Designing for Reuse

Reusing libraries and other code in your programs as discussed in Chapter 4, “Designing Professional C++ Programs,” is an important design strategy. However, it is only half of the reuse strategy. The other half is designing and writing your own code that you can reuse in your programs. As you’ve probably discovered, there is a significant difference between well-designed and poorly designed libraries. Well-designed libraries are a pleasure to use, while poorly designed libraries can prod you to give up in disgust and write the code yourself. Whether you’re writing a library explicitly designed for use by other programmers or merely deciding on a class hierarchy, you should design your code with reuse in mind. You never know when you’ll need a similar piece of functionality in a subsequent project.

Chapter 4 introduces the design theme of reuse and explains how to apply this theme by incorporating libraries and other code into your designs, but it doesn’t explain how to design reusable code. That is the topic of this chapter. It builds on the object-oriented design principles described in Chapter 5, “Designing with Classes.”

THE REUSE PHILOSOPHY

Section titled “THE REUSE PHILOSOPHY”You should design code that both you and other programmers can reuse. This rule applies not only to libraries and frameworks that you specifically intend for other programmers to use but also to any class, subsystem, or component that you design for a program. You should always keep in mind the following mottos:

- “Write once, use often.”

- “Try to avoid code duplication.”

- “DRY—Don’t Repeat Yourself.”

There are several reasons for this:

- Code is rarely used in only one program. You can be sure that your code will be used again somehow, so design it correctly to begin with.

- Designing for reuse saves time and money. If you design your code in a way that precludes future use, you ensure that you or your partners will spend time reinventing the wheel later when you encounter a need for a similar piece of functionality.

- Other programmers in your group must be able to use the code that you write. You are probably not working alone on a project. Your co-workers will appreciate your efforts to offer them well-designed, functionality-packed libraries and pieces of code to use. Designing for reuse can also be called cooperative coding.

- Lack of reuse leads to code duplication; code duplication leads to a maintenance nightmare. If a bug is found in duplicated code, it has to be fixed in all places where it got duplicated. Whenever you find yourself copy-pasting a piece of code, you have to at least consider moving it out to a helper function or class.

- You will be the primary beneficiary of your own work. Experienced programmers never throw away code. Over time, they build a personal library of evolving tools. You never know when you will need a similar piece of functionality in the future.

When you design or write code as an employee of a company, the company, not you, generally owns the intellectual property rights. It is often illegal to retain copies of your designs or code when you terminate your employment with the company. The same is also true when you are self-employed and working for clients.

HOW TO DESIGN REUSABLE CODE

Section titled “HOW TO DESIGN REUSABLE CODE”Reusable code fulfills two main goals:

- First, it is general enough to use for slightly different purposes or in different application domains. Program components with details of a specific application are difficult to reuse in other programs.

- Second, reusable code is also easy to use. It doesn’t require significant time to understand its interface or functionality. Programmers must be able to incorporate it readily into their applications.

The means of delivering your library to clients is also important. You can deliver it in source form, and clients just incorporate your source into their project. Another option is to deliver binaries in the form of static libraries, which they link into their application, or in the form of Dynamic Link Libraries (.dll) for Windows clients, or shared objects (.so) for Linux clients. Each of these delivery mechanisms can impose additional constraints on how you design your reusable code.

The most important strategy for designing reusable code is abstraction.

Use Abstraction

Section titled “Use Abstraction”The key to abstraction is effectively separating the interface from the implementation. The implementation is the code you’re writing to accomplish the task you set out to accomplish. The interface is the way that other people use your code. In C, the header file that describes the functions in a library you’ve written is an interface. In object-oriented programming, the collection of publicly accessible class member functions and class properties is the interface of the class. However, a good interface should contain only public member functions. Properties of a class should never be made public but can be exposed through public member functions, also called getters and setters.

Chapter 4 introduces the principle of abstraction and presents a real-world analogy of a television, which you can use through its interfaces without understanding how it works inside. Similarly, when you design code, you should clearly separate the interface from the implementation. This separation makes the code easier to use, primarily because clients do not need to understand the internal implementation details to use the functionality.

Using abstraction benefits both you and the clients who use your code. Clients benefit because they don’t need to worry about the implementation details; they can take advantage of the functionality you offer without understanding how the code really works. You benefit because you can modify the underlying code without changing the interface to the code. Thus, you can provide upgrades and fixes without requiring clients to change their use. With dynamically linked libraries, clients might not even need to rebuild their executables. Finally, you both benefit because you, as the library writer, can specify in the interface exactly what interactions you expect and what functionality you support. Consult Chapter 3, “Coding with Style,” for a discussion on how to write documentation. A clear separation of interfaces and implementations will prevent clients from using the library in ways that you didn’t intend, which can otherwise cause unexpected behaviors and bugs.

When designing your interface, do not expose implementation details to your clients.

Sometimes libraries require client code to keep information returned from one interface to pass it to another. This information is sometimes called a handle and is often used to keep track of specific instances that require state to be remembered between calls. A real-world example of this is OpenGL, a 2D/3D rendering library. Many functions of OpenGL return and work with handles, which are represented by the type GLuint. For example, if you use the OpenGL function glGenBuffers() to create a buffer, it returns you the buffer as a GLuint handle. Whenever you want to call another function to do something with that buffer, you must pass the GLuint handle to that function.

If your library design requires a handle, don’t expose its internals. Make that handle into an opaque class, in which the programmer can’t access the internal data members, neither directly nor through public getters or setters. Don’t require the client code to tweak variables inside this handle. An example of a bad design would be a library that requires you to set a specific member of a structure in a supposedly opaque handle in order to turn on error logging.

Abstraction is so important that it should guide your entire design. As part of every decision you make, ask yourself whether your choice fulfills the principle of abstraction. Put yourself in your clients’ shoes and determine whether you’re requiring knowledge of the internal implementation in the interface. You should rarely, if ever, make exceptions to this rule.

