propagate the error code.

In some compilers in the past, exception handling added a tiny amount of overhead to any function that had an exception handler. For most modern compilers there is a trade-off in that there is almost no, or even zero, overhead in the non-throwing case, and only some slight overhead when you actually throw something. This trade-off is not a bad thing. Exceptions should not be used for controlling the standard execution flow of a program, such as returning a value from a function. Exceptions should be used only to handle exceptional events that are generally not encountered in normal program use, for example, a failure while reading from a file on disk. All this means that using exceptions actually results in faster code for the non-error case compared to an implementation using error return codes.

Exception handling is not enforced in C++. In Java, for example, it is enforced. A Java function that does not specify a list of exceptions that it can possibly throw is not allowed to throw any exceptions. In C++, it is just the opposite: a function can throw any exception it wants, unless it specifies that it will not throw any exceptions using the noexcept keyword, which is discussed later in this chapter!

Recommendation

Section titled “Recommendation”I recommend exceptions as a useful mechanism for error handling. I feel that the structure and error-handling formalization that exceptions provide outweigh the less desirable aspects. Thus, the remainder of this chapter focuses on exceptions. Also, many popular libraries, such as the Standard Library and Boost, use exceptions, so you need to be prepared to handle them.

EXCEPTION MECHANICS

Section titled “EXCEPTION MECHANICS”Exceptional situations arise frequently in file input and output. The following is a function to open a file, read a list of integers from the file, and return the integers in an std::vector data structure. The lack of error handling should jump out at you:

vector<int> readIntegerFile(const string& filename){ ifstream inputStream { filename }; // Read the integers one-by-one and add them to a vector. vector<int> integers; int temp; while (inputStream >> temp) { integers.push_back(temp); } return integers;}The following line keeps reading values from the ifstream until the end of the file is reached or until an error occurs:

while (inputStream>> temp) {If the >> operator encounters an error, it sets the fail bit of the ifstream object. In that case, the bool() conversion operator returns false, and the while loop terminates. Streams are discussed in more detail in Chapter 13, “Demystifying C++ I/O.”

You might use readIntegerFile() like this:

const string filename { "IntegerFile.txt" };vector<int> myInts { readIntegerFile(filename) };println("{} ", myInts);The rest of this section shows how to add error handling with exceptions, but first, we need to delve a bit deeper into how you throw and catch exceptions.

Throwing and Catching Exceptions

Section titled “Throwing and Catching Exceptions”Using exceptions consists of providing two parts in your program: a try/catch construct to handle an exception, and a throw statement that throws an exception. Both must be present in some form to make exceptions work. However, in many cases, the throw happens deep inside some library (including the C++ runtime), and the programmer never sees it, but still has to react to it using a try/catch construct.

The try/catch construct looks like this:

try { // … code which may result in an exception being thrown} catch (exception-type1 exception-name) { // … code which responds to the exception of type 1} catch (exception-type2 exception-name) { // … code which responds to the exception of type 2}// … remaining codeThe code that may result in an exception being thrown might contain a throw directly. It might also be calling a function that either directly throws an exception or calls—by some unknown number of layers of calls—a function that throws an exception.

If no exception is thrown, no code from any catch block is executed, and the “remaining code” that follows will follow the last statement executed in the try block.

If an exception is thrown, any code following the throw or following the call that resulted in the throw is not executed; instead, control immediately goes to the right catch block, depending on the type of the exception that is thrown.

If the catch block does not do a control transfer—for example, by returning from the function, throwing a new exception, or rethrowing the caught exception—then the “remaining code” is executed after the last statement of that catch block.

The simplest example to demonstrate exception handling is avoiding division-by-zero. The following example throws an exception of type std::invalid_argument, defined in <stdexcept>:

double safeDivide(double num, double den){ if (den == 0) { throw invalid_argument { "Divide by zero" }; } return num / den;}

int main(){ try { println("{}", safeDivide(5, 2)); println("{}", safeDivide(10, 0)); println("{}", safeDivide(3, 3)); } catch (const invalid_argument& e) { println("Caught exception: {}", e.what()); }}The output is as follows:

2.5Caught exception: Divide by zerothrow is a keyword in C++ and is the only way to throw an exception. In the code snippet we throw a new instance of invalid_argument. It is one of the standard exceptions provided by the C++ Standard Library. All Standard Library exceptions form a hierarchy, which is discussed later in this chapter. Each class in the hierarchy supports a what() member function that returns a const char* string describing the exception. This is the string you provide in the constructor of the exception.

Let’s go back to the readIntegerFile() function. The most likely problem to occur is for the file open to fail. That’s a perfect situation for throwing an exception. The following code throws an exception of type std::exception, defined in <exception>, if the file fails to open:

vector<int> readIntegerFile(const string& filename){ ifstream inputStream { filename }; if (inputStream.fail()) { // We failed to open the file: throw an exception. throw exception {}; }

// Read the integers one-by-one and add them to a vector. vector<int> integers; int temp; while (inputStream >> temp) { integers.push_back(temp); } return integers;}If the function fails to open the file and executes the throw exception{}; statement, the rest of the function is skipped, and control transitions to the nearest exception handler.

Throwing exceptions in your code is most useful when you also write code that handles them. Exception handling is a way to “try” a block of code, with another block of code designated to react to any problems that might occur. In the following main() function, the catch statement reacts to any exception of type exception that was thrown within the try block by printing an error message. If a try block finishes without throwing an exception, the catch blocks are skipped. You can think of try/catch blocks as glorified if statements: if an exception is thrown in the try block, then execute a catch block, else skip all catch blocks.

int main(){ const string filename { "IntegerFile.txt" }; vector<int> myInts; try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename); } catch (const exception& e) { println(cerr, "Unable to open file {}", filename); return 1; } println("{} ", myInts);}Exception Types

Section titled “Exception Types”You can throw an exception of any type. The earlier example throws an object of type std::exception, but exceptions do not need to be objects. You could throw a simple int like this:

vector<int> readIntegerFile(const string& filename){ ifstream inputStream { filename }; if (inputStream.fail()) { // We failed to open the file: throw an exception. throw 5; } // Omitted for brevity}You would then need to change the catch statement as follows:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (int e) { println(cerr, "Unable to open file {} (Error Code {})", filename, e); return 1;}Alternatively, you could throw a const char* C-style string. This technique is sometimes useful because the string can contain information about the exception:

vector<int> readIntegerFile(const string& filename){ ifstream inputStream { filename }; if (inputStream.fail()) { // We failed to open the file: throw an exception. throw "Unable to open file"; } // Omitted for brevity}When you catch the const char* exception, you can print the result as follows:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (const char* e) { println(cerr, "{}", e); return 1;}Despite the previous examples, keep the following in mind:

You should generally throw objects rather than other data types as exceptions for two reasons:

- Objects convey information by their class name.

- Objects can store all kinds of information, including strings that describe the exception.

The C++ Standard Library defines a number of predefined exception classes structured in a class hierarchy, discussed later in this chapter. Additionally, you can write your own exception classes and fit them in the standard hierarchy, as you’ll also learn later in this chapter.

Catching Exception Objects as Reference-to-const

Section titled “Catching Exception Objects as Reference-to-const”In the earlier example in which readIntegerFile() throws an object of type exception, the catch handler looks like this:

} catch (const exception& e) {However, there is no requirement to catch objects as reference-to-const. You could catch the object by value like this:

} catch (exception e) {Alternatively, you could catch the object as reference-to-non-const:

} catch (exception& e) {Also, as you saw in the const char* example earlier, you can catch pointers to exceptions, as long as pointers to exceptions are thrown.

