Understanding Iterators and the Ranges Library

Chapter 16, “Overview of the C++ Standard Library,” introduces the Standard Library, describes its basic philosophy, and provides an overview of the provided functionality. This chapter begins a more-in-depth tour of the Standard Library by covering the ideas behind iterators used throughout a big part of the library. It also discusses the available stream iterators and iterator adapters. The second part of the chapter discusses the ranges library, a powerful library that allows for more functional-style programming: you write code that specifies what you want to accomplish instead of how.

ITERATORS

Section titled “ITERATORS”The Standard Library uses the iterator pattern to provide a generic abstraction for accessing the elements of a container. Each container provides a container-specific iterator, which is a glorified pointer that knows how to iterate over the elements of that specific container, i.e., an iterator supports traversing the elements of a container. The different iterators for the various containers adhere to standard interfaces defined by the C++ standard. Thus, even though the containers provide different functionality, the iterators present a common interface to code that wants to work with elements of the containers. This results in code that is easier to read and write, less error-prone (e.g., iterators are easier to use correctly compared to pointer arithmetic), more efficient (especially for containers that do not support random access, such as std::list and forward_list; see Chapter 16), and easier to debug (e.g., iterators could perform bounds checking in debug builds of your code). Additionally, when using iterators to iterate over the contents of a container, the underlying implementation of the container could change completely without any impact on your iterator-based code.

You can think of an iterator as a pointer to a specific element of the container. Like pointers to elements in an array, iterators can move to the next element with operator++. Similarly, you can usually use operator* and operator-> on the iterator to access the actual element or field of the element. Some iterators allow comparison with operator== and operator!=, and support operator-- for moving to previous elements.

All iterators must be copy constructible, copy assignable, and destructible. Lvalues of iterators must be swappable. Different containers provide iterators with slightly different additional capabilities. The standard defines six categories of iterators, as summarized in the following table:

| ITERATOR CATEGORY | OPERATIONS REQUIRED | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Input (also known as Read) | operator++, *, ->, =, ==, != copy constructor | Provides read-only access, forward only (no operator-- to move backward). Iterators can be assigned, copied, and compared for equality. |

| Output (also known as Write) | operator++, *, = copy constructor | Provides write-only access, forward only. Iterators can be assigned, but cannot be compared for equality. Specific to output iterators is that you can do *iter = value. Note the absence of operator->. Provides both prefix and postfix operator++. |

| Forward | Capabilities of input iterators, plus default constructor | Provides read access, forward only. Iterators can be assigned, copied, and compared for equality. |

| Bidirectional | Capabilities of forward iterators, plus operator-- | Provides everything a forward iterator provides. Iterators can also move backward to a previous element. Provides both prefix and postfix operator--. |

| Random access | Bidirectional capability, plus the following: cpp operator+, -, +=, -=, <,>, <=,>=, [] | Equivalent to raw pointers: support pointer arithmetic, array index syntax, and all forms of comparison. |

| Contiguous | Random-access capability and logically adjacent elements of the container must be physically adjacent in memory | Examples of this are iterators of std::array, vector (not vector<bool>), string, and string_view. |

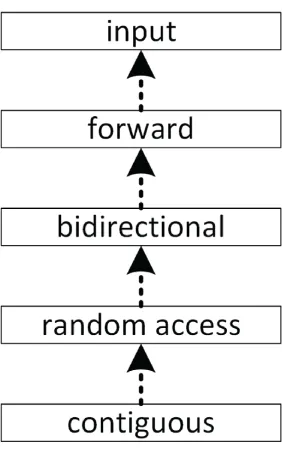

According to this table, there are six types of iterators: input, output, forward, bidirectional, random access, and contiguous. There is no formal class hierarchy of these iterators. However, one can deduce a hierarchy based on the functionality they are required to provide. Specifically, every contiguous iterator is also random access, every random-access iterator is also bidirectional, every bidirectional iterator is also forward, and every forward iterator is also input. Iterators that additionally satisfy the requirements for output iterators are called mutable iterators; otherwise, they are called constant iterators. Figure 17.1 shows such hierarchy. Dotted lines are used because the figure is not a real class hierarchy.

[^FIGURE 17.1]

The standard technique for an algorithm to specify what kind of iterators it requires is to use names similar to the following for its iterator template type parameters: InputIterator, OutputIterator, ForwardIterator, BidirectionalIterator, RandomAccessIterator, and ContiguousIterator. These names are just names: they don’t provide binding type checking. Therefore, you could, for example, try to call an algorithm expecting a RandomAccessIterator by passing a bidirectional iterator. The template cannot do type checking, so it would allow this instantiation. However, the code in the function that uses the random-access iterator capabilities would fail to compile on the bidirectional iterator. Thus, the requirement is enforced, just not where you would expect. The error message can therefore be somewhat confusing. For example, attempting to use the generic sort() algorithm, which requires a random-access iterator, on a list, which provides only a bidirectional iterator, can result in a cryptic error. The following is the error generated by Visual C++ 2022:

…\MSVC\14.37.32705\include\algorithm(8061,45): error C2676: binary '-': 'const std::_List_unchecked_iterator<std::_List_val<std::_List_simple_types<_Ty>>>' does not define this operator or a conversion to a type acceptable to the predefined operator with [ _Ty=int ]Later in this chapter, the ranges library is introduced, which comes with range-based and constrained versions of most Standard Library algorithms. These constrained algorithms have proper type constraints (see Chapter 12, “Writing Generic Code with Templates”) for their template type parameters. Hence, the compiler can provide clearer error messages if you try to execute such an algorithm on a container that provides the wrong type of iterators.

Iterators are implemented similarly to smart pointer classes in that they overload the specific desired operators. Consult Chapter 15, “Overloading C++ Operators,” for details on operator overloading.

The basic iterator operations are similar to those supported by raw pointers, so a raw pointer can be a legitimate iterator for certain containers. In fact, the vector iterator could technically be implemented as a simple raw pointer. However, as a client of the containers, you need not worry about the implementation details; you can simply use the iterator abstraction.

Getting Iterators for Containers

Section titled “Getting Iterators for Containers”Every data structure of the Standard Library that supports iterators provides public type aliases for its iterator types, called iterator and const_iterator. For example, a const iterator for a vector of ints has as type std::vector<int>::const_iterator. Containers that allow you to iterate over their elements in reverse order also provide public type aliases called reverse_iterator and const_reverse_iterator. This way, clients can use the container iterators without worrying about the actual types.