While designing reusable code using abstraction, you should focus on the following:

- First, you must structure the code appropriately. What class hierarchies will you use? Should you use templates? How should you divide the code into subsystems?

- Second, you must design the interfaces, which are the “entries” into your library to access the functionality you provide.

Both topics are discussed in the upcoming sections.

Structure Your Code for Optimal Reuse

Section titled “Structure Your Code for Optimal Reuse”You must consider reuse from the beginning of your design on all levels, that is, from a single function, over a class, to entire libraries and frameworks. In the text that follows, all these different levels are called components. The following strategies will help you organize your code properly. Note that all of these strategies focus on making your code general purpose. The second aspect of designing reusable code, providing ease of use, is more relevant to your interface design and is discussed later in this chapter.

Avoid Combining Unrelated or Logically Separate Concepts

Section titled “Avoid Combining Unrelated or Logically Separate Concepts”When you design a component, you should keep it focused on a single task or group of tasks, that is, you should strive for high cohesion. This is also known as the single responsibility principle (SRP). Don’t combine unrelated concepts such as a random number generator and an XML parser.

Even when you are not designing code specifically for reuse, keep this strategy in mind. Entire programs are rarely reused on their own. Instead, pieces or subsystems of the programs are incorporated directly into other applications or are adapted for slightly different uses. Thus, you should design your programs so that you divide logically separate functionality into distinct components that can be reused in different programs. Each such component should have well-defined responsibilities.

This program strategy models the real-world design principle of discrete, interchangeable parts. For example, you could write a Car class and put all properties and behaviors of the engine into it. However, engines are separable components that are not tied to other aspects of the car. The engine could be removed from one car and put into another car. A proper design would include an Engine class that contains all engine-specific functionality. A Car instance then just contains an instance of Engine.

Divide Your Programs into Logical Subsystems

Section titled “Divide Your Programs into Logical Subsystems”You should design your subsystems as discrete components that can be reused independently, that is, strive for low coupling. For example, if you are designing a networked game, keep the networking and graphical user interface aspects in separate subsystems. That way, you can reuse either component without dragging in the other one. For example, you might want to write a non-networked game, in which case you could reuse the graphical interface subsystem but wouldn’t need the networking aspect. Similarly, you could design a peer-to-peer file-sharing program, in which case you could reuse the networking subsystem but not the graphical user interface functionality.

Make sure to follow the principle of abstraction for each subsystem. Think of each subsystem as a miniature library for which you must provide a coherent and easy-to-use interface. Even if you’re the only programmer who ever uses these miniature libraries, you will benefit from well-designed interfaces and implementations that separate logically distinct functionality.

Use Class Hierarchies to Separate Logical Concepts

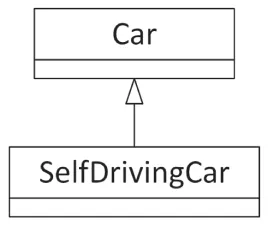

Section titled “Use Class Hierarchies to Separate Logical Concepts”In addition to dividing your program into logical subsystems, you should avoid combining unrelated concepts at the class level. For example, suppose you want to write a class for a self-driving car. You decide to start with a basic class for a car and incorporate all the self-driving logic directly into it. However, what if you just want a non-self-driving car in your program? In that case, all the logic related to self-driving is useless and might require your program to link with libraries that it could otherwise avoid, such as vision libraries, LIDAR libraries, and so on. One possible solution is to create a class hierarchy (introduced in Chapter 5) in which a self-driving car is a derived class of a generic car. That way, you can use the car base class in programs that do not need self-driving capabilities without incurring the cost of such algorithms. Figure 6.1 shows this hierarchy.

[^FIGURE 6.1]

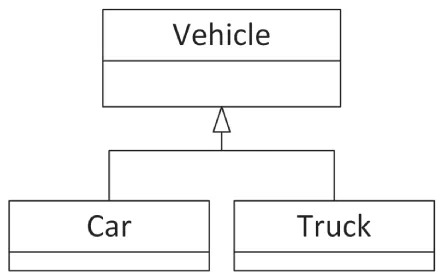

This strategy works well when there are two logical concepts, such as self-driving and cars. It becomes more complicated when there are three or more concepts. For example, suppose you want to provide both a truck and a car, each of which could be self-driving or not. Logically, both the truck and the car are a special case of a vehicle, and so they could be derived classes of a vehicle class, as shown in Figure 6.2.

[^FIGURE 6.2]

Similarly, self-driving classes could be derived classes of non-self-driving classes. You can’t provide these separations with a linear hierarchy. One possibility is to make the self-driving aspect a mixin class instead. The previous chapter shows one way to implement mixins in C++ by using multiple inheritance. For example, a PictureButton could inherit from both an Image class and a Clickable mixin class. However, for the self-driving design, it’s better to use a different kind of mixin implementation, one using class templates.

This example jumps ahead a bit on class template syntax, which is discussed in detail in Chapter 12, “Writing Generic Code with Templates,” but those details are not important to follow this discussion. It also jumps ahead a bit on the syntax of inheritance. Chapter 10, “Discovering Inheritance Techniques,” discusses inheritance in detail; however, those details are not important to understand this example. For now, you need to know only that the following syntax specifies that the Derived class inherits/derives from the Base class:

class Derived : public Base {};The SelfDrivable mixin class template can then be defined as follows:

template <typename T>class SelfDrivable : public T{};This SelfDrivable mixin class provides all the necessary algorithms for implementing the self-driving functionality. Once you have this SelfDrivable mixin class template, you can instantiate one for a car and one for a truck as follows:

SelfDrivable<Car> selfDrivingCar;SelfDrivable<Truck> selfDrivingTruck;The result of these two lines is that the compiler uses the SelfDrivable mixin class template to create one instantiation where all T’s of the class template are replaced by Car and hence is derived from Car, and another where the T’s are replaced by Truck and thus derives from Truck. Chapter 32, “Incorporating Design Techniques and Frameworks,” goes into more detail on mixin classes.

