Random Number Facilities

This chapter discusses how to generate random numbers in C++. Generating good random numbers in software is a complex topic. This chapter does not discuss the complex mathematical formulas involved in generating the actual random numbers; however, it does explain how to generate random numbers using the functionality provided by the Standard Library.

The C++ random number generation library can generate random numbers by using different algorithms and distributions. The library is defined by <random> in the std namespace. It has three big components: engines, engine adapters, and distributions. A random number engine is responsible for generating the actual random numbers and storing the state for generating subsequent random numbers. The distribution determines the range of the generated random numbers and how they are mathematically distributed within that range. A random number engine adapter modifies the results of a random number engine you associate it with.

Before delving into this C++ random number generation library, the old C-style mechanism of generating random numbers and its problems are briefly explained.

C-STYLE RANDOM NUMBER GENERATION

Section titled “C-STYLE RANDOM NUMBER GENERATION”Before C++11, you could generate random numbers using the C-style srand() and rand() functions. The srand() function had to be called once in your application and was used to initialize the random number generator, also called seeding. Usually, the current system time would be used as a seed.

You need to make sure that you use a good-quality seed for your software-based random number generator. If you initialize the random number generator with the same seed every time, you will create the same sequence of random numbers every time. This is why the seed is usually the current system time.

Once the generator is initialized, random numbers could be generated with rand(). The following example shows how to use srand() and rand(). The time() function, defined in <ctime>, returns the system time, usually encoded as the number of seconds since the system’s epoch. The epoch represents the beginning of time.

srand(static_cast<unsigned int>(time(nullptr)));println("{}", rand());A random number within a certain range could be generated with the following function:

int getRandom(int min, int max){ return static_cast<int>(rand() % (max + 1UL - min)) + min;}The old C-style rand() function generates random numbers in the range 0 to RAND_MAX, which is defined by the standard to be at least 32,767. You cannot generate random numbers larger than RAND_MAX. On some systems, for example GCC, RAND_MAX is 2,147,483,647, which equals the maximum value of a signed integer. To prevent arithmetic overflow on such systems, the formula in getRandom() uses unsigned long calculations, due to the use of 1UL instead of just 1.

Additionally, the low-order bits of rand() are often not very random, which means that using the previous getRandom() function to generate a random number in a small range, such as 1 to 6, will not result in good randomness.

Besides generating bad-quality random numbers, the old srand() and rand() functions don’t offer much in terms of flexibility either. You cannot, for example, change the distribution of the generated random numbers. In conclusion, it’s highly recommended to stop using srand() and rand() and start using the classes from <random> explained in the upcoming sections.

RANDOM NUMBER ENGINES

Section titled “RANDOM NUMBER ENGINES”The first component of the modern C++ random number generation library is a random number engine, responsible for generating the actual random numbers. As mentioned, everything is defined in <random>.

The following random number engines are available:

random_devicelinear_congruential_enginemersenne_twister_enginesubtract_with_carry_engine

The random_device engine is not a software-based generator; it is a special engine that requires a piece of hardware attached to your computer that generates truly non-deterministic random numbers, for example, by using the laws of physics. A classic mechanism measures the decay of a radioactive isotope by counting alpha-particles-per-time-interval, but there are many other kinds of physics-based random-number generators, including measuring the “noise” of reverse-biased diodes (thus eliminating the concerns about radioactive sources in your computer). The details of these mechanisms fall outside the scope of this book. If no such device is attached to the computer, random_device is free to use one of the software algorithms. The choice of algorithm is up to the library designer. Luckily, most modern computers have proper support for a true random_device.

The quality of a random number generator is measured by its entropy. The entropy() member function of the random_device engine returns 0.0 if it is using a software-based pseudorandom number generator and returns a non-zero value if it is using a hardware device. The non-zero value is an estimate of the entropy of the hardware device.

Using a random_device engine is straightforward:

random_device rnd;println("Entropy: {}", rnd.entropy());println("Min value: {}, Max value: {}", rnd.min(), rnd.max());println("Random number: {}", rnd());A possible output of this program could be as follows:

Entropy: 32Min value: 0, Max value: 4294967295Random number: 3590924439A random_device is much slower than a pseudorandom number engine. Therefore, if you need to generate a lot of random numbers, use a pseudorandom number engine and generate a seed for it with a random_device. This is demonstrated in the section “Generating Random Numbers” later in this chapter.