The containers also provide a member function begin() that returns an iterator referring to the first element in the container. The end() member function returns an iterator to the “past-the-end” value of the sequence of elements. That is, end() returns an iterator that is equal to the result of applying operator++ to an iterator referring to the last element in the sequence. Together, begin() and end() provide a half-open range that includes the first element but not the last. The reason for this apparent complication is to support empty ranges (containers without any elements), in which case begin() is equal to end(). The half-open range bounded by iterators begin() and end() is often written mathematically like this: [begin, end).

Additionally, the following member functions are available:

cbegin()andcend()returningconstiteratorsrbegin()andrend()returning reverse iteratorscrbegin()andcrend()returningconstreverse iterators

<iterator> also provides the following global nonmember functions to retrieve specific iterators for a container:

| FUNCTION NAME | FUNCTION SYNOPSIS |

|---|---|

begin() end() | Returns a non-const iterator to the first, and one past the last, element in a sequence |

cbegin() cend() | Returns a const iterator to the first, and one past the last, element in a sequence |

rbegin() rend() | Returns a non-const reverse iterator to the last, and one before the first, element in a sequence |

crbegin() crend() | Returns a const reverse iterator to the last, and one before the first, element in a sequence |

These nonmember functions are defined in the std namespace; however, especially when writing generic code for class and function templates, it is recommended to use these non-member functions as follows:

using std::begin;begin(…);Note that begin() is called without any namespace qualification, as this enables argument-dependent lookups (ADL).

When you specialize one of these nonmember functions for your own types, you can either put those specializations in the std namespace or put them in the same namespace as the type for which you are specializing them. The latter is recommended as this enables ADL. Thanks to ADL, you can then call your specialization without having to qualify it with any namespace, because the compiler is able to find the correct specialization in your namespace based on the types of arguments passed to the specialized function template.

By combining ADL (calling begin(…) without any namespace qualification) with the using std::begin declaration, the compiler first looks up the right overload in the namespace of the type of its argument using ADL. If the compiler cannot find an overload using ADL, it tries to find an appropriate overload in the std namespace due to the using declaration. Just calling begin() without the using declaration would only call user-defined overloads through ADL, and just calling std::begin() would only look in the std namespace.

Of course, ADL is not limited to the functions discussed in this section but can be used with any function.

Iterator Traits

Section titled “Iterator Traits”Some algorithm implementations need additional information about their iterators. For example, they might need to know the type of the elements referred to by the iterator to store temporary values, or perhaps they want to know whether the iterator is bidirectional or random access.

C++ provides a class template called iterator_traits, defined in <iterator>, that allows you to retrieve this information. You instantiate the iterator_traits class template with the iterator type of interest, and access one of five type aliases:

- value_type: The type of elements referred to

- difference:type: A type capable of representing the distance, i.e., number of elements, between two iterators

- iterator_category: The type of iterator:

input_iterator_tag,output_iterator_tag,forward_iterator_tag,bidirectional_iterator_tag,random_access_iterator_tag, orcontiguous_iterator_tag - pointer: The type of a pointer to an element

- reference: The type of a reference to an element

For example, the following function template declares a temporary variable of the type that an iterator of type IteratorType refers to. Note the use of the typename keyword in front of iterator_traits. You must specify typename explicitly whenever you access a type based on one or more template type parameters. In this case, the template type parameter IteratorType is used to access the value_type type of iterator_traits.

template <typename IteratorType>void iteratorTraitsTest(IteratorType it){ typename iterator_traits<IteratorType>::value_type temp; temp = *it; println("{}", temp);}This function can be tested with the following code:

vector v { 5 };iteratorTraitsTest(cbegin(v));With this code, the variable temp in iteratorTraitsTest() is of type int. The output is 5.

Of course, the auto keyword could be used in this example to simplify the code, but that wouldn’t show you how to use iterator_traits.

Examples

Section titled “Examples”The following example simply uses a for loop and iterators to iterate over every element in a vector and prints them to standard output:

vector values { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 };for (auto iter { cbegin(values) }; iter != cend(values); ++iter) { print("{} ", *iter);}You might be tempted to test for the end of a common range using operator<, as in iter<cend(values). That is not recommended, however. The canonical way to test for the end of a range is to use !=, as in iter!=cend(values). The reason is that the != operator works on all types of iterators, while the < operator is not supported by bidirectional and forward iterators.

A helper function can be implemented that accepts a common range of elements given as a begin and end iterator and prints all elements in that range to standard output. The input_iterator concept is used to constrain the template type parameter to input iterators.

template <input_iterator Iter>void myPrint(Iter begin, Iter end){ for (auto iter { begin }; iter != end; ++iter) { print("{} ", *iter); }}This helper function can be used as follows:

myPrint(cbegin(values), cend(values));A second example is a myFind() function template that finds a given value in a given common range. If the value is not found, the end iterator of the range is returned. Note the special type of the value parameter. It uses iterator_traits to get the type of the values to which the given iterators point to.

template <input_iterator Iter>auto myFind(Iter begin, Iter end, const typename iterator_traits<Iter>::value_type& value){ for (auto iter { begin }; iter != end; ++iter) { if (*iter == value) { return iter; } } return end;}This function template can be used as follows. The std::distance() function is used to compute the distance between two iterators of a container.

vector values { 11, 22, 33, 44 };auto result { myFind(cbegin(values), cend(values), 22) };if (result != cend(values)) { println("Found value at position {}", distance(cbegin(values), result));}More examples of using iterators are given throughout this and subsequent chapters.

Function Dispatching Using Iterator Traits

Section titled “Function Dispatching Using Iterator Traits”The Standard Library provides the std::advance(iter, n) function to advance a given iterator, iter, by n positions. This function works on all types of iterators. For random-access iterators, it simply does iter += n. For other iterators, it does ++iter or --iter in a loop n times, depending on whether n is positive or negative. You might wonder how such behavior is implemented. It can be implemented using function dispatching. Based on the iterator category, the request is dispatched to a specific helper function. Here’s a simplified implementation of our own myAdvance(iter, n) function demonstrating such function dispatching:

template <typename Iter, typename Distance>void advanceHelper(Iter& iter, Distance n, input_iterator_tag){ while (n > 0) { ++iter; --n; }}

template <typename Iter, typename Distance>void advanceHelper(Iter& iter, Distance n, bidirectional_iterator_tag){ while (n > 0) { ++iter; --n; } while (n < 0) { --iter; ++n; }}

template <typename Iter, typename Distance>void advanceHelper(Iter& iter, Distance n, random_access_iterator_tag){ iter += n;}

template <typename Iter, typename Distance>void myAdvance(Iter& iter, Distance n){ using category = typename iterator_traits<Iter>::iterator_category; advanceHelper(iter, n, category {});}This implementation of myAdvance() can be used on random-access iterators from vectors, on bidirectional iterators from lists, and so on:

template <typename Iter>void testAdvance(Iter iter){ print("*iter = {} | ", *iter); myAdvance(iter, 3); print("3 ahead = {} | ", *iter); myAdvance(iter, -2); println("2 back = {}", *iter);}

int main(){ vector vec { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 }; testAdvance(begin(vec)); list lst { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 }; testAdvance(begin(lst));}The output is as follows:

*iter = 1 | 3 ahead = 4 | 2 back = 2*iter = 1 | 3 ahead = 4 | 2 back = 2With concepts (see Chapter 12), the myAdvance() implementation can be simplified. Instead of using helper functions, you can just provide myAdvance() overloads with appropriate constraints:

template <input_iterator Iter, typename Distance>void myAdvance(Iter& iter, Distance n){ while (n > 0) { ++iter; --n; }}

template <bidirectional_iterator Iter, typename Distance>void myAdvance(Iter& iter, Distance n){ while (n > 0) { ++iter; --n; } while (n < 0) { --iter; ++n; }}

template <random_access_iterator Iter, typename Distance>void myAdvance(Iter& iter, Distance n){ iter += n;}STREAM ITERATORS

Section titled “STREAM ITERATORS”The Standard Library provides four stream iterators. These are iterator-like class templates that allow you to treat input and output streams as input and output iterators. Using these stream iterators, you can adapt input and output streams so that they can serve as sources and destinations, respectively, for various Standard Library algorithms. The following stream iterators are available:

ostream_iterator: Output iterator writing to abasic_ostreamistream_iterator: Input iterator reading from abasic_istreamostreambuf_iterator: Output iterator writing to abasic_streambufistreambuf_iterator: Input iterator reading from abasic_streambuf

Output Stream Iterator: ostream_iterator

Section titled “Output Stream Iterator: ostream_iterator”ostream_iterator is an output stream iterator. It is a class template that takes the element type as a template type parameter. The constructor takes an output stream and a delimiter string to write to the stream following each element. The ostream_iterator class writes elements using operator<<.

Let’s look at an example. Suppose you have the following myCopy() function template that copies a common range given as a begin and end iterator to a target range given as a begin iterator. The second template type parameter is constrained to be an output iterator that accepts values of type std::iter_reference:t<InputIter> which is the type of the values referred to by the given InputIter.

template <input_iterator InputIter, output_iterator<iter_reference:t<InputIter>> OutputIter>void myCopy(InputIter begin, InputIter end, OutputIter target){ for (auto iter { begin }; iter != end; ++iter, ++target) { *target = *iter; }}The first two parameters of myCopy() are the begin and end iterator of the range to copy, and the third parameter is an iterator to the destination range. You have to make sure the destination range is big enough to hold all the elements from the source range. Using the myCopy() function template to copy the elements of one vector to another one is straightforward.

vector myVector { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 };// Use myCopy() to copy myVector to vectorCopy.vector<int> vectorCopy(myVector.size());myCopy(cbegin(myVector), cend(myVector), begin(vectorCopy));Now, by using an ostream_iterator, the myCopy() function template can also be used to print elements of a container with just a single line of code. The following code snippet prints the contents of myVector and vectorCopy:

// Use the same myCopy() to print the contents of both vectors.myCopy(cbegin(myVector), cend(myVector), ostream_iterator<int> { cout, " " });println("");myCopy(cbegin(vectorCopy), cend(vectorCopy), ostream_iterator<int> { cout, " " });println("");The output is as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 101 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10Input Stream Iterator: istream_iterator

Section titled “Input Stream Iterator: istream_iterator”You can use the input stream iterator, istream_iterator, to read values from an input stream using the iterator abstraction. It is a class template that takes the element type as a template type parameter. Its constructor takes an input stream as a parameter. Elements are read using operator>>. You can use an istream_iterator as a source for algorithms and container member functions.

Suppose you have the following sum() function template that calculates the sum of all the elements in a given common range:

template <input_iterator InputIter>auto sum(InputIter begin, InputIter end){ auto sum { *begin }; for (auto iter { ++begin }; iter != end; ++iter) { sum += *iter; } return sum;}Now, an istream_iterator can be used to read integers from the console until the end of the stream is reached. On Windows, this happens when you press Ctrl+Z followed by Enter, while on Linux you press Enter followed by Ctrl+D. The sum() function is used to calculate the sum of all the integers. A default constructed istream_iterator represents the end iterator.

println("Enter numbers separated by whitespace.");println("Press Ctrl+Z followed by Enter to stop.");istream_iterator<int> numbersIter { cin };istream_iterator<int> endIter;int result { sum(numbersIter, endIter) };println("Sum: {}", result);Input Stream Iterator: istreambuf_iterator

Section titled “Input Stream Iterator: istreambuf_iterator”One use case of the istreambuf_iterator input stream iterator is to easily read the contents of an entire file with a single statement. A default constructed istreambuf_iterator represents the end iterator. Here is an example:

ifstream inputFile { "some_data.txt" };if (inputFile.fail()) { println(cerr, "Unable to open file for reading."); return 1;}string fileContents { istreambuf_iterator<char> { inputFile }, istreambuf_iterator<char> { }};println("{}", fileContents);ITERATOR ADAPTERS

Section titled “ITERATOR ADAPTERS”The Standard Library provides a number of iterator adapters, which are special iterators, all defined in <iterator>. They are split into two groups. The first group of adapters are created from a container and are usually used as output iterators:

- back_insert_iterator: Uses

push_back()to insert elements into a container - front_insert_iterator: Uses

push_front()to insert elements into a container - insert_iterator: Uses

insert()to insert elements into a container

Other adapters are created from another iterator, not a container, and are usually used as input iterators. Two common adapters are:

- reverse_iterator: Reverse the iteration order of another iterator.

- move_iterator: The dereferencing operator for a

move_iteratorautomatically converts the value to an rvalue reference, so it can be moved to a new destination.

It’s also possible to write your own iterator adapters, but this is not covered in this book. Consult one of the Standard Library references listed in Appendix B, “Annotated Bibliography,” for details.

Insert Iterators

Section titled “Insert Iterators”The myCopy() function template as implemented earlier in this chapter does not insert elements into a container; it simply replaces old elements in a range with new ones. To make such algorithms more useful, the Standard Library provides three insert iterator adapters that really insert elements into a container: insert_iterator, back_insert_iterator, and front_insert_iterator. They are all parametrized on a container type and take an actual container reference in their constructor. Because they supply the necessary iterator interfaces, these adapters can be used as the destination iterators for algorithms like myCopy(). However, instead of replacing elements in the container, they make calls on their container to actually insert new elements.

The basic insert_iterator calls insert(position,element) on the container, back_insert_iterator calls push_back(element), and front_insert_iterator calls push_front(element).