This solution requires you to write four different classes (Vehicle, Car, Truck, and SelfDrivable), but the clear separation of functionality is worth the effort.

Similarly, you should avoid combining unrelated concepts, that is, strive for high cohesion, at any level of your design, not only at the class level. For example, at the level of member functions, a single member function should not perform logically unrelated things, mix mutation (set) and inspection (get), and so on.

Use Aggregation to Separate Logical Concepts

Section titled “Use Aggregation to Separate Logical Concepts”Aggregation, discussed in Chapter 5, models the has-a relationship: objects contain other objects to perform some aspects of their functionality. As Chapter 5 explains, if you have a choice, prefer using has-a relationships over is-a relationships.

For example, suppose you want to write a FamilyTree class to store the members of a family. Obviously, a tree data structure would be ideal for storing this information. Instead of integrating the tree structure code directly in the FamilyTree class, you should write a separate Tree class. The FamilyTree class can then contain and use a Tree instance. To use the object-oriented terminology, FamilyTree has-a Tree. With this technique, the tree data structure could be reused more easily in another program.

Eliminate User Interface Dependencies

Section titled “Eliminate User Interface Dependencies”If your library is a data manipulation library, you want to separate data manipulation from the user interface. This means that for those kinds of libraries you should never assume in which type of user interface the library will be used. The library should not use any of the standard console output and input functionality, such as std::println() or cin, because if the library is used in the context of a graphical user interface, doing so may make no sense. For example, a Windows GUI-based application usually will not have any form of console I/O. If you think your library will only be used in GUI-based applications, you should still never pop up any kind of message box or other kind of notification to the end user, because that is the responsibility of the client code. It’s the client code that decides how messages are displayed to the user. These kinds of dependencies not only result in poor reusability, but they also prevent client code from properly responding to an error, for example, to handle it silently.

The Model-View-Controller (MVC) paradigm, introduced in Chapter 4, is a well-known design pattern to separate storing data from visualizing that data. With this paradigm, the model can be in the library, while the client code can provide the view and the controller.

Use Templates for Generic Data Structures and Algorithms

Section titled “Use Templates for Generic Data Structures and Algorithms”C++ has a concept called templates that allows you to create structures that are generic with respect to a type or class. For example, you might have written code for an array of integers. If you subsequently would like an array of doubles, you need to rewrite and replicate all the code to work with doubles. The notion of a template is that the type becomes a parameter to the specification, and you can create a single body of code that can work on any type. Templates allow you to write both data structures and algorithms that work on any types.

The simplest example of this is the in Chapter 1, “A Crash Course in C++ and the Standard Library,” introduced std::vector class, which is part of the C++ Standard Library. To create a vector of integers, you write std::vector<int>; to create a vector of doubles, you write std::vector<double>. Template programming is, in general, extremely powerful but can be very complex. Luckily, it is possible to create rather simple usages of templates that parameterize according to a type. Chapters 12 and 26, “Advanced Templates,” explain the techniques to write your own templates, while this section discusses some of their important design aspects.

Whenever possible, you should use a generic design for data structures and algorithms instead of encoding specifics of a particular program. Don’t write a balanced binary tree structure that stores only book objects. Make it generic, so that it can store objects of any type. That way, you could use it in a bookstore, a music store, an operating system, or anywhere that you need a balanced binary tree. This strategy underlies the Standard Library, which provides generic data structures and algorithms that work on any types.

However, at the same time, keep in mind that implementing a generic data structure takes more time compared to a non-generic implementation. You will need to think more about requirements, and you will need to test your generic implementation more extensively with many different types. If your data structure is very specific for a specific use case, this extra effort might not pay off, and you might be better off starting with a simple non-generic implementation.

Why Templates Are Better Than Other Generic Programming Techniques

Section titled “Why Templates Are Better Than Other Generic Programming Techniques”Templates are not the only mechanism for writing generic data structures. Another, albeit older and no longer recommended approach to write generic structures in C and C++ is to store void* pointers instead of pointers of a specific type. Clients can use this structure to store anything they want by casting it to a void*. However, the main problem with this approach is that it is not type safe: the containers are unable to check or enforce the types of the stored elements. You can cast any type to a void* to store in the structure, and when you remove the pointers from the data structure, you must cast them back to what you think they are. Because there are no checks involved, the results can be disastrous. Imagine a scenario where one programmer stores pointers to int in a data structure by first casting them to void*, but another programmer thinks they are pointers to Process objects. The second programmer will blithely cast the void* pointers to Process* pointers and try to use them as Process* objects. Needless to say, the program will not work as expected.

Instead of directly using void* pointers in your generic non-template-based data structures, you could use the std::any class, available since C++17. The any class is discussed in Chapter 24, “Additional Vocabulary Types,” but for this discussion it’s enough to know that you can store any type of object in an instance of the any class. The underlying implementation of std::any does use a void* pointer in certain cases, but it also keeps track of the type stored, so everything remains type safe.

Yet another approach is to write the data structure for a specific class. Through polymorphism, any derived class of that class can be stored in the structure. Java takes this approach to an extreme: it specifies that every class derives directly or indirectly from the Object class. The containers in earlier versions of Java store Objects, so they can store objects of any type. However, this approach is also not type safe. When you remove an object from the container, you must remember what it really is and down-cast it to the appropriate type. Down casting means casting it to a more specific class in a class hierarchy, that is, casting it downward in the hierarchy.

Templates, on the other hand, are type safe when used correctly. Each instantiation of a template stores only one type. Your program will not compile if you try to store different types in the same template instantiation. Additionally, templates allow the compiler to generate highly optimized code for each template instantiation. Compared to void* and std::any based data structures, templates can also avoid allocations on the free store, and hence have better performance. Newer versions of Java do support the concept of generics that are type safe just like C++ templates.

Problems with Templates

Section titled “Problems with Templates”Templates are not perfect. First of all, their syntax might be confusing, especially for someone who has not used them before. Second, templates require homogeneous data structures, in which you can store only objects of the same type in a single structure. That is, if you write a class template for a balanced binary tree, you can create one tree object to store Process objects and another tree object to store ints. You can’t store both ints and Processes in the same tree. This restriction is a direct result of the type-safe nature of templates.