Still, I recommend sticking with the following advice:

Throwing and Catching Multiple Exceptions

Section titled “Throwing and Catching Multiple Exceptions”Failure to open the file is not the only problem readIntegerFile() could encounter. Reading the data from the file can cause an error if it is formatted incorrectly. Here is an implementation of readIntegerFile() that throws an exception if it cannot either open the file or read the data correctly. This time, it uses a runtime_error, derived from exception and which allows you to specify a descriptive string in its constructor. The runtime_error exception class is defined in <stdexcept>.

vector<int> readIntegerFile(const string& filename){ ifstream inputStream { filename }; if (inputStream.fail()) { // We failed to open the file: throw an exception. throw runtime_error { "Unable to open the file." }; }

// Read the integers one-by-one and add them to a vector. vector<int> integers; int temp; while (inputStream >> temp) { integers.push_back(temp); }

if (!inputStream.eof()) { // We did not reach the end-of-file. // This means that some error occurred while reading the file. // Throw an exception. throw runtime_error { "Error reading the file." }; }

return integers;}Your code in main() does not need to change much because it already catches an exception of type exception, from which runtime_error derives. However, that exception could now be thrown in two different situations, so we use the what() member function to get a proper description of the caught exception:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (const exception& e) { println(cerr, "{}", e.what()); return 1;}Alternatively, you could throw two different types of exceptions from readIntegerFile(). Here is an implementation of readIntegerFile() that throws an exception object of class invalid_argument if the file cannot be opened, and an object of class runtime_error if the integers cannot be read. Both invalid_argument and runtime_error are classes defined in <stdexcept> as part of the C++ Standard Library.

vector<int> readIntegerFile(const string& filename){ ifstream inputStream { filename }; if (inputStream.fail()) { // We failed to open the file: throw an exception. throw invalid_argument { "Unable to open the file." }; }

// Read the integers one-by-one and add them to a vector. vector<int> integers; int temp; while (inputStream >> temp) { integers.push_back(temp); }

if (!inputStream.eof()) { // We did not reach the end-of-file. // This means that some error occurred while reading the file. // Throw an exception. throw runtime_error { "Error reading the file." }; }

return integers;}There are no public default constructors for invalid_argument and runtime_error, only string constructors, so you always must pass a string as argument.

Now, main() can catch both invalid_argument and runtime_error exceptions with two catch statements:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (const invalid_argument& e) { println(cerr, "{}", e.what()); return 1;} catch (const runtime_error& e) { println(cerr, "{}", e.what()); return 2;}If an exception is thrown inside the try block, the compiler matches the type of the exception to the proper catch handler. So, if readIntegerFile() is unable to open the file and throws an invalid_argument object, it is caught by the first catch statement. If readIntegerFile() is unable to read the file properly and throws a runtime_error, then the second catch statement catches the exception.

Matching and const

Section titled “Matching and const”The const-ness specified in the type of the exception you want to catch makes no difference for matching purposes. That is, this line matches any exception of type runtime_error:

} catch (const runtime_error& e) {The following line also matches any exception of type runtime_error:

} catch (runtime_error& e) {Still, it’s advised to always catch exception objects as reference-to-const.

Matching Any Exception

Section titled “Matching Any Exception”You can write a catch-all block that matches any possible exception with the special syntax shown in the following example:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (…) { println(cerr, "Error reading or opening file {}", filename); return 1;}The three dots are not a typo. They are a wildcard that matches any exception type. The downside of using a catch-all block is that you don’t get any details of the caught exception. When you are calling poorly documented code, this technique could be useful to ensure that you catch all possible exceptions. But even then, what would you possibly be able to do to recover from an unknown exception?

One useful use case of a catch-all block is to log that an exception was thrown and then rethrow the exception. The following example shows how you can write catch handlers that explicitly handle invalid_argument and runtime_error exceptions, as well as how to include a catch-all handler for all other exceptions. In any catch block, you can rethrow the currently caught exception using just the throw keyword without any arguments. There is more to say about rethrowing exceptions, but that has to wait until later in this chapter.

try { // Code that can throw exceptions.} catch (const invalid_argument& e) { // Handle invalid_argument exception.} catch (const runtime_error& e) { // Handle runtime_error exception.} catch (…) { // Handle all other exceptions. // Log that an exception occurred… throw; // Rethrow the caught exception.}In situations where you have complete information about the set of thrown exceptions, a catch-all block is not recommended because it handles every exception type identically. It’s better to match exception types explicitly and take appropriate, targeted actions.

Uncaught Exceptions

Section titled “Uncaught Exceptions”If your program throws an exception that is not caught anywhere, the program terminates. Basically, there is a try/catch construct around the call to your main() function, which catches all unhandled exceptions and behaves like the following pseudocode:

try { main(argc, argv);} catch (…) { // Issue error message and terminate program.}// Normal termination code.However, this behavior is usually not what you want. The point of exceptions is to give your program a chance to handle and correct undesirable or unexpected situations.

You should catch and handle all exceptions thrown in your programs, as far as possible.

It is also possible to change the behavior of your program if there is an uncaught exception. When the program encounters an uncaught exception, it calls the built-in terminate() function, which calls abort() from <cstdlib> to kill the program. You can set your own terminate_handler by calling set_terminate() with a pointer to a function that takes no arguments and returns no value. terminate(), set_terminate(), and terminate_handler are all declared in <exception>. The following pseudocode shows a high-level overview of how it works:

try { main(argc, argv);} catch (…) { if (terminate_handler != nullptr) { terminate_handler(); } else { terminate(); }}// Normal termination code.Before you get too excited about this feature, you should know that your callback function must still terminate the program using either abort() or _Exit(). It can’t just ignore the error. Both abort() and _Exit() are defined in <cstdlib> and terminate the application without cleaning up resources. For example, destructors of objects won’t get called. The _Exit() function accepts an integer argument that is returned to the operating system and can be used to determine how a process exited. A value of 0 or EXIT_SUCCESS means the program exited without any error; otherwise, the program terminated abnormally. The abort() function does not accept any arguments. Additionally, there is an exit() function that also accepts an integer that is returned to the operating system and that does clean up resources by calling destructors, but it’s not recommended to call exit() from a terminate_handler.

A terminate_handler can be used to print a helpful error message before exiting. Here is an example of a main() function that doesn’t catch the exceptions thrown by readIntegerFile(). Instead, it sets the terminate_handler to a custom callback. This callback prints an error message and terminates the process by calling _Exit(). Note the use of the [[noreturn]] attribute, introduced in Chapter 1.

[[noreturn]] void myTerminate(){ println(cerr, "Uncaught exception!"); _Exit(1);}

int main(){ set_terminate(myTerminate);

const string filename { "IntegerFile.txt" }; vector<int> myInts { readIntegerFile(filename) }; println("{} ", myInts);}Although not shown in this example, set_terminate() returns the old terminate_handler when it sets the new one. The terminate_handler applies program-wide, so it’s considered good style to restore the old terminate_handler when you have completed the code that needed the new terminate_handler. In this case, the entire program needs the new terminate_handler, so there’s no point in restoring it.