Next to the random_device engine, there are three pseudorandom number engines:

- Linear congruential engine: Requires a minimal amount of memory to store its state. The state is a single integer containing the last generated random number or the initial seed if no random number has been generated yet. The period of this engine depends on an algorithmic parameter and can be up to 264 but is usually less. For this reason, the linear congruential engine should not be used when you need high-quality random numbers.

- Mersenne twister: Of the three pseudorandom number engines, this one generates the highest quality of random numbers. The period of a Mersenne twister is a Mersenne prime, which is a prime number one less than a power of two. This period is much bigger than the period of a linear congruential engine. The memory required to store the state of a Mersenne twister also depends on its parameters but is much larger than the single integer state of the linear congruential engine. For example, the predefined Mersenne twister

mt19937has a period of 219937−1, while the state contains 625 integers or 2.5 kilobytes. It is also one of the fastest engines. - Subtract with carry engine: Requires a state of around 100 bytes; however, the quality of the generated random numbers is less than that of the numbers generated by the Mersenne twister, and it is also slower than the Mersenne twister.

The mathematical details of the engines and of the quality of random numbers fall outside the scope of this book. If you want to know more about these topics, you can consult a reference from the “Random Numbers” section in Appendix B, “Annotated Bibliography.”

The random_device engine is easy to use and doesn’t require any parameters. However, creating an instance of one of the three pseudorandom number generators requires you to specify a number of mathematical parameters, which can be daunting. The selection of parameters greatly influences the quality of the generated random numbers. For example, the definition of the mersenne_twister_engine class template looks like this:

template<class UIntType, size_t w, size_t n, size_t m, size_t r, UIntType a, size_t u, UIntType d, size_t s, UIntType b, size_t t, UIntType c, size_t l, UIntType f> class mersenne_twister_engine {…}It requires 14 parameters. The linear_congruential_engine and subtract_with_carry_engine class templates also require a number of such mathematical parameters. For this reason, the standard defines a couple of predefined engines. One example is the mt19937 Mersenne twister, which is defined as follows:

using mt19937 = mersenne_twister_engine<uint_fast32_t, 32, 624, 397, 31, 0x9908b0df, 11, 0xffffffff, 7, 0x9d2c5680, 15, 0xefc60000, 18, 1812433253>;These parameters are all magic, unless you understand the details of the Mersenne twister algorithm. In general, you do not want to modify any of these parameters unless you are an expert in the mathematics of pseudorandom number generators. Instead, I recommend using the predefined type aliases such as mt19937. A complete list of predefined engines is given in a later section.

RANDOM NUMBER ENGINE ADAPTERS

Section titled “RANDOM NUMBER ENGINE ADAPTERS”A random number engine adapter modifies the result of a random number engine you associate it with, which is called the base engine. This is an example of the adapter pattern (see Chapter 33, “Applying design patterns”). The following three adapter templates are defined:

template<class Engine, size_t p, size_t r> class discard_block_engine {…}template<class Engine, size_t w, class UIntT> class independent_bits_engine {…}template<class Engine, size_t k> class shuffle_order_engine {…}The discard_block_engine adapter generates random numbers by discarding some of the values generated by its base engine. It requires three parameters: the engine to adapt, the block size p, and the used block size r. The base engine is used to generate p random numbers. The adapter then discards p-r of those numbers and returns the remaining r numbers.

The independent_bits_engine adapter generates random numbers with a given number of bits w by combining several random numbers generated by the base engine.

The shuffle_order_engine adapter generates the same random numbers that are generated by the base engine but delivers them in a different order. The template parameter k is the size of an internal table used by the adapter. A random number is randomly selected from this table upon request, and then replaced with a new random number generated by the base engine.

Just as with random number engines, a number of predefined engine adapters are available. The next section gives an overview of the predefined engines and engine adapters.