Another possible disadvantage of templates is called code bloat: an increased size of the final binary code. Highly specialized code for each template instantiation takes more code than slightly slower generic code. Usually, however, code bloat is not so much of a problem these days.

Templates vs. Inheritance

Section titled “Templates vs. Inheritance”Programmers sometimes find it tricky to decide whether to use templates or inheritance. The following are some tips to help you make the decision.

Use templates when you want to provide identical functionality for different types. For example, if you want to write a generic sorting algorithm that works on any type, use a function template. If you want to create a container that can store any type, use a class template. The key concept is that the class- or function template treats all types the same. However, if required, templates can be specialized for specific types to treat those types differently. Template specialization is discussed in Chapter 12.

When you want to provide different behaviors for related types, use inheritance. For example, in a shape-drawing application, use inheritance to support different shapes such as a circle, a square, a line, and so on. The specific shapes then derive from, for example, a Shape base class.

Another difference between templates and inheritance is that templates are processed at compile time; thus, all involved types must be known at compile time. This results in compile-time polymorphism. With inheritance, you get run-time polymorphism.

Note that you can combine inheritance and templates. You could write a class template that derives from a base class template. Chapter 12 covers the details of the template syntax.

Provide Appropriate Checks and Safeguards

Section titled “Provide Appropriate Checks and Safeguards”When you design code with reuse in mind, you need to pay special attention to make sure the code is safe for use in different use cases, not just the use case at hand.

There are two opposite styles for designing safe code. The optimal programming style is probably using a healthy mix of both of them. The first is called design-by-contract, which means that the documentation for a function or a class represents a contract with a detailed description of what the responsibility of the client code is and what the responsibility of your function or class is. There are three important aspects of design-by-contract: preconditions, postconditions, and invariants. Preconditions list the conditions that client code must satisfy before calling a function. Postconditions list the conditions that must be satisfied by the function when it has finished executing. Finally, invariants list the conditions that must be satisfied during the whole execution of the function.

Design-by-contract is often used in the Standard Library. For example, std::vector defines a contract for using the array notation to get a certain element from a vector. The contract states that no bounds checking is performed, but that this is the responsibility of the client code. In other words, a precondition for using array notation to get elements from a vector is that the given index is valid. This is done to increase performance for client code that knows their indices are within bounds.

The second style is that you design your functions and classes to be as safe as possible. The most important aspect of this guideline is to perform error checking in your code. For example, if your random number generator requires a seed to be in a specific range, don’t just trust the user to pass a valid seed. Check the value that is passed in, and reject the call if it is invalid. As a second example, next to the design-by-contract array notation for retrieving an element from a vector, it also defines an at() member function to get a specific element while performing bounds checking. If the user provides an invalid index, at() throws an exception. So, client code can choose whether it uses the array notation without bounds checking, or at() with bounds checking.

As an analogy, consider an accountant who prepares income tax returns. When you hire an accountant, you provide them with all your financial information for the year. The accountant uses this information to fill out forms from the IRS1. However, the accountant does not blindly fill out your information on the form, but instead makes sure the information makes sense. For example, if you own a house but forget to specify the property tax you paid, the accountant will remind you to supply that information. Similarly, if you say that you paid $12,000 in mortgage interest but made only $15,000 gross income, the accountant might gently ask you if you provided the correct numbers (or at least recommend more affordable housing).

You can think of the accountant as a “program” where the input is your financial information and the output is an income tax return. However, the value added by an accountant is not just that they fill out the forms. You also choose to employ an accountant because of the checks and safeguards that they provide. Similarly in programming, you could provide as many checks and safeguards as possible in your implementations.

There are several techniques and language features that help you to write safe code and to incorporate checks and safeguards in your programs. To report errors to client code, you can for example return an error code, a distinct value like false or nullptr, or an std::optional as introduced in Chapter 1. Alternatively, you can throw an exception to notify client code of any errors. Chapter 14, “Handling Errors,” covers exceptions in detail.

Design for Extensibility

Section titled “Design for Extensibility”You should strive to design your classes in such a way that they can be extended by deriving another class from them, but they should be closed for modification; that is, the behavior should be extendable without you having to modify its implementation. This is called the open/closed principle (OCP).

As an example, suppose you start implementing a drawing application. The first version should only support squares. Your design contains two classes: Square and Renderer. The former contains the definition of a square, such as the length of its sides. The latter is responsible for drawing the squares. You come up with something as follows:

class Square { /* Details not important for this example. */ };

class Renderer{ public: void render(const vector<Square>& squares) { for (auto& square : squares) { /* Render this square object… */ } }};Next, you add support for circles, so you create a Circle class:

class Circle { /* Details not important for this example. */ };To be able to render circles, you have to modify the render() member function of the Renderer class. You decide to change it as follows:

void Renderer::render(const vector<Square>& squares, const vector<Circle>& circles){ for (auto& square : squares) { /* Render this square object… */ } for (auto& circle : circles) { /* Render this circle object… */ }}While doing this, you feel there is something wrong, and you are correct! To extend the functionality to add support for circles, you have to modify the current implementation of render(), so it’s not closed for modifications.

Your design in this case could use inheritance. Here is a possible design using inheritance:

class Shape{ public: virtual void render() = 0;};

class Square : public Shape{ public: void render() override { /* Render square… */ } // Other members not important for this example.};

class Circle : public Shape{ public: void render() override { /* Render circle… */ } // Other members not important for this example.};

class Renderer{ public: void render(const vector<Shape*>& objects) { for (auto* object : objects) { object->render(); } }};With this design, if you want to add support for a new type of shape, you just need to write a new class that derives from Shape and that implements the render() member function. You don’t need to modify anything in the Renderer class. So, this design can be extended without having to modify the existing code; that is, it’s open for extension and closed for modification.