While it’s important to know about set_terminate(), it’s not an effective exception-handling approach. It’s recommended to catch and handle each exception individually to provide more precise error handling.

noexcept Specifier

Section titled “noexcept Specifier”By default, a function is allowed to throw any exception it likes. However, it is possible to mark a function with the noexcept specifier, a C++ keyword, to state that it will not throw any exceptions. For example, the following function is marked as noexcept, so it is not allowed to throw any exceptions:

void printValues(const vector<int>& values) noexcept;When a function marked as noexcept throws an exception anyway, C++ calls terminate() to terminate the application.

When you override a virtual member function in a derived class, you are allowed to mark the overridden member function as noexcept, even if the version in the base class is not noexcept. The opposite is not allowed.

noexcept(expression) Specifier

Section titled “noexcept(expression) Specifier”The noexcept(expression) specifier marks a function as noexcept if and only if the given expression returns true. In other words, noexcept equals noexcept(true), and noexcept(false) is the opposite of noexcept(true); that is, a member function marked with noexcept(false) can throw any exception it wants, which is the default.

noexcept(expression) Operator

Section titled “noexcept(expression) Operator”The noexcept(expression) operator returns true if the given expression is noexcept. This evaluation happens at compile time.

Here’s an example:

void f1() noexcept {}void f2() noexcept(false) {}void f3() noexcept(noexcept(f1())) {}void f4() noexcept(noexcept(f2())) {}

int main(){ println("{} {} {} {}", noexcept(f1()), noexcept(f2()), noexcept(f3()), noexcept(f4()));}The output of this code snippet is true false true false:

noexcept(f1())istruebecausef1()is explicitly marked with anoexceptspecifier.noexcept(f2())isfalsebecausef2()is explicitly marked as such using anoexcept(expression)specifier.noexcept(f3())istruebecausef3()is marked asnoexceptbut only iff1()isnoexceptwhich it is.noexcept(f4())isfalsebecausef4()is marked asnoexceptbut only iff2()isnoexceptwhich it isn’t.

Throw Lists

Section titled “Throw Lists”Older versions of C++ allowed you to specify the exceptions a function intended to throw. This specification was called the throw list or the exception specification.

C++11 has deprecated, and C++17 has removed support for exception specifications, apart from noexcept and throw(). The latter was equivalent to noexcept. Since C++20, support for throw() has been removed as well.

Because C++17 has officially removed support for exception specifications, this book does not further discuss them.

EXCEPTIONS AND POLYMORPHISM

Section titled “EXCEPTIONS AND POLYMORPHISM”As described earlier, you can actually throw any type of exception. However, classes are the most useful types of exceptions. In fact, exception classes are usually written in a hierarchy so that you can employ polymorphism when you catch the exceptions.

The Standard Exception Hierarchy

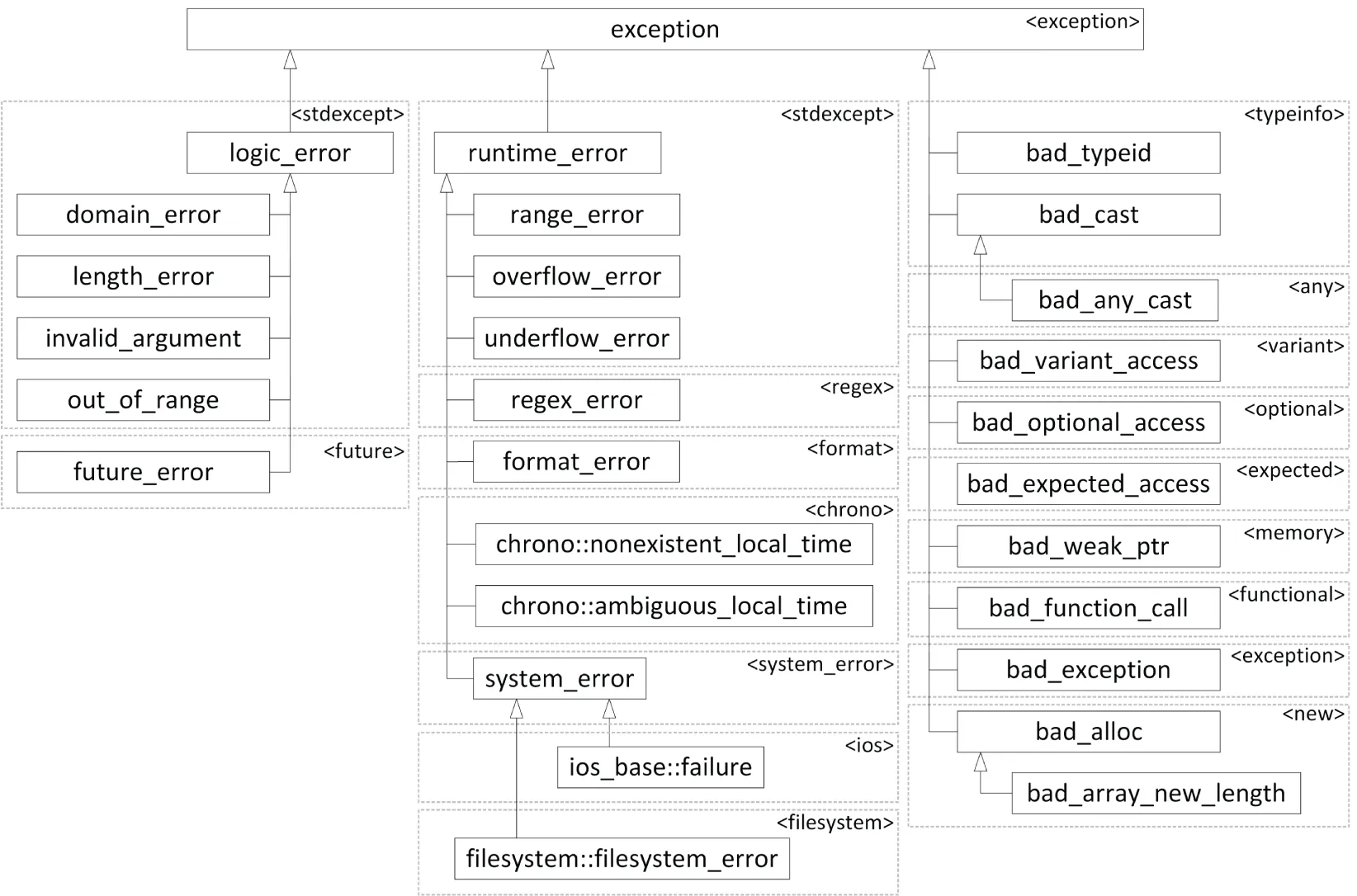

Section titled “The Standard Exception Hierarchy”You’ve already seen several exceptions from the C++ standard exception hierarchy: exception, runtime_error, and invalid_argument. Figure 14.3 shows the full hierarchy. For completeness, all standard exceptions are shown, including those thrown by parts of the Standard Library that are discussed in later chapters.

[^FIGURE 14.3]

All of the exceptions thrown by the C++ Standard Library are objects of classes in this hierarchy. Each class in the hierarchy supports a what() member function that returns a const char* string describing the exception. You can use this string in an error message.