PREDEFINED ENGINES AND ENGINE ADAPTERS

Section titled “PREDEFINED ENGINES AND ENGINE ADAPTERS”As mentioned earlier, it is not recommended to specify your own parameters for pseudorandom number engines and engine adapters, but instead to use one of the standard ones. The C++ Standard Library defines the following predefined generators, all in <random>. They all have complicated template arguments, but it is not necessary to understand those arguments to be able to use them.

| PREDEFINED GENERATOR | CLASS TEMPLATE |

|---|---|

| minstd_rand0 | linear_congruential_engine |

| minstd_rand | linear_congruential_engine |

| mt19937 | mersenne_twister_engine |

| mt19937_64 | mersenne_twister_engine |

| ranlux24_base | subtract_with_carry_engine |

| ranlux48_base | subtract_with_carry_engine |

| ranlux24 | discard_block_engine |

| ranlux48 | discard_block_engine |

| knuth_b | shuffle_order_engine |

| default_random_engine | Implementation-defined |

The default_random_engine is compiler dependent.

The following section gives an example of how to use these predefined engines.

GENERATING RANDOM NUMBERS

Section titled “GENERATING RANDOM NUMBERS”Before you can generate any random number, you first need to create an instance of an engine. If you use a software-based engine, you also need to define a distribution. A distribution is a mathematical formula describing how numbers are distributed within a certain range. The recommended way to create an engine is to use one of the predefined engines discussed in the previous section.

The following example uses the predefined engine called mt19937, using a Mersenne twister engine. This is a software-based generator. Just as with the old rand() generator, a software-based engine must be initialized with a seed. The seed used with srand() was often the current time. In modern C++, it’s recommended to use a random_device to generate a seed. Here is an example:

random_device seeder;mt19937 engine { seeder() };As mentioned earlier, most modern systems have a random_device implementation with proper entropy. If you are not sure that the random_device implementation on the system your code will be running on has proper entropy, then you can use a time-based seed as a fallback:

random_device seeder;const auto seed { seeder.entropy() ? seeder() : time(nullptr) };mt19937 engine { static_cast<mt19937::result_type>(seed) };Next, a distribution is defined. This example uses a uniform integer distribution, for the range 1 to 99. Distributions are explained in detail in the next section, but this uniform distribution is easy enough to use for this example:

uniform_int_distribution<int> distribution { 1, 99 };Once the engine and distribution are defined, random numbers can be generated by calling the function call operator of the distribution and passing the engine as an argument. For this example, this is written as distribution(engine):

println("{}", distribution(engine));As you can see, to generate a random number using a software-based engine, you always need to specify the engine and distribution. The std::bind() utility, introduced in Chapter 19, “Function Pointers, Function Objects, and Lambda Expressions,” can be used to remove the need to specify both the distribution and the engine when generating a random number. The following example uses the same mt19937 engine and uniform distribution as the previous example, but it defines generator by using std::bind() to bind engine as the first argument to distribution(). This way, you can call generator() without any arguments to generate a random number. The example then demonstrates the use of generator() in combination with the constrained ranges::generate() algorithm to fill a vector of ten elements with random numbers. The generate() algorithm is discussed in Chapter 20, “Mastering Standard Library Algorithms.”

auto generator { bind(distribution, engine) };

vector<int> values(10);ranges::generate(values, generator);

println("{:n}", values);Even though you don’t know the exact type of generator, it’s still possible to pass generator to another function that wants to use that generator. You have several options: use a parameter of type std::function<int()> or use a function template. The previous example can be adapted to generate random numbers in a function called fillVector(). Here is an implementation using std::function:

void fillVector(vector<int>& values, const function<int()>& generator){ ranges::generate(values, generator);}Here is a constrained function template variant:

template <invocable T>void fillVector(vector<int>& values, const T& generator){ ranges::generate(values, generator);}This can be simplified using the abbreviated function template syntax:

void fillVector(vector<int>& values, const auto& generator){ ranges::generate(values, generator);}Finally, this function can be used as follows:

vector<int> values(10);fillVector(values, generator);The random number generators are not thread safe. If you need to generate random numbers in multiple threads, you should create a generator in each thread and not share one generator among multiple threads. Chapter 27, “Multithreaded Programming with C++,” introduces multithreading.