The following example uses a back_insert_iterator with myCopy() to populate vectorTwo with copies of all elements from vectorOne. Note that vectorTwo is not first resized to have enough elements, the insert iterator takes care of properly inserting new elements.

vector vectorOne { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 };vector<int> vectorTwo;

back_insert_iterator<vector<int>> inserter { vectorTwo };myCopy(cbegin(vectorOne), cend(vectorOne), inserter);

println("{:n}", vectorTwo);As you can see, when you use insert iterators, you don’t need to size the destination containers ahead of time.

You can also use the std::back_inserter() utility function to create a back_insert_iterator. In the previous example, you can remove the line that defines the inserter variable and rewrite the myCopy() call as follows. The result remains the same.

myCopy(cbegin(vectorOne), cend(vectorOne), back_inserter(vectorTwo));With class template argument deduction (CTAD), this can also be written as follows:

myCopy(cbegin(vectorOne), cend(vectorOne), back_insert_iterator { vectorTwo });The front_insert_iterator and insert_iterator work similarly, except that the insert_iterator also takes an initial iterator position in its constructor, which it passes to the first call to insert(position,element). Subsequent iterator position hints are generated based on the return value from each insert() call.

One benefit of using an insert_iterator is that it allows you to use associative containers as destinations of modifying algorithms. Chapter 20, “Mastering Standard Library Algorithms,” explains that the problem with associative containers is that you are not allowed to modify the keys over which you iterate. By using an insert_iterator, you insert elements instead of modifying existing ones. Associative containers have an insert() member function that takes an iterator position and can use the position as a “hint,” which they can ignore. When you use an insert_iterator on an associative container, you can pass the begin() or end() iterator of the container as the hint. The insert_iterator modifies the iterator hint that it passes to insert() after each call to insert(), such that the position is one past the just-inserted element.

Here is the previous example modified so that the destination container is a set instead of a vector:

vector vectorOne { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 };set<int> setOne;

insert_iterator<set<int>> inserter { setOne, begin(setOne) };myCopy(cbegin(vectorOne), cend(vectorOne), inserter);

println("{:n}", setOne);Similar to the back_insert_iterator example, you can use the std::inserter() utility function to create an insert_iterator:

myCopy(cbegin(vectorOne), cend(vectorOne), inserter(setOne, begin(setOne)));Or, use class template argument deduction:

myCopy(cbegin(vectorOne), cend(vectorOne), insert_iterator { setOne, begin(setOne) });Reverse Iterators

Section titled “Reverse Iterators”The Standard Library provides an std::reverse_iterator class template that iterates through a bidirectional or random-access iterator in a reverse direction. Every reversible container in the Standard Library, which happens to be every container that’s part of the standard except forward_list and the unordered associative containers, supplies a reverse_iterator type alias and member functions called rbegin() and rend(). These reverse_iterator type aliases are of type std::reverse_iterator<T> with T equal to the iterator type alias of the container. The member function rbegin() returns a reverse_iterator pointing to the last element of the container, and rend() returns a reverse_iterator pointing to the element before the first element of the container. Applying operator++ to a reverse_iterator calls operator-- on the underlying container iterator, and vice versa. For example, iterating over a collection from the beginning to the end can be done as follows:

for (auto iter { begin(collection) }; iter != end(collection); ++iter) {}Iterating over the elements in the collection from the end to the beginning can be done using a reverse_iterator by calling rbegin() and rend(). Note that you still call ++iter.

for (auto iter { rbegin(collection) }; iter != rend(collection); ++iter) {}An std::reverse_iterator is useful mostly with algorithms in the Standard Library or your own functions that have no equivalents that work in reverse order. The myFind() function introduced earlier in this chapter searches for the first element in a sequence. If you want to find the last element in the sequence, you can use a reverse_iterator. Note that when you call an algorithm such as myFind() with a reverse_iterator, it returns a reverse_iterator as well. You can always obtain the underlying iterator from a reverse_iterator by calling its base() member function. However, because of how reverse_iterator is implemented, the iterator returned from base() always refers to one element past the element referred to by the reverse_iterator on which it’s called. To get to the same element, you must subtract one.

Here is an example of myFind() with a reverse_iterator:

vector myVector { 11, 22, 33, 22, 11 };auto it1 { myFind(begin(myVector), end(myVector), 22) };auto it2 { myFind(rbegin(myVector), rend(myVector), 22) };if (it1 != end(myVector) && it2 != rend(myVector)) { println("Found at position {} going forward.", distance(begin(myVector), it1)); println("Found at position {} going backward.", distance(begin(myVector), --it2.base()));} else { println("Failed to find.");}The output of this program is as follows:

Found at position 1 going forward.Found at position 3 going backward.Move Iterators

Section titled “Move Iterators”Chapter 9, “Mastering Classes and Objects,” discusses move semantics, which can be used to prevent unnecessary copying in cases where you know that the source object will be destroyed after an assignment operation or copy construction, or explicitly when using std::move(). The Standard Library provides an iterator adapter called std::move_iterator. The dereferencing operator of a move_iterator automatically converts the value to an rvalue reference, which means that the value can be moved to a new destination without the overhead of copying. Before you can use move semantics, you need to make sure your objects are supporting it. The following MoveableClass supports move semantics. For more details, see Chapter 9.

class MoveableClass{ public: MoveableClass() { println("Default constructor"); } MoveableClass(const MoveableClass& src) { println("Copy constructor"); } MoveableClass(MoveableClass&& src) noexcept { println("Move constructor"); } MoveableClass& operator=(const MoveableClass& rhs) { println("Copy assignment operator"); return *this; } MoveableClass& operator=(MoveableClass&& rhs) noexcept { println("Move assignment operator"); return *this; }};The constructors and assignment operators are not doing anything useful here, except printing a message to make it easy to see which one is being called. Now that you have this class, you can define a vector and store a few MoveableClass instances in it as follows:

vector<MoveableClass> vecSource;MoveableClass mc;vecSource.push_back(mc);vecSource.push_back(mc);The output could be as follows. The numbers behind each line are not part of the output but are added to make it easier for the upcoming discussion to refer to specific lines.

Default constructor // [1]Copy constructor // [2]Copy constructor // [3]Move constructor // [4]The second line of the code creates a MoveableClass instance by using the default constructor, [1]. The first push_back() call triggers the copy constructor to copy mc into the vector, [2]. After this operation, the vector has space for one element, the first copy of mc. Note that this discussion is based on the growth strategy and the initial size of a vector as implemented by Microsoft Visual C++ 2022. The C++ standard does not specify the initial capacity of a vector or its growth strategy, so the output can be different with different compilers.

The second push_back() call triggers the vector to resize itself, to allocate space for the second element. This resizing causes the move constructor to be called to move every element from the old vector to the new resized vector, [4]. The copy constructor is triggered to copy mc a second time into the vector, [3]. The order of moving and copying is undefined, so [3] and [4] could be reversed.

You can create a new vector called vecOne that contains a copy of the elements from vecSource as follows:

vector<MoveableClass> vecOne { cbegin(vecSource), cend(vecSource) };Without using move_iterators, this code triggers the copy constructor two times, once for every element in vecSource:

Copy constructorCopy constructorBy using std::make_move_iterator() to create move_iterators, the move constructor of MoveableClass is called instead of the copy constructor:

vector<MoveableClass> vecTwo { make_move_iterator(begin(vecSource)), make_move_iterator(end(vecSource)) };This generates the following output:

Move constructorMove constructorYou can also use class template argument deduction (CTAD) with move_iterator:

vector<MoveableClass> vecTwo { move_iterator { begin(vecSource) }, move_iterator { end(vecSource) } };Remember that you should no longer use an object once it has been moved to another object.

RANGES

Section titled “RANGES”The iterator support of the C++ Standard Library allows algorithms to work independently of the actual containers, as they abstract away the mechanism to navigate through the elements of a container. As you’ve seen in all iterator examples up to now, most algorithms need an iterator pair consisting of a begin iterator that refers to the first element in the sequence, and an end iterator referring to one past the last element in the sequence. This makes it possible for algorithms to work on all kinds of containers, but it’s a bit cumbersome to always have to provide two iterators to specify a sequence of elements and to make sure you don’t provide mismatching iterators. Ranges provided by the ranges library are an abstraction layer on top of iterators, eliminating mismatching iterator errors, and adding extra functionality such as allowing range adapters to lazily filter and transform underlying sequences of elements. The ranges library, defined in <ranges>, consists of the following major components:

- Ranges: A range is a concept (see Chapter 12) defining the requirements for a type that allows iteration over its elements. Any data structure that supports

begin()andend()is a valid range. For example,std::array,vector,string_view,span, fixed-size C-style arrays, and so on, are all valid ranges. - Constrained algorithms: Chapters 16 and 20 discuss the available Standard Library algorithms accepting iterator pairs to perform their work. For most of these algorithms there are equivalent range-based and constrained variants that accept iterator pairs or ranges.

- Projection: A lot of the constrained algorithms accept a projection callback. This callback is called for each element in the range and can transform an element to some other value before it is passed to the algorithm.

- Views: A view can be used to transform or filter the elements of an underlying range. Views can be composed together to form pipelines of operations to be applied to a range.

- Factories: A range factory is used to construct a view that produces values on demand.

Iteration over the elements in a range can be done with iterators that can be retrieved with accessors such as ranges::begin(), end(), rbegin(), and so on. Ranges also support ranges::empty(), data(), cdata(), and size(). The latter returns the number of elements in a range but works only if the size can be retrieved in constant time. Otherwise, use std::distance() to calculate the number of elements between a begin and end iterator of a range. All these accessors are not member functions but stand-alone free functions, all requiring a range as argument.

Additionally, std::format(), print(), and println() have full support for formatting and printing ranges, as is demonstrated by numerous examples throughout this section.

Constrained Algorithms

Section titled “Constrained Algorithms”The std::sort() algorithm is an example of an algorithm that requires a sequence of elements specified as a begin and end iterator. Algorithms are introduced in Chapter 16 and discussed in detail in Chapter 20. The sort() algorithm is straightforward to use. For example, the following code sorts all the elements of a vector:

vector data { 33, 11, 22 };sort(begin(data), end(data));This code sorts all the elements in the data container, but you have to specify the sequence as a begin/end iterator pair. Wouldn’t it be nicer to more accurately describe in your code what you really want to do? That’s where the range-based and constrained algorithms, simply called constrained algorithms in this book, come in. These algorithms live in the std::ranges namespace and are defined in the same header file as the corresponding unconstrained variants. With those, you can simply write the following:

ranges::sort(data);This code clearly describes your intent, that is, sorting all elements of the data container. Since you are not specifying iterators anymore, these constrained algorithms eliminate the possibility of accidentally supplying mismatching begin and end iterators. The constrained algorithms have proper type constraints (see Chapter 12) for their template type parameters. This allows compilers to provide clearer error messages in case you supply a container to a constrained algorithm that does not provide the type of iterator the algorithm requires. For example, calling the ranges::sort() algorithm on an std::list will result in a compiler error stating more clearly that sort() requires a random-access range, which list isn’t. Similar to iterators, you have input-, output-, forward-, bidirectional-, random-access-, and contiguous ranges, with corresponding concepts such as ranges::contiguous_range, ranges::random_access_range, and so on.

Projection

Section titled “Projection”A lot of the constrained algorithms have a projection parameter, a callback used to transform each element before it is handed over to the algorithm. Let’s look at an example. Suppose you have a simple class representing a person:

class Person{ public: explicit Person(string first, string last) : m_firstName { move(first) }, m_lastName { move(last) } { } const string& getFirstName() const { return m_firstName; } const string& getLastName() const { return m_lastName; } private: string m_firstName; string m_lastName;};The following code stores a couple of Person objects in a vector:

vector persons { Person {"John", "White"}, Person {"Chris", "Blue"} };Since the Person class does not implement operator<, you cannot sort this vector using the normal std::sort() algorithm, as it compares elements using operator<. So, the following does not compile:

sort(begin(persons), end(persons)); // Error: does not compile.Switching to the constrained ranges::sort() algorithm doesn’t help much at first sight. The following still doesn’t compile as the algorithm still doesn’t know how to compare elements in the range:

ranges::sort(persons); // Error: does not compile.However, you can sort persons based on their first name, by specifying a projection function for the sort algorithm to project each person to their first name. The projection parameter is the third one, so we have to specify the second parameter as well, which is the comparator to use, by default std::ranges::less. In the following call, the {} specifies to use the default comparator, and the projection function is specified as a lambda expression, see upcoming note.

ranges::sort(persons, {}, [](const Person& person) { return person.getFirstName(); });Or even shorter:

ranges::sort(persons, {}, &Person::getFirstName);A view allows you to perform operations on an underlying range’s elements, such as filtering and transforming. Views can be chained/composed together to form a pipeline performing multiple operations on the elements of a range. Composing views is easy, you just combine different operations using the bitwise OR operator, operator|. For example, you can easily filter the elements of a range first and then transform the remaining elements. In contrast, if you want to do something similar, filtering followed by transforming, using the unconstrained algorithms, your code will be much less readable and possibly less performant, as you’ll have to create temporary containers to store intermediate results.