Some of the exception classes require you to set in the constructor the string that is returned by what(). That’s why you have to specify a string in the constructors for runtime_error and invalid_argument. This has already been done in examples throughout this chapter. Here is another version of readIntegerFile() that includes the filename in the error message:

vector<int> readIntegerFile(const string& filename){ ifstream inputStream { filename }; if (inputStream.fail()) { // We failed to open the file: throw an exception. const string error { format("Unable to open file {}.", filename) }; throw invalid_argument { error }; }

// Read the integers one-by-one and add them to a vector. vector<int> integers; int temp; while (inputStream >> temp) { integers.push_back(temp); }

if (!inputStream.eof()) { // We did not reach the end-of-file. // This means that some error occurred while reading the file. // Throw an exception. const string error { format("Unable to read file {}.", filename) }; throw runtime_error { error }; }

return integers;}Catching Exceptions in a Class Hierarchy

Section titled “Catching Exceptions in a Class Hierarchy”A feature of exception hierarchies is that you can catch exceptions polymorphically. For example, if you look at the following two catch statements, you can see that they are identical except for the exception class that they handle:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (const invalid_argument& e) { println(cerr, "{}", e.what()); return 1;} catch (const runtime_error& e) { println(cerr, "{}", e.what()); return 1;}Conveniently, invalid_argument and runtime_error are both derived classes of exception, so you can replace the two catch statements with a single catch statement for exception:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (const exception& e) { println(cerr, "{}", e.what()); return 1;}The catch statement for an exception reference matches any derived classes of exception, including both invalid_argument and runtime_error. Note that the higher in the exception hierarchy you catch exceptions, the less specific your error handling can be. You should generally catch exceptions at as specific a level as possible.

When you catch exceptions polymorphically, make sure to catch them by reference! If you catch exceptions by value, you can encounter slicing, in which case you lose information from the object. See Chapter 10 for details on slicing.

When more than one catch clause is used, the catch clauses are matched in syntactic order as they appear in your code; the first one that matches wins. If one catch is more inclusive than a later one, it will match first, and the more restrictive one, which comes later, will never be executed. Therefore, you should place your catch clauses from most restrictive to least restrictive in order. For example, suppose that you want to catch invalid_argument from readIntegerFile() explicitly, but you also want to leave the generic exception handler for any other exceptions. The correct way to do so is like this:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (const invalid_argument& e) { // List the derived class first. // Take some special action for invalid filenames.} catch (const exception& e) { // Now list exception. println(cerr, "{}", e.what()); return 1;}The first catch statement catches invalid_argument exceptions, and the second catches any other exceptions of type exception. However, if you reverse the order of the catch statements, you don’t get the same result:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (const exception& e) { // BUG: catching base class first! println(cerr, "{}", e.what()); return 1;} catch (const invalid_argument& e) { // Take some special action for invalid filenames.}With this order, any exception of a class that derives from exception is caught by the first catch statement; the second catch will never be reached. Some compilers issue a warning in this case, but you shouldn’t count on it.

Writing Your Own Exception Classes

Section titled “Writing Your Own Exception Classes”There are two advantages to writing your own exception classes:

- The number of exceptions in the C++ Standard Library is limited. Instead of using an exception class with a generic name, such as

runtime_error, you can create classes with names that are more meaningful for the particular errors in your program. - You can add your own information to these exceptions. Most exceptions in the standard hierarchy allow you to set only an error string. You might want to pass different information in the exception.

It’s recommended that all the exception classes that you write inherit directly or indirectly from the standard exception class. If everyone on your project follows that rule, you know that every exception in the program will be derived from exception (assuming that you aren’t using third-party libraries that break this rule). This guideline makes exception handling via polymorphism significantly easier.

Let’s look at an example. invalid_argument and runtime_error don’t do a good job at capturing the file opening and reading errors in readIntegerFile(). You can define your own error hierarchy for file errors, starting with a generic FileError class:

class FileError : public exception{ public: explicit FileError(string filename) : m_filename { move(filename) } {} const char* what() const noexcept override { return m_message.c_str(); } virtual const string& getFilename() const noexcept { return m_filename; } protected: virtual void setMessage(string message) { m_message = move(message); } private: string m_filename; string m_message;};As a good programming citizen, you make FileError a part of the standard exception hierarchy. It seems appropriate to integrate it as a child of exception. When you derive from exception, you can override the what() member function, which has the prototype shown and which must return a const char* string that is valid until the object is destroyed. In the case of FileError, this string comes from the m_message data member. Derived classes of FileError can set the message using the protected setMessage() member function. The generic FileError class also contains a filename and a public accessor for that filename.

The first exceptional situation in readIntegerFile() occurs when the file cannot be opened. Thus, you might want to write a FileOpenError exception derived from FileError:

class FileOpenError : public FileError{ public: explicit FileOpenError(string filename) : FileError { move(filename) } { setMessage(format("Unable to open {}.", getFilename())); }};The FileOpenError exception calls setMessage() to change the m_message string to represent the file-opening error. Note that in the body of the constructor, getFilename() is used to get the filename. The filename parameter cannot be used for this as the ctor-initializer has moved filename in the call to the FileError constructor. As you know, after a move operation, you shouldn’t use an object any longer.

The second exceptional situation in readIntegerFile() occurs if the file cannot be read properly. It might be useful for this exception to include the line number where the error occurred, as well as the filename in the error message string returned from what(). Here is a FileReadError exception derived from FileError:

class FileReadError : public FileError{ public: explicit FileReadError(string filename, size_t lineNumber) : FileError { move(filename) }, m_lineNumber { lineNumber } { setMessage(format("Error reading {}, line {}.", getFilename(), lineNumber)); }

virtual size_t getLineNumber() const noexcept { return m_lineNumber; } private: size_t m_lineNumber { 0 };};Of course, to set the line number properly, readIntegerFile() needs to be modified to track the number of lines read instead of just reading integers directly. Here is a new readIntegerFile() function that uses the new exceptions:

vector<int> readIntegerFile(const string& filename){ ifstream inputStream { filename }; if (inputStream.fail()) { // We failed to open the file: throw an exception. throw FileOpenError { filename }; }

vector<int> integers; size_t lineNumber { 0 }; while (!inputStream.eof()) { // Read one line from the file. string line; getline(inputStream, line); ++lineNumber;

// Create a string stream out of the line. istringstream lineStream { line };

// Read the integers one-by-one and add them to the vector. int temp; while (lineStream >> temp) { integers.push_back(temp); }

if (!lineStream.eof()) { // We did not reach the end of the string stream. // This means that some error occurred while reading this line. // Throw an exception. throw FileReadError { filename, lineNumber }; } }

return integers;}Now, code that calls readIntegerFile() can use polymorphism to catch exceptions of type FileError like this:

try { myInts = readIntegerFile(filename);} catch (const FileError& e) { println(cerr, "{}", e.what()); return 1;}There is one caveat when writing classes whose objects will be used as exceptions. When a piece of code throws an exception, the object or value thrown is moved or copied, using either the move constructor or the copy constructor. Thus, if you write a class whose objects will be thrown as exceptions, you must make sure those objects are copyable and/or moveable. This means that if you have dynamically allocated memory in your exception class, your class must have a destructor, but also a copy constructor and copy assignment operator and/or a move constructor and move assignment operator, see Chapter 9, “Mastering Classes and Objects.”

Objects thrown as exceptions are always moved or copied at least once.

It is possible for exceptions to be copied more than once, but only if you catch the exception by value instead of by reference.