RANDOM NUMBER DISTRIBUTIONS

Section titled “RANDOM NUMBER DISTRIBUTIONS”A distribution is a mathematical formula describing how numbers are distributed within a certain range. The random number generator library comes with the following distributions that can be used with pseudorandom number engines to define the distribution of the generated random numbers. It’s a compacted representation. The first line of each distribution is the name and class template parameters, if any. The next lines are a constructor for the distribution. Only one constructor for each distribution is shown to give you an idea of the class. Consult a Standard Library Reference (see Appendix B) for a detailed list of all constructors and member functions of each distribution.

These are the available uniform distributions:

template<class IntType = int> class uniform_int_distribution uniform_int_distribution(IntType a = 0, IntType b = numeric_limits<IntType>::max());template<class RealType = double> class uniform_real_distribution uniform_real_distribution(RealType a = 0.0, RealType b = 1.0);These are the available Bernoulli distributions (the first one generates random Boolean values, while the last three generate random non-negative integer values, all of them according to the discrete probability distribution):

class bernoulli_distribution bernoulli_distribution(double p = 0.5);template<class IntType = int> class binomial_distribution binomial_distribution(IntType t = 1, double p = 0.5);template<class IntType = int> class geometric_distribution geometric_distribution(double p = 0.5);template<class IntType = int> class negative_binomial_distribution negative_binomial_distribution(IntType k = 1, double p = 0.5);These are the available Poisson distributions (generate random non-negative integer values according to the discrete probability distribution):

template<class IntType = int> class poisson_distribution poisson_distribution(double mean = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class exponential_distribution exponential_distribution(RealType lambda = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class gamma_distribution gamma_distribution(RealType alpha = 1.0, RealType beta = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class weibull_distribution weibull_distribution(RealType a = 1.0, RealType b = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class extreme_value_distribution extreme_value_distribution(RealType a = 0.0, RealType b = 1.0);These are the available normal distributions:

template<class RealType = double> class normal_distribution normal_distribution(RealType mean = 0.0, RealType stddev = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class lognormal_distribution lognormal_distribution(RealType m = 0.0, RealType s = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class chi_squared_distribution chi_squared_distribution(RealType n = 1);template<class RealType = double> class cauchy_distribution cauchy_distribution(RealType a = 0.0, RealType b = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class fisher_f_distribution fisher_f_distribution(RealType m = 1, RealType n = 1);template<class RealType = double> class student_t_distribution student_t_distribution(RealType n = 1);These are the available sampling distributions:

template<class IntType = int> class discrete_distribution discrete_distribution(initializer_list<double> wl);template<class RealType = double> class piecewise_constant_distribution template<class UnaryOperation> piecewise_constant_distribution(initializer_list<RealType> bl, UnaryOperation fw);template<class RealType = double> class piecewise_linear_distribution template<class UnaryOperation> piecewise_linear_distribution(initializer_list<RealType> bl, UnaryOperation fw);Each distribution requires a set of parameters. As before, explaining all these mathematical parameters is outside the scope of this book. The rest of this section includes a couple of examples to explain the impact of a distribution on the generated random numbers.

Distributions are easiest to understand when you look at a graphical representation of them. The following code generates one million random numbers between 1 and 99 and keeps track of how many times a certain number is randomly generated in a histogram. The counters are stored in a map where the key is a number between 1 and 99, and the value associated with a key is the number of times that that key has been selected randomly. After the loop, the results are written to a semicolon-separated values file (CSV), which can be opened in a spreadsheet application.

const unsigned int Start { 1 };const unsigned int End { 99 };const unsigned int Iterations { 1'000'000 };

// Uniform distributed Mersenne Twister.random_device seeder;mt19937 engine { seeder() };uniform_int_distribution<int> distribution { Start, End };auto generator { bind(distribution, engine) };map<int, int> histogram;for (unsigned int i { 0 }; i < Iterations; ++i) { int randomNumber { generator() }; // Search map for a key=randomNumber. If found, add 1 to the value associated // with that key. If not found, add the key to the map with value 1. ++(histogram[randomNumber]);}