Design Usable Interfaces

Section titled “Design Usable Interfaces”In addition to abstracting and structuring your code appropriately, designing for reuse requires you to focus on the interface with which programmers interact. Even if you have the most beautiful and most efficient implementation, your library will not be any good if it has a wretched interface.

Note that every component in your program should have good interfaces, even if you don’t intend them to be used in multiple programs. First, you never know when something will be reused. Second, a good interface is important even for the first use, especially if you are programming in a group and other programmers must use the code you design and write.

In C++, a class’s properties and member functions can each be public, protected, or private. Making a property or member function public means that any code can access it; protected means that only the class itself and its derived classes can access it; private is a stricter control, which means that not only is the property or member function locked for other code, but even derived classes don’t have access. Note that access specifiers are at the class level, not at the object level. This means that a member function of a class can access, for example, private properties or private member functions of other objects of the same class.

Designing the exposed interface is all about choosing what to make public. You should view the exposed interface design as a process. The main purpose of interfaces is to make the code easy to use, but some interface techniques can help you follow the principle of generality as well.

Consider the Audience

Section titled “Consider the Audience”The first step in designing an exposed interface is to consider whom you are designing it for. Is your audience another member of your team? Is this an interface that you will personally be using? Is it something that a programmer external to your company will use? Perhaps a customer or an offshore contractor? In addition to determining who will be coming to you for help with the interface, this should shed some light on some of your design goals.

If the interface is for your own use, you probably have more freedom to iterate on the design. As you’re making use of the interface, you can change it to suit your own needs. However, you should keep in mind that roles on an engineering team change, and it is quite likely that, someday, others will be using this interface as well.

Designing an interface for other internal programmers to use is slightly different. In a way, your interface becomes a contract with them. For example, if you are implementing the data store component of a program, others are depending on that interface to support certain operations. You will need to find out all of the things that the rest of the team wants your class to do. Do they need versioning? What types of data can they store?

When designing interfaces for an external customer, ideally the external customer should be involved in specifying what functionality your interfaces expose, just as when designing interfaces for internal customers. You’ll need to consider both the specific features they want as well as what customers might want in the future. The terminology used in the interface will have to correspond to the terms that the customer is familiar with, and the documentation will have to be written with that audience in mind. Inside jokes, codenames, and programmer slang should be left out of your design.

Whether your interface is for internal programmers or external customers, the interface is a contract. If the interface is agreed upon before coding begins, you’ll receive groans from users of your interface if you decide to change it after code has been written.

The audience for which you are designing an interface also impacts how much time you should invest in the design. For example, if you are designing an interface with just a couple of member functions that will be used only in a few places by a few users, then it could be acceptable to modify the interface later. However, if you are designing a complex interface or an interface that will be used by many users, then you should spend more time on the design and do your best to prevent having to modify the interface once users start using it. This is what is known as Hyrum’s law (see www.hyrumslaw.com).

Consider the Purpose

Section titled “Consider the Purpose”There are many reasons for writing an interface. Before putting any code on paper or even deciding on what functionality you’re going to expose, you need to understand the purpose of the interface.

Application Programming Interface

Section titled “Application Programming Interface”An application programming interface (API) is an externally visible mechanism to extend a product or use its functionality within another context. If an internal interface is a contract, an API is closer to a set-in-stone law. Once people who don’t even work for your company are using your API, they don’t want it to change unless you’re adding new features that will help them. So, care should be given to planning the API and discussing it with customers before making it available to them.

The main trade-off in designing an API is usually ease of use versus flexibility. Because the target audience for the interface is not familiar with the internal working of your product, the learning curve to use the API should be gradual. After all, your company is exposing this API to customers because the company wants it to be used. If it’s too difficult to use, the API is a failure. Flexibility often works against this. Your product may have a lot of different uses, and you want the customer to be able to leverage all the functionality you have to offer. However, an API that lets the customer do anything that your product can do may be too complicated.

As a common programming adage goes, “A good API makes the common case easy and the advanced/unlikely case possible.” That is, APIs should have a simple learning curve. The things that most programmers will want to do should be accessible. However, the API should allow for more advanced usage, and it’s acceptable to trade off complexity of the rare case for simplicity of the common case. The “Design Interfaces That Are Easy to Use” section later in this chapter discusses this strategy in detail with a number of concrete tips to follow for your designs.

Utility Class or Library

Section titled “Utility Class or Library”Often, your task is to develop some particular functionality for general use elsewhere in the application, for example a logging class. In this case, the interface is somewhat easier to decide on because you tend to expose most or all of the functionality, ideally without giving too much away about its implementation. Generality is an important issue to consider. Because the class or library is general purpose, you’ll need to take the possible set of use cases into account in your design.

Subsystem Interface

Section titled “Subsystem Interface”You may be designing the interface between two major subsystems of the application, such as the mechanism for accessing a database. In these cases, separating the interface from the implementation is paramount for a number of reasons.

One of the most important reasons is mockability. In testing scenarios, you will want to replace a certain implementation of an interface with another implementation of the same interface. For example, when writing test code for a database interface, you might not want to access a real database. An interface implementation accessing a real database could be replaced with one simulating all database access.

Another reason is flexibility. Even besides testing scenarios, you might want to provide several different implementations of a certain interface that can be used interchangeably. For example, you might want to replace a database interface implementation that uses a MySQL server database, with an implementation that uses a SQL Server database. You might even want to switch between different implementations at run time.

Yet another reason: by finishing the interface first, other programmers can already start programming against your interface before your implementation is complete.

When working on a subsystem, first think about what its main purpose is. Once you have identified the main task your subsystem is charged with, think about specific uses and how it should be presented to other parts of the code. Try to put yourself in their shoes and not get bogged down in implementation details.

Component Interface

Section titled “Component Interface”Most of the interfaces you define will probably be smaller than a subsystem interface or an API. These will be classes that you use within other code that you’ve written. In these cases, the main pitfall occurs when your interface evolves gradually and becomes unruly. Even though these interfaces are for your own use, think of them as though they weren’t. As with a subsystem interface, consider the main purpose of each class and be cautious of exposing functionality that doesn’t contribute to that purpose.