Nested Exceptions

Section titled “Nested Exceptions”It could happen that during handling of a first exception, a second exceptional situation is triggered that requires a second exception to be thrown. Unfortunately, when you throw the second exception, all information about the first exception that you are currently trying to handle will be lost. The solution provided by C++ for this problem is called nested exceptions, which allow you to nest a caught exception in the context of a new exception. This can also be useful if you call a function in a third-party library that throws an exception of a certain type, A, but you only want exceptions of another type, B, in your code. In such a case, you catch all exceptions from the library and nest them in an exception of type B.

You use std::throw_with_nested() to throw an exception with another exception nested inside it. A catch handler for this new exception can use a dynamic_cast() to get access to the std::nested_exception representing the first exception. The upcoming example demonstrates this. It first defines a MyException class, which derives from exception and accepts a string in its constructor:

class MyException : public exception{ public: explicit MyException(string message) : m_message { move(message) } {} const char* what() const noexcept override { return m_message.c_str(); } private: string m_message;};The following doSomething() function throws a runtime_error that is immediately caught in a catch handler. The catch handler writes a message and then uses the throw_with_nested() function to throw a second exception that has the first one nested inside it. Note that nesting the exception happens automatically:

void doSomething(){ try { throw runtime_error { "A runtime_error exception" }; } catch (const runtime_error& e) { println("doSomething() caught a runtime_error"); println("doSomething() throwing MyException"); throw_with_nested( MyException { "MyException with nested runtime_error" }); }}throw_with_nested() works by throwing an unnamed new compiler-generated type that derives from both nested_exception and, in this example, from MyException. Hence, it’s another example of useful multiple inheritance in C++. The default constructor of the nested_exception base class automatically captures the exception currently being handled by calling std::current_exception() and stores it in an std::exception_ptr. An exception_ptr is a pointer-like type capable of storing either a null pointer or a pointer to an exception object that was thrown and captured with current_exception(). Instances of exception_ptr can be passed to functions (usually by value) and across different threads.

Finally, the following code snippet demonstrates how to handle an exception with a nested exception. The code calls doSomething() and has one catch handler for exceptions of type MyException. When it catches such an exception, it writes a message and then uses a dynamic_cast() to get access to the nested exception. If there is no nested exception inside, the result will be a null pointer. If there is a nested exception inside, the rethrow_nested() member function on the nested_exception is called. This causes the nested exception to be rethrown, which you can then catch in another try/catch block.

try { doSomething();} catch (const MyException& e) { println("main() caught MyException: {}", e.what());

const auto* nested { dynamic_cast<const nested_exception*>(&e) }; if (nested) { try { nested->rethrow_nested(); } catch (const runtime_error& e) { // Handle nested exception. println(" Nested exception: {}", e.what()); } }}The output is as follows:

doSomething() caught a runtime_errordoSomething() throwing MyExceptionmain() caught MyException: MyException with nested runtime_error Nested exception: A runtime_error exceptionThis code uses a dynamic_cast() to check for a nested exception. Because you always have to perform such a dynamic_cast() if you want to check for a nested exception, the standard provides a helper function called std::rethrow_if_nested() that does it for you. This helper function can be used as follows:

try { doSomething();} catch (const MyException& e) { println("main() caught MyException: {}", e.what()); try { rethrow_if_nested(e); } catch (const runtime_error& e) { // Handle nested exception. println(" Nested exception: {}", e.what()); }}throw_with_nested(), nested_exception, rethrow_if_nested(), current_exception(), and exception_ptr are all defined in <exception>.

RETHROWING EXCEPTIONS

Section titled “RETHROWING EXCEPTIONS”The throw keyword can also be used to rethrow the current exception without copying it, as in the following example:

void g() { throw invalid_argument { "Some exception" }; }

void f(){ try { g(); } catch (const invalid_argument& e) { println("caught in f(): {}", e.what()); throw; // rethrow }}

int main(){ try { f(); } catch (const invalid_argument& e) { println("caught in main(): {}", e.what()); }}This example produces the following output:

caught in f(): Some exceptioncaught in main(): Some exceptionYou might think you could rethrow a caught exception e with throw e;. However, that’s wrong, because it can cause slicing of your exception object. For example, suppose f() is modified to catch std::exceptions, and main() is modified to catch both exception and invalid_argument exceptions:

void g() { throw invalid_argument { "Some exception" }; }

void f(){ try { g(); } catch (const exception& e) { println("caught in f(): {}", e.what()); throw; // rethrow }}

int main(){ try { f(); } catch (const invalid_argument& e) { println("invalid_argument caught in main(): {}", e.what()); } catch (const exception& e) { println("exception caught in main(): {}", e.what()); }}Remember that invalid_argument derives from exception, hence it must be caught first. The output of this code is as you would expect, shown here:

caught in f(): Some exceptioninvalid_argument caught in main(): Some exceptionNow, try replacing the throw; statement in f() with throw e;. The output then becomes as follows:

caught in f(): Some exceptionexception caught in main(): Some exceptionmain() seems to be catching an exception object, instead of an invalid_argument object. That’s because the throw e; statement causes slicing, reducing the invalid_argument to an exception.

Always use throw; to rethrow an exception. Never do something like throw e; to rethrow a caught exception e!

STACK UNWINDING AND CLEANUP

Section titled “STACK UNWINDING AND CLEANUP”When a piece of code throws an exception, it searches for a catch handler on the stack. This catch handler could be zero or more function calls up the stack of execution. When one is found, the stack is stripped back to the stack level that defines the catch handler by unwinding all intermediate stack frames. Stack unwinding means that the destructors for all locally scoped variables are called, and all code remaining in each function past the current point of execution is skipped.

During stack unwinding, pointer variables are obviously not freed, and other cleanup is not performed either. This behavior can present problems. For example, the following code causes a memory leak:

void funcOne();void funcTwo();

int main(){ try { funcOne(); } catch (const exception& e) { println(cerr, "Exception caught!"); return 1; }}

void funcOne(){ string str1; string* str2 { new string {} }; funcTwo(); delete str2;}

void funcTwo(){ ifstream fileStream; fileStream.open("filename"); throw exception {}; fileStream.close();}When funcTwo() throws an exception, the closest exception handler is in main(). Control then jumps immediately from this line in funcTwo(),

throw exception {};to this line in main():

println(cerr, "Exception caught!");In funcTwo(), control remains at the line that threw the exception, so this subsequent line never gets a chance to run:

fileStream.close();However, luckily for you, the ifstream destructor is called because fileStream is a local variable on the stack. The ifstream destructor closes the file for you, so there is no resource leak here. If you had dynamically allocated fileStream, it would not be destroyed, and the file would not be closed.

In funcOne(), control is at the call to funcTwo(), so this subsequent line never gets a chance to run:

delete str2;In this case, there really is a memory leak. Stack unwinding does not automatically call delete on str2 for you. On the other hand, str1 is destroyed properly because it is a local variable on the stack. Stack unwinding destroys all local variables correctly.

Careless exception handling can lead to memory and resource leaks.

This is one reason why you should never mix older C models of allocation (even if you are calling new so it looks like C++) with modern programming methodologies like exceptions. In C++, this situation should be handled by using stack-based allocations or, if that is not possible, by one of the techniques discussed in the upcoming two sections.

Use Smart Pointers

Section titled “Use Smart Pointers”If stack-based allocation is not possible, then use smart pointers. They allow you to write code that automatically prevents memory or resource leaks during exception handling. Whenever a smart pointer object is destroyed, it frees the underlying resource. Here is a modified funcOne() implementation using a unique_ptr smart pointer, defined in <memory>, and introduced in Chapter 7, “Memory Management”:

void funcOne(){ string str1; auto str2 { make_unique<string>("hello") }; funcTwo();}The str2 pointer will automatically be deleted when you return from funcOne() or when an exception is thrown.