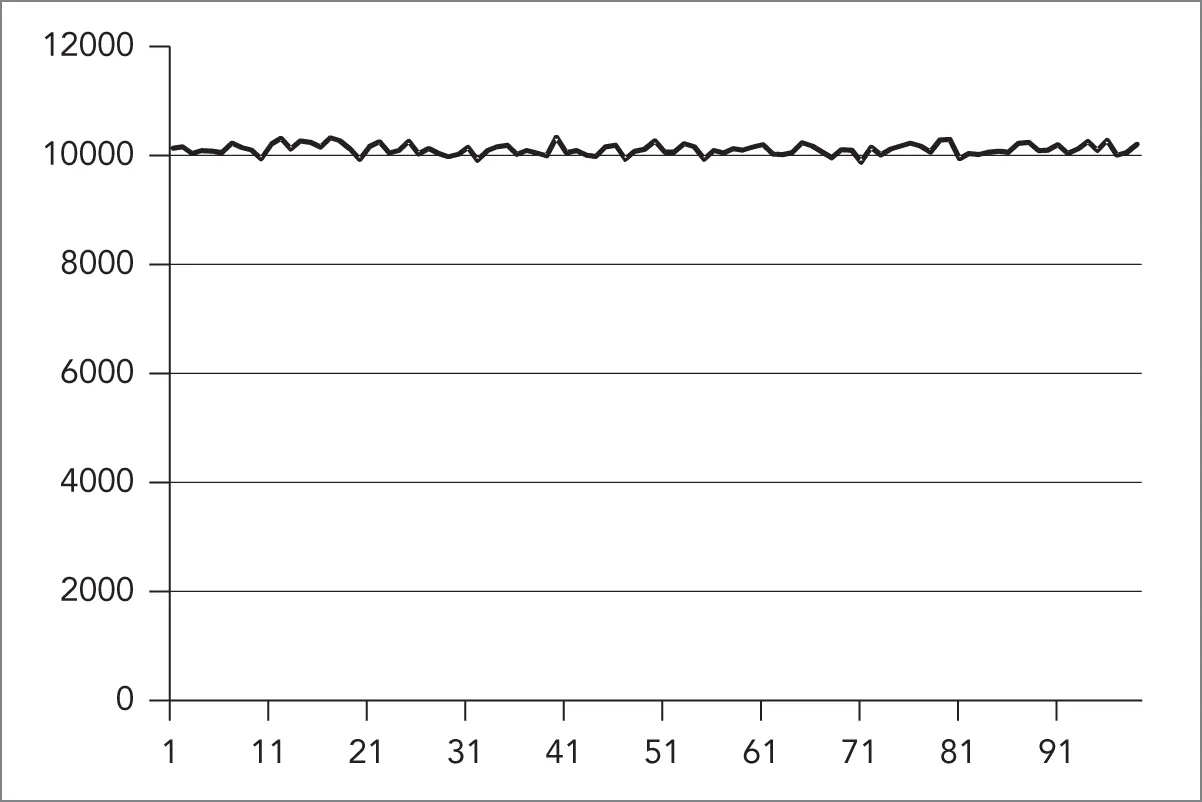

// Write to a CSV file.ofstream of { "res.csv" };for (unsigned int i { Start }; i <= End; ++i) { of << i << ";" << histogram[i] << endl;}The resulting data can then be used to generate a graphical representation. Figure 23.1 shows a graph of the generated histogram.

The horizontal axis represents the range in which random numbers are generated. The graph clearly shows that all numbers in the range 1 to 99 are randomly chosen around 10,000 times and that the distribution of the generated random numbers is uniform across the entire range.