Design Interfaces That Are Easy to Use

Section titled “Design Interfaces That Are Easy to Use”Your interfaces should be easy to use. That doesn’t mean that they must be trivial, but they should be as simple and intuitive as the functionality allows. This follows the KISS principle: keep it simple, stupid. You shouldn’t require consumers of your library to wade through pages of source code or documentation in order to use a simple data structure or to go through contortions in their code to obtain the functionality they need. This section provides four specific strategies for designing interfaces that are easy to use.

Follow Familiar Ways of Doing Things

Section titled “Follow Familiar Ways of Doing Things”The best strategy for developing easy-to-use interfaces is to follow standard and familiar ways of doing things. When people encounter an interface similar to something they have used in the past, they will understand it better, adopt it more readily, and be less likely to use it improperly.

For example, suppose that you are designing the steering mechanism of a car. There are a number of possibilities: a joystick, two buttons for moving left or right, a sliding horizontal lever, or a good old steering wheel. Which interface do you think would be easiest to use? Which interface do you think would sell the most cars? Consumers are familiar with steering wheels, so the answer to both questions is, of course, the steering wheel. Even if you developed another mechanism that provided superior performance and safety, you would have a tough time selling your product, let alone teaching people how to use it. When you have a choice between following standard interface models and branching out in a new direction, it’s usually better to stick to the interface to which people are accustomed.

Innovation is important, of course, but you should focus on innovation in the underlying implementation, not in the interface. For example, consumers are excited about the innovative fully electric engine in some car models. These cars are selling well in part because the interface to use them is identical to cars with standard gasoline engines.

Applied to C++, this strategy implies that you should develop interfaces that follow standards to which C++ programmers are accustomed. For example, C++ programmers expect a constructor and destructor of a class to initialize and clean up an object, respectively (both discussed in details in Chapter 8, “Gaining Proficiency with Classes and Objects”). If you need to “reinitialize” an existing object, a standard way is to just assign a newly constructed object to it. When you design your classes, you should follow these standards. If you require programmers to call initialize() and cleanup() member functions for initialization and cleanup instead of placing that functionality in the constructor and destructor, you will confuse everyone who tries to use your class. Because your class behaves differently from other C++ classes, programmers will take longer to learn how to use it and will be more likely to use it incorrectly by forgetting to call initialize() or cleanup().

C++ provides a language feature called operator overloading that can help you develop easy-to-use interfaces for your objects. Operator overloading allows you to write classes such that the standard operators work on them just as they work on built-in types like int and double. For example, you can write a Fraction class that allows you to add, subtract, and print fractions like this:

Fraction f1 { 3, 4 };Fraction f2 { 1, 2 };Fraction sum { f1 + f2 };Fraction diff { f1 – f2 };println("{} {}", f1, f2);Contrast that with the same behavior using member function calls:

Fraction f1 { 3, 4 };Fraction f2 { 1, 2 };Fraction sum { f1.add(f2) };Fraction diff { f1.subtract(f2) };f1.print();print(" ");f2.print();println("");As you can see, operator overloading allows you to provide an easier-to-use interface for your classes. However, be careful not to abuse operator overloading. It’s possible to overload the + operator so that it implements subtraction and the – operator so that it implements multiplication. Those implementations would be counterintuitive. This does not mean that each operator should always implement exactly the same behavior. For example, the string class implements the + operator to concatenate strings, which is an intuitive interface for string concatenation. See Chapters 9 and 15, “Overloading C++ Operators,” for details on operator overloading.

Don’t Omit Required Functionality

Section titled “Don’t Omit Required Functionality”As you are designing your interface, keep in mind what the future holds. Is this a design you will be locked into for years? If so, you might need to leave room for expansion by coming up with a plug-in architecture. Do you have evidence that people will try to use your interface for purposes other than what it was designed for? Talk to them and get a better understanding of their use case. The alternative is rewriting it later or, worse, attaching new functionality haphazardly and ending up with a messy interface. Be careful, though! Speculative generality is yet another pitfall. Don’t design the be-all, end-all logging class if the future uses are unclear, because it might unnecessarily complicate the design, the implementation, and its public interface.

This strategy is twofold. First, include interfaces for all behaviors that clients could need. That might sound obvious at first. Returning to the car analogy, you would never build a car without a speedometer for the driver to view their speed! Similarly, you would never design a Fraction class without a mechanism for client code to access the nominator and denominator values.

However, other possible behaviors might be more obscure. This strategy requires you to anticipate all the uses to which clients might put your code. If you are thinking about the interface in one particular way, you might miss functionality that could be needed when clients use it differently. For example, suppose that you want to design a game board class. You might consider only the typical games, such as chess, and decide to support a maximum of one game piece per spot on the board. However, what if you later decide to write a backgammon game, which allows multiple pieces in one spot on the board? By precluding that possibility, you have ruled out the use of your game board as a backgammon board.

Obviously, anticipating every possible use for your library is difficult, if not impossible. Don’t feel compelled to agonize over potential future uses in order to design the perfect interface. Just give it some thought and do the best you can.

The second part of this strategy is to include as much functionality in the implementation as possible. Don’t require client code to specify information that you already know in the implementation, or could know if you designed it differently. For example, if your library requires a temporary file, don’t make the clients of your library specify that path. They don’t care what file you use; find some other way to determine an appropriate temporary file path.

Furthermore, don’t require library users to perform unnecessary work to amalgamate results. If your random number library uses a random number algorithm that calculates the low-order and high-order bits of a random number separately, combine all bits into one number before giving it to the user.

Present Uncluttered Interfaces

Section titled “Present Uncluttered Interfaces”To avoid omitting functionality in their interfaces, some programmers go to the opposite extreme: they include every possible piece of functionality imaginable. Programmers who use the interfaces are never left without the means to accomplish a task. Unfortunately, the interface might be so cluttered that they never figure out how to do it! Such interfaces are called fat interfaces.