Of course, you should only allocate something dynamically if you have a good reason to do so. For example, in funcOne(), there is no good reason to make str2 a dynamically allocated string. It should just be a stack-based string variable. It’s merely shown here as an artificial example of the consequences of throwing exceptions.

Catch, Cleanup, and Rethrow

Section titled “Catch, Cleanup, and Rethrow”Another technique for avoiding memory and resource leaks is for each function to catch any possible exceptions, perform necessary cleanup work, and rethrow the exception for the function higher up the stack to handle. Here is a revised funcOne() with this technique:

void funcOne(){ string str1; string* str2 { new string {} }; try { funcTwo(); } catch (…) { delete str2; throw; // Rethrow the exception. } delete str2;}This function wraps the call to funcTwo() with an exception handler that performs the cleanup (calls delete on str2) and then rethrows the exception. The keyword throw by itself rethrows whatever exception was caught most recently. Note that the catch statement uses the … syntax to catch all exceptions.

This method works fine but is messy and error prone. In particular, note that there are now two identical lines that call delete on str2: one while handling the exception and one when the function exits normally.

The preferred solution is to use stack-based allocation, or, if not possible, to use smart pointers or other RAII classes instead of the catch, cleanup, and rethrow technique.

SOURCE LOCATION

Section titled “SOURCE LOCATION”Before C++20, you could use the following preprocessor macros to get information about a location in your source code:

| MACRO | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| __FILE__ | Replaced with the current source code filename |

| __LINE__ | Replaced with the current line number in the source code |

Additionally, every function has a locally defined static character array called __func__ containing the name of the function.

Since C++20, a proper object-oriented replacement for __func__ and these C-style preprocessor macros is available in the form of an std::source:location class, defined in <source:location>. An instance of source:location has the following public accessors:

| ACCESSOR | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| file_name() | Contains the current source code filename |

| function_name() | Contains the current function name, if the current position is inside a function |

| line() | Contains the current line number in the source code |

| column() | Contains the current column number in the source code |

A static member function current() is provided that creates a source:location instance based on the location in the source code where the member function is called.

Source Location for Logging

Section titled “Source Location for Logging”The source:location class is useful for logging purposes. Previously, logging often involved writing C-style macros to automatically gather the current file name, function name, and line number, so they could be included in the log output. Now, with source:location, you can write a pure C++ function to perform your logging and to automatically collect the location data you require. A nice trick to do this is defining a logMessage() function as follows. This time, the code is prefixed with line numbers to better explain what is happening.

5. void logMessage(string_view message, 6. const source:location& location = source:location::current()) 7. { 8. println("{}({}): {}: {}", location.file_name(), 9. location.line(), location.function_name(), message);10. }11.12. void foo()13. {14. logMessage("Starting execution of foo().");15. }16.17. int main()18. {19. foo();20. }The second parameter of logMessage() is a source:location with the result of the static member function current() as default value. The trick here is that the call to current() does not happen on line 6, but actually at the location where logMessage() is called, which is line 14, and that’s exactly the location you are interested in.

When executing this program with Microsoft Visual C++, the output is as follows:

./01_Logging.cpp(14): void __cdecl foo(void): Starting execution of foo().Line 14 indeed corresponds to the line calling logMessage(). The exact name of the function, void __cdecl foo(void) in this case, is compiler dependent.

Automatically Embed a Source Location in Custom Exceptions

Section titled “Automatically Embed a Source Location in Custom Exceptions”Another interesting use case for source:location is in your own exception classes to automatically store the location where an exception was thrown. Here’s an example:

class MyException : public exception{ public: explicit MyException(string message, source:location location = source:location::current()) : m_message { move(message) } , m_location { move(location) } { }

const char* what() const noexcept override { return m_message.c_str(); } virtual const source:location& where() const noexcept{ return m_location; } private: string m_message; source:location m_location;};

void doSomething(){ throw MyException { "Throwing MyException." };}

int main(){ try { doSomething(); } catch (const MyException& e) { const auto& location { e.where() }; println(cerr, "Caught: '{}' at line {} in {}.", e.what(), location.line(), location.function_name()); }}The output with Microsoft Visual C++ is similar to the following:

Caught: 'Throwing MyException.' at line 26 in void __cdecl doSomething(void).

Section titled “ STACK TRACE”Whenever a function A() calls another function B(), the arguments to be passed to B() are recorded and information about where to return to when the function is finished is recorded as well. The execution of B() can again call another function C() and so on. All this information is recorded in frames on a stack trace, also known as a call stack. For each function call, a new frame is added to the stack trace. When the execution of the function is finished, its frame is removed from the stack trace. At any given moment in the execution of your program, the stack trace tells you exactly through which function calls you arrived in the currently executing function. Information like this is vital for finding and fixing bugs in your program. Chapter 31, “Conquering Debugging,” discusses debugging in detail. This section discusses the functionality provided by the Standard Library to work with stack traces, as well as how this can be very useful in combination with custom exceptions. Everything discussed in this section is new since C++23.

The Stack Trace Library

Section titled “The Stack Trace Library”The stack trace library is defined in <stacktrace>. You can retrieve a stack trace at any moment in time using the static member function std::stacktrace::current(). You can pass an integer to current() if you want to skip a certain number of top frames. An example of this is given in the next section. Once you have a stack trace, you can easily print it to the console using print() or println(). You can also convert a stack trace to a string using std::to_string(). Here is an example, with the stack trace–related statements highlighted:

void handleStackTrace(const stacktrace& trace){ println(" Stack trace information:"); println(" There are {} frames in the stack trace.", trace.size()); println(" Here are all the frames:"); println("---------------------------------------------------------"); println("{}", trace); // If the above statement doesn't work yet, you can use the following: //println("{}", to_string(trace)); println("---------------------------------------------------------");}

void C(){ println("Entered C()."); handleStackTrace(stacktrace::current());}

void B() { println("Entered B()."); C(); }void A() { println("Entered A()."); B(); }

int main(){ A();}Compiled with Microsoft Visual C++ and running on Windows, the output resembles the following. Long pathnames have been trimmed to prevent wrapping of lines. The 01_stacktrace.cpp file is our code. The exe_common.inl and exe_main.cpp files belong to the Visual C++ runtime. The final two frames, kernel32 and ntdll, are part of the Windows kernel. Function names are highlighted for readability.