[^FIGURE 23.1]

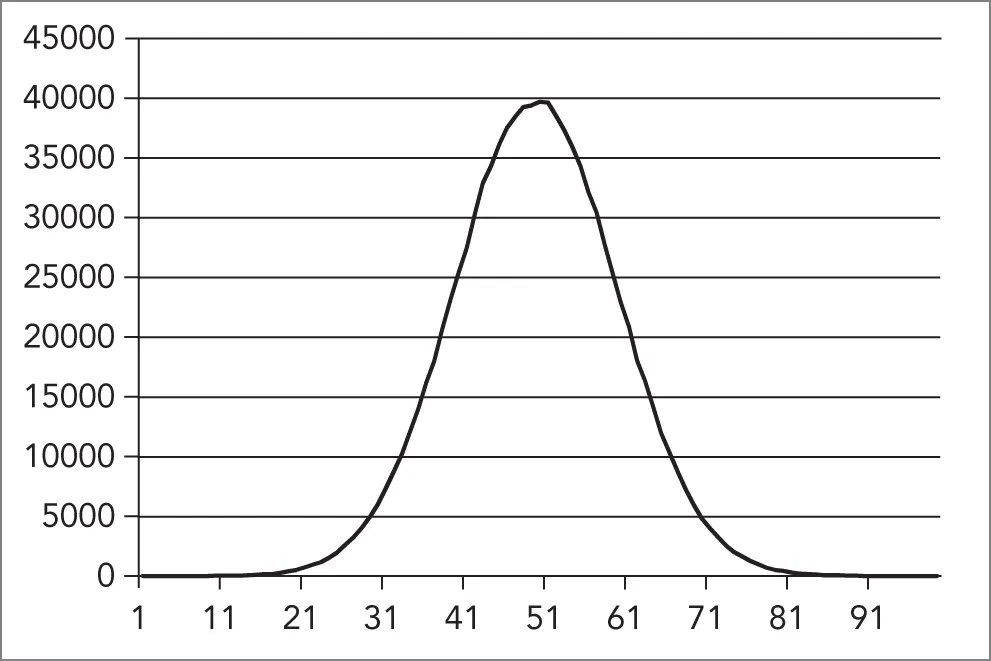

The example can be modified to generate random numbers according to a normal distribution instead of a uniform distribution. Only two small changes are required. First, you need to modify the creation of the distribution as follows:

normal_distribution<double> distribution { 50, 10 };Because normal distributions use doubles instead of integers, you also need to modify the call to generator():

int randomNumber { static_cast<int>(generator()) };Figure 23.2 shows a graphical representation of the random numbers generated according to this normal distribution.

[^FIGURE 23.2]

The graph clearly shows that most of the generated random numbers are around the center of the range. In this example, the value 50 is randomly chosen around 40,000 times, while values like 20 and 80 are chosen only around 500 times.

SUMMARY

Section titled “SUMMARY”In this chapter, you learned how to use the C++ random number generation library provided by the Standard Library to generate good-quality random numbers. You also saw how you can change the distribution of the generated numbers over a given range.

The next chapter is the last chapter of Part 3 of the book and introduces a number of additional vocabulary types that you will use often in your day-to-day coding.

EXERCISES

Section titled “EXERCISES”By solving the following exercises, you can practice the material discussed in this chapter. Solutions to all exercises are available with the code download on the book’s website at www.wiley.com/go/proc++6e. However, if you are stuck on an exercise, first reread parts of this chapter to try to find an answer yourself before looking at the solution from the website.

-

Exercise 23-1: Write a loop asking the user if dice should be thrown or not. If yes, throw a die twice using a uniform distribution and print the two numbers on the screen. If no, stop the program. Use the standard

mt19937Mersenne twister engine. Do not create your random number generator directly in the function where you need it. Instead, write a functioncreateDiceValueGenerator()that creates the correct random number generator object and returns it. -

Exercise 23-2: Modify your solution to Exercise 23-1 to use a

ranlux48engine instead of the Mersenne twister. -

Exercise 23-3: Modify your solution to Exercise 23-1. Instead of directly using the

mt19937Mersenne twister engine, adapt the engine with ashuffle_order_engineadapter. -

Exercise 23-4: Take the source code from earlier in this chapter used to generate histograms to make graphs of a distribution and experiment a bit with different distributions. Try to plot the graphs in a spreadsheet application to see the effects of a distribution. The code can be found in the downloadable source code archive in the folder

Ch23\01_Random. You can take either the07_uniform_int_distribution.cppor the08_normal_distribution.cppfile depending on whether your distribution uses integers or doubles.Bonus: Besides exporting the data to a CSV file, draw the histogram on the standard output console using characters.