Don’t provide unnecessary functionality in your interfaces; keep them clean and simple. It might appear at first that this guideline directly contradicts the previous strategy of not omitting necessary functionality. Although one strategy to avoid omitting functionality would be to include every imaginable interface, that is not a sound strategy. You should include necessary functionality and omit useless or counterproductive interfaces.

Consider cars again. You drive a car by interacting with only a few components: the steering wheel, the brake and accelerator pedals, the gearshift, the mirrors, the speedometer, and a few other dials on your dashboard. Now, imagine a car dashboard that looked like an airplane cockpit, with hundreds of dials, levers, monitors, and buttons. It would be unusable! Driving a car is so much easier than flying an airplane that the interface can be much simpler: You don’t need to view your altitude, communicate with control towers, or control the myriad components in an airplane such as the wings, engines, and landing gear.

A fat interface can be avoided by breaking up the interface into several smaller ones. Alternatively, the façade design pattern can be used to provide an easier interface or interfaces on top of a fat interface. For example, a fat car interface would include everything from simple actions such as accelerating, braking, and turning, to more advanced functionality, such as numerous options for tuning the performance of the engine, and many more. A better design is to provide multiple easier to use interfaces: one for basic operations such as accelerating, braking, and turning; another one to provide access to the engine tuning options; and many more.

Additionally, from the library development perspective, smaller libraries are easier to maintain. If you try to make everyone happy, then you have more room to make mistakes, and if your implementation is complicated enough so that everything is intertwined, even one mistake can render the library useless.

Unfortunately, the idea of designing uncluttered interfaces looks good on paper, but is remarkably hard to put into practice. The rule is ultimately subjective: you decide what’s necessary and what’s not. Of course, your clients will for sure tell you when you get it wrong!

Provide Documentation

Section titled “Provide Documentation”Regardless of how easy you make your interfaces to use, you should supply documentation for their use. You can’t expect programmers to use your library properly unless you tell them how to do it. Think of your library or code as a product for other programmers to consume. Your product should have documentation explaining its proper use.

There are two ways to provide documentation for your interfaces: comments in the interfaces themselves and external documentation. You should strive to provide both. Most public APIs provide only external documentation: comments are a scarce commodity in many of the standard Unix and Windows header files. In Unix, the documentation usually comes in the form of man pages. In Windows, the documentation usually accompanies the integrated development environment or is available on the Internet.

Despite that most APIs and libraries omit comments in the interfaces themselves, I actually consider this form of documentation the most important. You should never give out a “naked” module or header file that contains only code. Even if your comments repeat exactly what’s in the external documentation, it is less intimidating to look at a module or header file with friendly comments than one with only code. Even the best programmers still like to see written language every so often! Chapter 3 gives concrete tips for what to comment and how to write comments, and also explains that there are tools available that can write external documentation for you based on the comments you write in your interfaces.

Design General-Purpose Interfaces

Section titled “Design General-Purpose Interfaces”The interfaces should be general purpose enough that they can be adapted to a variety of tasks. If you encode specifics of one application in a supposedly general interface, it will be unusable for any other purpose. Here are some guidelines to keep in mind.

Provide Multiple Ways to Perform the Same Functionality

Section titled “Provide Multiple Ways to Perform the Same Functionality”To satisfy all your “customers,” it is sometimes helpful to provide multiple ways to perform the same functionality. Use this technique judiciously, however, because over-application can easily lead to cluttered interfaces.

Consider cars again. Most new cars these days provide remote keyless entry systems, with which you can unlock your car by pressing a button on a key fob. However, these cars often provide a standard key that you can use to physically unlock the car, for example, when the battery in the key fob is drained. Although these two methods are redundant, most customers appreciate having both options.

Sometimes there are similar situations in interface design. Remember from earlier in this chapter, std::vector provides two member functions to get access to a single element at a specific index. You can use either the at() member function, which performs bounds checking, or array notation, which does not. If you know your indices are valid, you can use array notation and forgo the overhead that at() incurs due to bounds checking.

Note that this strategy should be considered an exception to the “uncluttered” rule in interface design. There are a few situations where the exception is appropriate, but you should most often follow the uncluttered rule.

Provide Customizability

Section titled “Provide Customizability”To increase the flexibility of your interfaces, provide customizability. Customizability can be as simple as allowing a client to turn error logging on or off. The basic premise of customizability is that it allows you to provide the same basic functionality to every client but to give clients the ability to tweak it slightly.

One way to accomplish this is through the use of interfaces to invert dependency relationships, also called dependency inversion principle (DIP). Dependency injection is one implementation of this principle. Chapter 4, “Designing Professional C++ Programs,” briefly mentions an example of an ErrorLogger service. You should define an ErrorLogger interface and use dependency injection to inject concrete implementations of this interface into each component that wants to use the ErrorLogger service.

You can allow greater customizability through callbacks and template parameters. For example, you could allow clients to set their own error-handling callbacks. Chapter 19, “Function Pointers, Function Objects, and Lambda Expressions,” discusses callbacks in detail.

The Standard Library takes this customizability strategy to the extreme and allows clients to specify their own memory allocators for containers. If you want to use this feature, you must write a memory allocator class that follows the Standard Library guidelines and adheres to the required interfaces. Most containers in the Standard Library take an allocator as one of their template parameters. Chapter 25, “Customizing and Extending the Standard Library,” provides more details.

Reconciling Generality and Ease of Use

Section titled “Reconciling Generality and Ease of Use”The two goals of ease of use and generality sometimes appear to conflict. Often, introducing generality increases the complexity of the interfaces. For example, suppose that you need a graph structure in a map program to store cities. In the interest of generality, you might use templates to write a generic map structure for any type, not just cities. That way, if you need to write a network simulator in your next program, you can employ the same graph structure to store routers in the network. Unfortunately, by using templates, you make the interface a little clumsier and harder to use, especially if the potential client is not familiar with templates.