Entered A().Entered B().Entered C(). Stack trace information: There are 10 frames in the stack trace. Here are all the frames:---------------------------------------------------------0> D:\…\01_stacktrace.cpp(20): TestApp!C+0x771> D:\…\01_stacktrace.cpp(27): TestApp!B+0x612> D:\…\01_stacktrace.cpp(33): TestApp!A+0x613> D:\…\01_stacktrace.cpp(38): TestApp!main+0x204> D:\…\exe_common.inl(79): TestApp!invoke_main+0x395> D:\…\exe_common.inl(288): TestApp!__scrt_common_main_seh+0x12E6> D:\…\exe_common.inl(331): TestApp!__scrt_common_main+0xE7> D:\…\exe_main.cpp(17): TestApp!mainCRTStartup+0xE8> KERNEL32!BaseThreadInitThunk+0x1D9> ntdll!RtlUserThreadStart+0x28---------------------------------------------------------You can iterate over the individual frames of a stack trace and query for information of each frame. A frame is represented by the std::stacktrace:entry class, which supports the following member functions:

description(): Returns the description of the framesource:file()andsource:line(): The name of the source file and the line number within it that contains the statement represented by the frame

For example, the following implementation of handleStackTrace() doesn’t just print the entire stack trace all at once but iterates over the individual frames and prints out only the description of each.

void handleStackTrace(const stacktrace& trace){ println(" Stack trace information:"); println(" There are {} frames in the stack trace.", trace.size()); println(" Here are the descriptions of all the frames:"); for (unsigned index { 0 }; auto&& frame : trace) { println(" {} -> {}", index++, frame.description()); }}The output now is as follows:

Entered A().Entered B().Entered C(). Stack trace information: There are 10 frames in the stack trace. Here are the descriptions of all the frames: 0 -> TestApp!C+0x77 1 -> TestApp!B+0x61 2 -> TestApp!A+0x61 3 -> TestApp!main+0x20 4 -> TestApp!invoke_main+0x39 … <snip> …Automatically Embed a Stack Trace in Custom Exceptions

Section titled “Automatically Embed a Stack Trace in Custom Exceptions”We can extend the MyException class from an earlier section on source:location to include a stack trace in addition to the source location.

class MyException : public exception{ public: explicit MyException(string message, source:location location = source:location::current()) : m_message { move(message) } , m_location { move(location) } , m_stackTrace { stacktrace::current(1) } // 1 means skip top frame. { }

const char* what() const noexcept override { return m_message.c_str(); } virtual const source:location& where() const noexcept{ return m_location; } virtual const stacktrace& how() const noexcept { return m_stackTrace; } private: string m_message; source:location m_location; stacktrace m_stackTrace;};Note that the constructor passes 1 to stacktrace::current() to skip the top frame of the stack trace. This top frame would be the constructor of MyException, which we are not interested in. We’re interested only in the stack trace leading up to the construction of this MyException instance. This new exception class can be tested as follows:

void doSomething(){ throw MyException { "Throwing MyException." };}

int main(){ try { doSomething(); } catch (const MyException& e) { // Print exception description + location where exception was raised. const auto& location { e.where() }; println(cerr, "Caught: '{}' at line {} in {}.", e.what(), location.line(), location.function_name());

// Print the stack trace at the point where the exception was raised. println(cerr, " Stack trace:"); for (unsigned index { 0 }; auto&& frame : e.how()) { const string& fileName { frame.source:file() }; println(cerr, " {}> {}, {}({})", index++, frame.description(), (fileName.empty() ? "n/a" : fileName), frame.source:line()); } }}When compiling with Microsoft Visual C++ and running on Windows, the output resembles the following. Only the top two relevant entries of the stack trace are shown. The stack entries that are inside the Visual C++ runtime or inside Windows itself are omitted for brevity.

Caught: 'Throwing MyException.' at line 30 in void __cdecl doSomething(void). Stack trace: 0 > TestApp!doSomething+0xD2, D:\…\03_CustomExceptionWithStackTrace.cpp(30) 1 > TestApp!main+0x4D, D:\…\03_CustomExceptionWithStackTrace.cpp(36) … <snip> ...COMMON ERROR-HANDLING ISSUES

Section titled “COMMON ERROR-HANDLING ISSUES”Whether or not you use exceptions in your programs is up to you and your colleagues. However, you are strongly encouraged to formalize an error-handling plan for your programs, regardless of your use of exceptions. If you use exceptions, it is generally easier to come up with a unified error-handling scheme, but it is not impossible without exceptions. The most important aspect of a good plan is uniformity of error handling throughout all the modules of the program. Make sure that every programmer on the project understands and follows the error-handling rules.

This section discusses the most common error-handling issues in the context of exceptions, but the issues are also relevant to programs that do not use exceptions.

Memory Allocation Errors

Section titled “Memory Allocation Errors”Despite that all the examples so far in this book have ignored the possibility, memory allocation can fail. On current 64-bit platforms, this will almost never happen, but on mobile or legacy systems, memory allocation can fail. On such systems, you must account for memory allocation failures. C++ provides several different ways to handle memory errors.

The default behaviors of new and new[] are to throw an exception of type bad_alloc, defined in <new>, if they cannot allocate memory. Your code could catch these exceptions and handle them appropriately.

It’s not realistic to wrap all your calls to new and new[] with a try/catch, but at least you should do so when you are trying to allocate a big block of memory. The following example demonstrates how to catch memory allocation exceptions:

int* ptr { nullptr };size_t integerCount { numeric_limits<size_t>::max() };println("Trying to allocate memory for {} integers.", integerCount);try { ptr = new int[integerCount];} catch (const bad_alloc& e) { auto location { source:location::current() }; println(cerr, "{}({}): Unable to allocate memory: {}", location.file_name(), location.line(), e.what()); // Handle memory allocation failure. return;}// Proceed with function that assumes memory has been allocated.Note that this code uses source:location to include the name of the file and the current line number in the error message. This makes debugging easier.

You could, of course, bulk handle many possible new failures with a single try/catch block at a higher point in the program, if that works for your program.

Another point to consider is that logging an error might try to allocate memory. If new fails, there might not be enough memory left even to log the error message.

Non-throwing new

Section titled “Non-throwing new”If you don’t like exceptions, you can revert to the old C model in which memory allocation routines return a null pointer if they cannot allocate memory. C++ provides nothrow overloads of new and new[], which return nullptr instead of throwing an exception if they fail to allocate memory. This is done by using the syntax new(nothrow) instead of new, as shown in the following example:

int* ptr { new(nothrow) int[integerCount] };if (ptr == nullptr) { auto location { source:location::current() }; println(cerr, "{}({}): Unable to allocate memory!", location.file_name(), location.line()); // Handle memory allocation failure. return;}// Proceed with function that assumes memory has been allocated.Customizing Memory Allocation Failure Behavior

Section titled “Customizing Memory Allocation Failure Behavior”C++ allows you to specify a new handler callback function. By default, there is no new handler, so new and new[] just throw bad_alloc exceptions. However, if there is a new handler, the memory allocation routine calls the new handler upon memory allocation failure instead of throwing an exception. If the new handler returns, the memory allocation routine attempts to allocate memory again, calling the new handler again if it fails. This cycle could become an infinite loop unless your new handler changes the situation with one of three alternatives. Practically speaking, some of the options are better than others.

- Make more memory available. One trick to expose space is to allocate a large chunk of memory at program start-up and then to free it in the new handler. A practical example is when you hit an allocation error and you need to save the user state so no work gets lost. The key is to allocate a block of memory at program start-up large enough to allow a complete document save operation. When the new handler is triggered, you free this block, save the document, restart the application, and let it reload the saved document.

- Throw an exception. The C++ standard mandates that if you throw an exception from your new handler, it must be a

bad_allocexception or an exception derived frombad_alloc. Here are some examples:- Write and throw a

document_recovery_allocexception, deriving frombad_alloc. This exception can be caught somewhere in your application to trigger the document save operation and restart of the application. - Write and throw a

please_terminate_meexception, deriving frombad_alloc. In your top-level function—for example,main()—you catch this exception and handle it by returning from the top-level function. It’s recommended to terminate a program by returning from the top-level function, instead of by calling a function such asexit().

- Write and throw a

- Set a different new handler. Theoretically, you could have a series of new handlers, each of which tries to create memory and sets a different new handler if it fails. However, such a scenario is usually more complicated than useful.