A view has the following important properties:

- Lazily evaluated: Just constructing a view doesn’t perform any operations yet. The operations of a view are applied only at the moment you iterate over the elements of the view and dereference such an iterator.

- Nonowning1: A view doesn’t own any elements. As the name suggests, it’s a view over a range’s elements that could be stored in some container, and it’s that container that’s the owner of the data. A view just allows you to view that data in different ways. As such, the number of elements in a view does not influence the cost of copying, moving, or destroying a view. This is similar to

std::string_viewdiscussed in Chapter 2, “Working with Strings and String Views,” andstd::spandiscussed in Chapter 18, “Standard Library Containers.” - Nonmutating: A view never modifies the data in the underlying range.

A view itself is also a range, but not every range is a view. A container is a range but not a view, as it owns its elements.

Views can be created using range adapters. A range adapter accepts an underlying sequence of elements, and optionally some arguments, and creates a new view. The following table lists the range adapters provided by the Standard Library. If none of the Standard Library adapters suits your needs, it’s possible to write your own range adapters that properly interoperate with existing adapters. However, writing a full-fledged production-quality range adapter is not trivial and would take us a bit too far for the scope of this book. See your favorite Standard Library reference for more details.

| RANGE ADAPTER | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

views::all | Creates a view that includes all elements of a range. |

filter_view views::filter | Filters the elements of an underlying sequence based on a given predicate. If the predicate returns true, the element is kept, otherwise it is skipped. |

transform_view views::transform | Applies a callback to each element of an underlying sequence to transform the element to some other value, possibly of a different type. |

take_view views::take | Creates a view of the first n elements of another view. |

take_while_view views::take_while | Creates a view of the initial elements of an underlying sequence until an element is reached for which a given predicate returns false. |

drop_view views::drop | Creates a view by dropping the first n elements of another view. |

drop_while_view views::drop_while | Creates a view by dropping all initial elements of an underlying sequence until an element is reached for which a given predicate returns false. |

join_view views::join | Flattens a view of ranges into a view. For example, flatten a vector<vector<int>> into a vector<int>. |

lazy_split_view views::lazy_split split_view views::split | Given a delimiter, splits a given view into subranges on the delimiter. The delimiter can be a single element or a view of elements. |

reverse_view views::reverse | Creates a view that iterates over the elements of another view in reverse order. The view must be a bidirectional view. |

elements_view views::elements | Requires a view of tuple-like elements, creates a view of the n**th elements of the tuple-like elements. |

keys_view views::keys | Requires a view of pair-like elements, creates a view of the first element of each pair. |

values_view views::values | Requires a view of pair-like elements, creates a view of the second element of each pair. |

common_view views::common | Depending on the type of range, begin() and end() might return different types, such as a begin iterator and an end sentinel. This means that you cannot, for example, pass such an iterator pair to functions that expect them to be of the same type. common_view can be used to convert such a range to a common range which is a range for which begin() and end() return the same type. You will use this range adapter in one of the exercises. |

| RANGE ADAPTER | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

as_const_view views::as_const | Creates a view through which the elements of an underlying sequence cannot be modified. |

as_rvalue_view views::as_rvalue | Creates a view of rvalues of all elements of an underlying sequence. |

enumerate_view views::enumerate | Creates a view where each element represents the position and value of all elements of an underlying sequence. |

zip_view views::zip | Creates a view consisting of tuples of reference to corresponding elements of all given views. |

zip_transform_view views::zip_transform | Creates a view whose i**th element is the result of applying a given callable to the i**th elements of all given views. |

adjacent_view views::adjacent | For a given n, creates a view whose i**th element is a tuple of references to the i**th through (i + n − 1)th elements of a given view. |

adjacent_transform_view views::adjacent_transform | For a given n, creates a view whose i**th element is the result of applying a given callable to the i**th through (i + n − 1)th elements of a given view. |

views::pairwise views::pairwise_transform | Helper types representing views::adjacent<2> and views::adjacent_transform<2> respectively. |

join_with_view views::join_with | Given a delimiter, flattens the elements of a given view, inserting every element of the delimiter in between elements of the view. The delimiter can be a single element or a view of elements. |

stride_view views::stride | For a given n, creates a view of an underlying sequence, advancing over n elements at a time, instead of one by one. |

slide_view views::slide | For a given n, creates a view whose i**th element is a view over the i**th through (i + n − 1)th elements of the original view. Similar to views::adjacent, but the window size, n, is a runtime parameter for slide, while it’s a template argument for adjacent. |

chunk_view views::chunk | For a given n, creates a range of views that are n-sized non-overlapping successive chunks of the elements of the original view, in order. |

chunk_by_view views::chunk_by | Splits a given view into subranges between each pair of adjacent elements for which a given predicate returns false. |

cartesian_product_view views::cartesian_product | Given a number of ranges, n, creates a view of tuples calculated by the n-ary cartesian product of the provided ranges. |

The range adapters in the first column of both tables show both the class name in the std::ranges namespace and a corresponding range adapter object from the std::ranges::views namespace. The Standard Library provides a namespace alias called std::views equal to std::ranges::views.

Each range adapter can be constructed by calling its constructor and passing any required arguments. The first argument is always the range on which to operate, followed by zero or more additional arguments, as follows:

std::ranges::operation_view { range, arguments… }Usually, you will not create these range adapters using their constructors, but instead use the range adapter objects from the std::ranges::views namespace in combination with the bitwise OR operator, |, as follows:

range | std::ranges::views::operation(arguments…)Let’s see some of these range adapters in action. The following example first defines an abbreviated function template called printRange() to print a message followed by all the elements in a given range. Next, the main() function starts by creating a vector of integers, 1…10, and subsequently applies several range adapters on it, each time calling printRange() on the result so you can follow what’s happening. Afterward, it demonstrates several of the new C++23 range adapters. The example uses the myCopy() function introduced earlier in this chapter.

void printRange(string_view msg, auto&& range) { println("{}{:n}", msg, range); }

int main(){ vector values { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 }; printRange("Original sequence: ", values);

// Filter out all odd values, leaving only the even values. auto result1 { values | views::filter([](const auto& value) { return value % 2 == 0; }) }; printRange("Only even values: ", result1);

// Transform all values to their double value. auto result2 { result1 | views::transform([](const auto& value) { return value * 2.0; }) }; printRange("Values doubled: ", result2);

// Drop the first 2 elements. auto result3 { result2 | views::drop(2) }; printRange("First two dropped: ", result3);

// Reverse the view. auto result4 { result3 | views::reverse }; printRange("Sequence reversed: ", result4);

// C++23: views::zip vector v1 { 1, 2 }; vector v2 { 'a', 'b', 'c' }; auto result5 { views::zip(v1, v2) }; printRange("views::zip: ", result5);

// C++23: views::adjacent vector v3 { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }; auto result6 { v3 | views::adjacent<2> }; printRange("views::adjacent: ", result6);

// C++23: views::chunk auto result7 { v3 | views::chunk(2) }; printRange("views::chunk: ", result7);

// C++23: views::stride auto result8 { v3 | views::stride(2) }; printRange("views::stride: ", result8);

// C++23: views::enumerate + views::split string lorem { "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet" }; for (auto [index, word] : lorem | views::split(' ') | views::enumerate) { print("{}:'{}' ", index, string_view { word }); } println("");

// C++23: views::as_rvalue vector<string> words { "Lorem", "ipsum", "dolor", "sit", "amet" }; vector<string> movedWords; auto rvalueView { words | views::as_rvalue }; myCopy(begin(rvalueView), end(rvalueView), back_inserter(movedWords)); printRange("movedWords: ", movedWords);

// C++23: Cartesian product of vector v with itself. vector v { 0, 1, 2 }; for (auto&&[a, b] : views::cartesian_product(v, v)) {print("({},{}) ", a, b);}}The output of this program is as follows:

Original sequence: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10Only even values: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10Values doubled: 4, 8, 12, 16, 20First two dropped: 12, 16, 20Sequence reversed: 20, 16, 12views::zip: (1, 'a'), (2, 'b')views::adjacent: (1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 4), (4, 5)views::chunk: (1, 2), (3, 4), (5)views::stride: 1, 3, 50:'Lorem' 1:'ipsum' 2:'dolor' 3:'sit' 4:'amet'movedWords: Lorem, ipsum, dolor, sit, amet(0,0) (0,1) (0,2) (1,0) (1,1) (1,2) (2,0) (2,1) (2,2)It’s worth repeating that views are lazily evaluated. In this example, the construction of the result1 view does not do any actual filtering yet. The filtering happens at the time when the printRange() function iterates over the elements of result1.

The code snippet uses the range adapter objects from std::ranges::views. You can also construct range adapters using their constructors. For example, the result1 view can be constructed as follows:

auto result1 { ranges::filter_view { values, [](const auto& value) { return value % 2 == 0; } } };This example is creating several intermediate views, result1, result2, result3, and result4, to be able to output their elements to make it easier to follow what’s happening in each step. If you don’t need these intermediate views, you can chain them all together in a single pipeline as follows:

vector values { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 };printRange("Original sequence: ", values);

auto result { values | views::filter([](const auto& value) { return value % 2 == 0; }) | views::transform([](const auto& value) { return value * 2.0; }) | views::drop(2) | views::reverse };printRange("Final sequence: ", result);The output is as follows. The last line shows that the final sequence is the same as the earlier result4 view.

Original sequence: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10Final sequence: 20, 16, 12Modifying Elements Through a View

Section titled “Modifying Elements Through a View”Some ranges are read-only. For example, the result of views::transform is a read-only view, because it creates a view with transformed elements but without transforming the actual values in the underlying range. If a range is not read-only, then you can modify the elements of that range through a view. Let’s look an example.

The following example constructs a vector of ten elements. It then creates a view over the even values, drops the first two even values, and finally reverses the elements. The range-based for loop then multiplies the elements in the resulting view with 10. The last line outputs the elements in the original values vector to confirm that some elements have been changed through the view.

vector values { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 };printRange("Original sequence: ", values);

// Filter out all odd values, leaving only the even values.auto result1 { values | views::filter([](const auto& value) { return value % 2 == 0; }) };printRange("Only even values: ", result1);

// Drop the first 2 elements.auto result2 { result1 | views::drop(2) };printRange("First two dropped: ", result2);

// Reverse the view.auto result3 { result2 | views::reverse };printRange("Sequence reversed: ", result3);

// Modify the elements using a range-based for loop.for (auto& value : result3) { value *= 10; }printRange("After modifying elements through a view, vector contains:\n", values);The output of this program is as follows:

Original sequence: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10Only even values: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10First two dropped: 6, 8, 10Sequence reversed: 10, 8, 6After modifying elements through a view, vector contains: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 60, 7, 80, 9, 100Mapping Elements

Section titled “Mapping Elements”Transforming elements of a range doesn’t need to result in a range with elements of the same type. Instead, you can map elements to another type. The following example starts with a range of integers, filters out all odd elements, keeps only the first three even values, and transforms those to strings using std::format():

vector values { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 };printRange("Original sequence: ", values);

auto result { values | views::filter([](const auto& value) { return value % 2 == 0; }) | views::take(3) | views::transform([](const auto& v) { return format("{}", v); }) };printRange("Result: ", result);The output is as follows:

Original sequence: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10Result: "2", "4", "6"Range Factories

Section titled “Range Factories”The ranges library provides the following range factories to construct views that produce elements lazily on demand:

| RANGE FACTORY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

empty_view | Creates an empty view. |

single_view | Creates a view with a single given element. |

iota_view | Creates an infinite or a bounded view containing elements starting with an initial value, and where each subsequent element has a value equal to the value of the previous element incremented by one. |

repeat_view | Creates a view that repeats a given value. The resulting view can be unbounded (infinite) or bounded by a given number of values. |

basic_istream_view istream_view | Creates a view containing elements retrieved by calling the extraction operator, operator>>, on an underlying input stream. |

Just as with the range adapters from the previous section, the names in the range factories table are class names living in the std::ranges namespace, which you can directly create using their constructor. Alternatively, you can use the factory functions available in the std::ranges:views namespace. For example, the following two statements are equivalent and create an infinite view with elements 10, 11, 12, …:

std::ranges::iota_view { 10 }std::ranges::views::iota(10)Let’s look at a range factory in practice. The following example is loosely based on an earlier example, but instead of constructing a vector with 10 elements in it, this code uses the iota range factory to create a lazy infinite sequence of numbers starting at 10. It then removes all odd values, doubles the remaining elements, and finally only keeps the first ten elements that are subsequently output to the console using printRange().

// Create an infinite sequence of the numbers 10, 11, 12, …auto values { views::iota(10) };// Filter out all odd values, leaving only the even values.auto result1 { values | views::filter([](const auto& value) { return value % 2 == 0; }) };// Transform all values to their double value.auto result2 { result1 | views::transform([](const auto& value) { return value * 2.0; }) };// Take only the first ten elements.auto result3 { result2 | views::take(10) };printRange("Result: ", result3);The output is as follows:

Result: 20, 24, 28, 32, 36, 40, 44, 48, 52, 56The values range represents an infinite range, which is subsequently filtered and transformed. Working with infinite ranges is possible because all these operations are lazily evaluated only at the time when printRange() iterates over the elements of the view. This also means that in this example you cannot call printRange() to output the contents of values, result1, or result2 because that would trigger an infinite loop in printRange() as those are infinite ranges.

Of course, you can get rid of those intermediate views and simply construct one big pipeline. The following produces the same output as before:

auto result { views::iota(10) | views::filter([](const auto& value) { return value % 2 == 0; }) | views::transform([](const auto& value) { return value * 2.0; }) | views::take(10) };printRange("Result: ", result);Another range factory example demonstrates how to use a repeat_view:

printRange("Repeating view: ", views::repeat(42, 5));This outputs the following:

Repeating view: 42, 42, 42, 42, 42Input Streams as Views

Section titled “Input Streams as Views”The basic_istream_view/istream_view range factory can be used to construct a view over the elements read from an input stream, such as the standard input. Elements are read using operator>>.

For example, the following code snippet keeps reading integers from standard input. For each read number that is less than 5, the number is doubled and printed on standard output. Once you enter a number 5 or higher, the loop stops.

println("Type integers, an integer>= 5 stops the program.");for (auto value : ranges::istream_view<int> { cin } | views::take_while([](const auto& v) { return v < 5; }) | views::transform([](const auto& v) { return v * 2; })) { println("> {}", value);}println("Terminating…");The following is a possible output sequence:

Type integers, an integer>= 5 stops the program.1 2> 2> 43> 64> 85Terminating…

Section titled “ Converting a Range into a Container”Before C++23, it was not easy to convert a range into a container. C++23 introduces std::ranges::to() to make such conversions straightforward. This can also be used to convert the elements of a view into a container, as a view is a range. Even more, since a container is a range as well, you can use ranges::to() to convert one container into a different container, even with different element types.

The following code snippet demonstrates several uses of ranges::to(). The example also demonstrates special constructors for set and string, which accept the std::from_range tag as the first parameter and convert a given range into a set or string. All Standard Library containers now include such constructors.

// Convert a vector to a set with the same element type.vector vec { 33, 11, 22 };auto s1 { ranges::to<set>(vec) };println("{:n}", s1);

// Convert a vector of integers to a set of doubles, using the pipe operator.auto s2 { vec | ranges::to<set<double>>() };println("{:n}", s2);

// Convert a vector of integers to a set of doubles, using from_range constructor.set<double> s3 { from_range, vec };println("{:n}", s3);

// Lazily generate the integers from 10 to 14, divide these by 2,// and store the result in a vector of doubles.auto vec2 { views::iota(10, 15) | views::transform([](const auto& v) { return v / 2.0; }) | ranges::to<vector<double>>() };println("{:n}", vec2);

// Use views::split() and views::transform() to create a view// containing individual words of a string, and then convert// the resulting view to a vector of strings containing all the words.string lorem { "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet" };auto words { lorem | views::split(' ') | views::transform([](const auto& v) { return string { from_range, v }; }) | ranges::to<vector>() };println("{:n:?}", words);The output is as follows:

11, 22, 3311, 22, 3311, 22, 335, 5.5, 6, 6.5, 7"Lorem", "ipsum", "dolor", "sit", "amet"C++23 also introduces a number of new member functions for Standard Library containers, providing for interoperability between containers and ranges. These member functions are of the form xyz_range(…), where xyz can be insert, append, prepend, assign, replace, push, push_front, or push_back. Chapter 18 discusses all Standard Library containers in detail, but consult a Standard Library reference to learn exactly which member functions are supported by which container. Here is an example demonstrating the append_range() and insert_range() member functions of vector:

vector<int> vec3;vec3.append_range(views::iota(10, 15));println("{:n}", vec3);vec3.insert_range(begin(vec3), views::iota(10, 15) | views::reverse);println("{:n}", vec3);The output is:

10, 11, 12, 13, 1414, 13, 12, 11, 10, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14SUMMARY

Section titled “SUMMARY”This chapter explained the ideas behind iterators, which are an abstraction that allows you to navigate the elements of a container without the need to know the structure of the container. You have seen that output stream iterators can use standard output as a destination for iterator-based algorithms, and similarly that input stream iterators can use standard input as the source of data for algorithms. The chapter also discussed the insert-, reverse-, and move iterator adapters that can be used to adapt other iterators.

The last part of this chapter discussed the ranges library, part of the C++ Standard Library. It allows you to write more functional-style code, by specifying what you want to accomplish instead of how. You can construct pipelines consisting of a combination of operations applied to the elements of a range. Such pipelines are executed lazily; that is, they don’t do anything until you iterate over the resulting view.

EXERCISES

Section titled “EXERCISES”By solving the following exercises, you can practice the material discussed in this chapter. Solutions to all exercises are available with the code download on the book’s website at www.wiley.com/go/proc++6e. However, if you are stuck on an exercise, first reread parts of this chapter to try to find an answer yourself before looking at the solution from the website.

-

Exercise 17-1: Write a program that lazily constructs the sequence of elements 10-100, squares each number, removes all numbers dividable by five, and transforms the remaining values to strings using

std::to_string(). -

Exercise 17-2: Write a program that creates a

vectorofpairs, where eachpaircontains an instance of thePersonclass introduced earlier in this chapter, and their age. Next, use the ranges library to construct a single pipeline that extracts all ages from all persons from thevector, and removes all ages below 12 and above 65. Finally, calculate the average of the remaining ages using thesum()algorithm from earlier in this chapter. As you’ll pass a range to thesum()algorithm, you’ll have to work with a common range. -

Exercise 17-3: Building further on the solution for Exercise 17-2, add an implementation for

operator<<for thePersonclass.Next, create a pipeline to extract the

Personof eachpairfrom thevectorofpairs, and only keep the first fourPersons. Use themyCopy()algorithm introduced earlier in this chapter to print the names of those four persons to the standard output; one name per line.Finally, create a similar pipeline but one that additionally projects all filtered

Persons to their last name. This time, use a singleprintln()statement to print the last names to the standard output. -

Exercise 17-4: Write a program that uses a range-based

forloop andranges::istream_view()to read integers from the standard input until a -1 is entered. Store the read integers in avector, and afterward, print the content of thevectorto the console to verify it contains the correct values. -

Bonus exercise: Can you find a couple of ways to change the solution for Exercise 17-4 to not use any explicit loops? Hint: one option could be to use the

std::ranges::copy()algorithm to copy a range from a source to a target. It can be called with a range as first argument and an output iterator as the second argument.

Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

C++23 slightly modifies the definition of a view. It allows for a view to own its elements, but only if it guarantees that it’s either non-copyable, or copyable in constant time, O(1). Most views will be nonowning, so owning views are not further discussed in this text. ↩