However, generality and ease of use are not mutually exclusive. Although in some cases increased generality may decrease ease of use, it is possible to design interfaces that are both general purpose and straightforward to use.

To reduce complexity in your interfaces while still providing enough functionality, you can provide multiple separate interfaces. This is called the interface segregation principle (ISP). For example, you could write a generic networking library with two separate facets: one presents the networking interfaces useful for games, and the other presents the networking interfaces useful for the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) for web browsing. Providing multiple interfaces also helps with making the commonly used functionality easy to use, while still providing the option for the more advanced functionality. Returning to the map program, you might want to provide a separate interface for clients of the map to specify names of cities in different languages, while making English the default as it is so predominant. That way, most clients will not need to worry about setting the language, but those who want to will be able to do so.

Designing a Successful Abstraction

Section titled “Designing a Successful Abstraction”Experience and iteration are essential to good abstractions. Truly well-designed interfaces come from years of writing and using other abstractions. You can also leverage someone else’s years of writing and using abstractions by reusing existing, well-designed abstractions in the form of standard design patterns. As you encounter other abstractions, try to remember what worked and what didn’t work. What did you find lacking in the Windows file system API you used last week? What would you have done differently if you had written the network wrapper, instead of your co-worker? The best interface is rarely the first one you put on paper, so keep iterating. Bring your design to your peers and ask for feedback. If your company uses code reviews, start by doing a review of the interface specifications before the implementation starts. Don’t be afraid to change the abstraction once coding has begun, even if it means forcing other programmers to adapt. Ideally, they’ll realize that a good abstraction is beneficial to everyone in the long term.

Sometimes you need to evangelize a bit when communicating your design to other programmers. Perhaps the rest of the team didn’t see a problem with the previous design or feels that your approach requires too much work on their part. In those situations, be prepared both to defend your work and to incorporate their ideas when appropriate.

A good abstraction means that the exported interface has only public member functions that are stable and will not change. A specific technique to accomplish this is called the private implementation idiom, or pimpl idiom, and is discussed in Chapter 9.

Beware of single-class abstractions. If there is significant depth to the code you’re writing, consider what other companion classes might accompany the main interface. For example, if you’re exposing an interface to do some data processing, consider also writing a result class that provides an easy way to view and interpret the results.

Always turn properties into member functions. In other words, don’t allow external code to manipulate the data behind your class directly. You don’t want some careless or nefarious programmer to set the height of a bunny object to a negative number. Instead, have a “set height” member function that does the necessary bounds checking.

Iteration is worth mentioning again because it is the most important point. Seek and respond to feedback on your design, change it when necessary, and learn from mistakes.

The SOLID Principles

Section titled “The SOLID Principles”This chapter and the previous one discuss a number of basic principles of object-oriented design. To summarize these principles, they are often abbreviated with an easy-to-remember acronym: SOLID. The following table summarizes the five SOLID principles:

| S | Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) A single component should have a single, well-defined responsibility and should not combine unrelated functionality. |

| O | Open/Closed Principle (OCP) A class should be open to extension, but closed for modification. Inheritance is one way to accomplish this. Other mechanisms are templates, function overloading, and more. In general, we speak about customization points in this context. |

| L | Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) You should be able to replace an instance of an object with an instance of a subtype of that object. Chapter 5 explains this principle in the section “The Fine Line Between Has-A and Is-A” with an example to decide whether the relationship between AssociativeArray and MultiAssociativeArray is a has-a or an is-a relationship. |

| I | Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) Keep interfaces clean and simple. It is better to have many smaller, well-defined single-responsibility interfaces than to have broad, general-purpose interfaces. |

| D | Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) Use interfaces to invert dependency relationships. One way to support the dependency inversion principle is dependency injection, discussed earlier in this chapter and further in Chapter 33, “Applying Design Patterns.” |

SUMMARY

Section titled “SUMMARY”By reading this chapter, you learned how you should design reusable code. You read about the philosophy of reuse, summarized as “write once, use often,” and learned that reusable code should be both general purpose and easy to use. You also discovered that designing reusable code requires you to use abstraction, to structure your code appropriately, and to design good interfaces.

This chapter presented specific tips for structuring your code: to avoid combining unrelated or logically separate concepts, to use templates for generic data structures and algorithms, to provide appropriate checks and safeguards, and to design for extensibility.

This chapter also presented six strategies for designing interfaces: to follow familiar ways of doing things, to not omit required functionality, to present uncluttered interfaces, to provide documentation, to provide multiple ways to perform the same functionality, and to provide customizability. It also discussed how to reconcile the often-conflicting demands of generality and ease of use.

The chapter concluded with SOLID, an easy-to-remember acronym that describes the most important design principles discussed in this and other chapters.

This is the last chapter of the second part of the book, which focuses on discussing design themes at a higher level. The next part delves into the implementation phase of the software engineering process, with details of C++ coding.

EXERCISES

Section titled “EXERCISES”By solving the following exercises, you can practice the material discussed in this chapter. Solutions to all exercises are available with the code download on the book’s website at www.wiley.com/go/proc++6e. However, if you are stuck on an exercise, first reread parts of this chapter to try to find an answer yourself before looking at the solution from the website.

- Exercise 6-1: What does it mean to make the common case easy and the unlikely case possible?

- Exercise 6-2: What is the number-one strategy for reusable code design?

- Exercise 6-3: Suppose you are writing an application that needs to work with information about people. One part of the application needs to keep a list of customers with data such as a list of recent orders, loyalty card number, and so on. Another part of the application needs to keep track of employees of your company that have an employee ID, job title, and so on. To satisfy these requirements, you decide to design a class called

Personthat contains their name, phone number, address, list of recent orders, loyalty card number, salary, employee ID, job title (engineer, senior engineer, …), and more. What do you think of such a class? Are there any improvements that you can think of? - Exercise 6-4: Without looking back to the previous pages, explain what SOLID means.

Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) administers and enforces U.S. federal tax laws. ↩