If you don’t do one of these things in your new handler, any memory allocation failure will cause an infinite loop.

If there are some memory allocations that can fail but you don’t want your new handler to be called, you can simply set the new handler back to its default of nullptr temporarily before calling new in such cases.

You set the new handler with a call to set_new_handler(), declared in <new>. Here is an example of a new handler that logs an error message and throws an exception:

class please_terminate_me : public bad_alloc { };

void myNewHandler(){ println(cerr, "Unable to allocate memory."); throw please_terminate_me {};}The new handler must take no arguments and return no value. This new handler throws a please_terminate_me exception, as suggested in the preceding list. You can activate this new handler like this:

int main(){ try { // Set the new new_handler and save the old one. new_handler oldHandler { set_new_handler(myNewHandler) };

// Generate allocation error. size_t numInts { numeric_limits<size_t>::max() }; int* ptr { new int[numInts] };

// Reset the old new_handler. set_new_handler(oldHandler); } catch (const please_terminate_me&) { auto location { source:location::current() }; println(cerr, "{}({}): Terminating program.", location.file_name(), location.line()); return 1; }}new_handler is a type alias for the type of function pointer that set_new_handler() takes.

Errors in Constructors

Section titled “Errors in Constructors”Before C++ programmers discover exceptions, they are often stymied by error handling and constructors. What if a constructor fails to construct the object properly? Constructors don’t have a return value, so the standard pre-exception error-handling mechanism doesn’t work. Without exceptions, the best you can do is to set a flag in the object specifying that it is not constructed properly. You can provide a member function, with a name like checkConstructionStatus(), which returns the value of that flag, and hope that clients remember to call this member function on the object after constructing it.

Exceptions provide a much better solution. You can throw an exception from a constructor, even though you can’t return a value1. With exceptions, you can easily tell clients whether construction of an object succeeded. However, there is one major problem: if an exception leaves a constructor, the destructor for that object will never be called! Thus, you must be careful to clean up any resources and free any allocated memory in constructors before allowing exceptions to leave the constructor.

This section describes a Matrix class template as an example in which the constructor correctly handles exceptions. Note that this example is using a raw pointer called m_matrix to demonstrate the problems. In production-quality code, you should avoid using raw pointers, for example, by using a Standard Library container! The definition of the Matrix class template looks like this:

export template <typename T>class Matrix final{ public: explicit Matrix(std::size_t width, std::size_t height); ˜Matrix(); // Copy/move ctors and copy/move assignment operators deleted (omitted). private: void cleanup();

std::size_t m_width { 0 }; std::size_t m_height { 0 }; T** m_matrix { nullptr };};The implementation of the Matrix class is as follows. The first call to new is not protected with a try/catch block. It doesn’t matter if the first new throws an exception because the constructor hasn’t allocated anything else yet that needs freeing. If any of the subsequent new calls throw an exception, though, the constructor must clean up all of the memory already allocated. The constructor doesn’t know what exceptions the T constructors themselves might throw, so it catches all exceptions via … and then nests the caught exception inside a bad_alloc exception. The array allocated with the first call to new is zero-initialized using the {} syntax; that is, each element will be nullptr. This makes the cleanup() member function easier, because it is allowed to call delete on a nullptr.

template <typename T>Matrix<T>::Matrix(std::size_t width, std::size_t height){ m_matrix = new T*[width] {}; // Array is zero-initialized!

// Don't initialize the m_width and m_height members in the ctor- // initializer. These should only be initialized when the above // m_matrix allocation succeeds! m_width = width; m_height = height;

try { for (std::size_t i { 0 }; i < width; ++i) { m_matrix[i] = new T[height]; } } catch (…) { std::println(std::cerr, "Exception caught in constructor, cleaning up…"); cleanup(); // Nest any caught exception inside a bad_alloc exception. std::throw_with_nested(std::bad_alloc {}); }}

template <typename T>Matrix<T>::˜Matrix(){ cleanup();}

template <typename T>void Matrix<T>::cleanup(){ for (std::size_t i { 0 }; i < m_width; ++i) { delete[] m_matrix[i]; } delete[] m_matrix; m_matrix = nullptr; m_width = m_height = 0;}Remember, if an exception leaves a constructor, the destructor for that object will never be called!

The Matrix class template can be tested as follows. Catching the bad_alloc exception in main() is omitted for brevity.

class Element{ // Kept to a bare minimum, but in practice, this Element class // could throw exceptions in its constructor. private: int m_value;};

int main(){ Matrix<Element> m { 10, 10 };}You might be wondering what happens when you add inheritance into the mix. Base class constructors run before derived class constructors. If a derived class constructor throws an exception, C++ will execute the destructor of the fully constructed base classes.

Function-Try-Blocks for Constructors

Section titled “Function-Try-Blocks for Constructors”The exception mechanism, as discussed up to now in this chapter, is perfect for handling exceptions within functions. But how should you handle exceptions thrown from inside a ctor-initializer of a constructor? This section explains a feature called function-try-blocks, which are capable of catching those exceptions. Function-try-blocks work for normal functions as well as for constructors. This section focuses on the use with constructors. Most C++ programmers, even experienced C++ programmers, don’t know of the existence of this feature, even though it was introduced a long time ago.

The following piece of pseudo-code shows the basic syntax for a function-try-block for a constructor:

MyClass::MyClass()try : <ctor-initializer>{ /* … constructor body … */}catch (const exception& e){ /* … */}As you can see, the try keyword should be right before the start of the ctor-initializer. The catch statements should be after the closing brace for the constructor, actually putting them outside the constructor body. There are a number of restrictions and guidelines that you should keep in mind when using function-try-blocks with constructors:

- The

catchstatements catch any exception thrown either directly or indirectly by the ctor-initializer or by the constructor body. - The

catchstatements have to rethrow the current exception or throw a new exception. If acatchstatement doesn’t do this, the runtime automatically rethrows the current exception. - The

catchstatements can access arguments passed to the constructor. - When a

catchstatement catches an exception in a function-try-block, all fully constructed base classes and members of the object are destroyed before execution of thecatchstatement starts. - Inside

catchstatements you should not access data members that are objects because these are destroyed prior to executing thecatchstatements (see the previous bullet). However, if your object contains non-class data members—for example, raw pointers—you can access them if they have been initialized before the exception was thrown. If you have such raw, also called naked, resources, you have to take care of them by freeing them in thecatchstatements, as the upcoming example demonstrates. - The catch statements in a function-try-block for a constructor cannot use the return keyword.

Based on this list of limitations, function-try-blocks for constructors are useful only in a limited number of situations:

- To convert an exception thrown by the ctor-initializer to another exception

- To log a message to a log file

- To free raw resources that have been allocated in the ctor-initializer prior to the exception being thrown

The following example demonstrates how to use function-try-blocks. The code defines a class called SubObject. It has only one constructor, which throws an exception of type runtime_error:

class SubObject{ public: explicit SubObject(int i) { throw runtime_error { "Exception by SubObject ctor" }; }};Next, the MyClass class has a data member of type int* and another one of type SubObject:

class MyClass{ public: MyClass(); private: int* m_data { nullptr }; SubObject m_subObject;};The SubObject class does not have a default constructor. This means you need to initialize m_subObject in the MyClass ctor-initializer. The constructor of MyClass uses a function-try-block to catch exceptions thrown in its ctor-initializer as follows: