Multithreaded Programming with C++

Multithreaded programming is important on computer systems with multiple processor units. It allows you to write a program to use all those processor units in parallel. There are multiple ways for a system to have multiple processor units. The system can have multiple discrete processor chips, each one an independent central processing unit (CPU). Or, the system can have a single discrete processor chip that internally consists of multiple independent CPUs, also called cores. These kinds of processors are called multicore processors. A system can also have a combination of both. Systems with multiple processor units have existed for a long time; however, they were rarely used in consumer systems. Today, all CPU vendors are selling multicore processors, which are being used in everything from servers to consumer computers to smartphones. Because of this proliferation of multicore processors, it is important to know how to write multithreaded applications. A professional C++ programmer needs to know how to write correct multithreaded code to take full advantage of all the available processor units. Writing multithreaded applications used to rely on platform- and operating system–specific APIs. This made it difficult to write platform-independent multithreaded code. C++11 addressed this problem by including a standard threading library.

Multithreaded programming is a complicated subject. This chapter introduces multithreaded programming using the standard threading library, but it cannot go into all of the details due to space constraints. Entire books have been written about developing multithreaded programs. If you are interested in more details, consult one of the references in the multithreading section of Appendix B, “Annotated Bibliography.”

There are also third-party C++ libraries that try to make multithreaded programming more platform independent, such as pthreads and the boost::thread library. However, because these libraries are not part of the C++ standard, they are not discussed in this book.

INTRODUCTION

Section titled “INTRODUCTION”There are three major styles of executing multiple tasks:

- Sequential execution: Each task is executed one after the other.

- Concurrent execution: Multiple tasks can be executing seemingly at the same time, but this can be because the operating system is giving a task a tiny amount of time, known as a time slice, to do some work, then giving another task a time slice to do its work, and so on. This task switching keeps ongoing until tasks are finished.

- Parallel execution: Multiple tasks are truly executing at the same time for example, on multiple processor units.

Multithreaded programming allows you to execute multiple tasks concurrently (perhaps even in parallel). As a result, you can take advantage of the multiple processor units inside virtually all systems today. Two decades ago, the processor market was racing for the highest frequency, which is perfect for single-threaded applications. Around 2005, this race stopped due to a combination of power and heat management problems. Since then, the processor market is racing toward the most cores on a single processor chip. Quad- and octa-core processors are common, but processors with up to 128 and more cores are available.

Similarly, if you look at the processors on graphics cards, called graphical processing units (GPUs), you’ll see that they are massively parallel processors. Today, high-end graphics cards have more than 16,000 cores, a number that keeps increasing rapidly! These graphics cards are used not only for gaming, but also to perform computationally intensive tasks, such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, image and video manipulation, protein folding (useful for discovering new drugs), processing signals as part of the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) project, and so on.

C++98/03 did not have support for multithreaded programming, and you had to resort to third-party libraries or to the multithreading APIs of your target operating system. Since C++11 introduced a standard multithreading library, it became easier to write cross-platform multithreaded applications. However, the current C++ standard targets only CPUs and not GPUs. This might change in the future.

There are two reasons to start writing multithreaded code. First, if you have a computational problem and you manage to separate it into small pieces that can be run in parallel independently from each other, you can expect a huge performance boost when running it on multiple processor units. Second, you can modularize computations along orthogonal axes. For example, you can do long computations in a worker thread instead of blocking the UI thread, so the user interface remains responsive while a long computation occurs in the background.

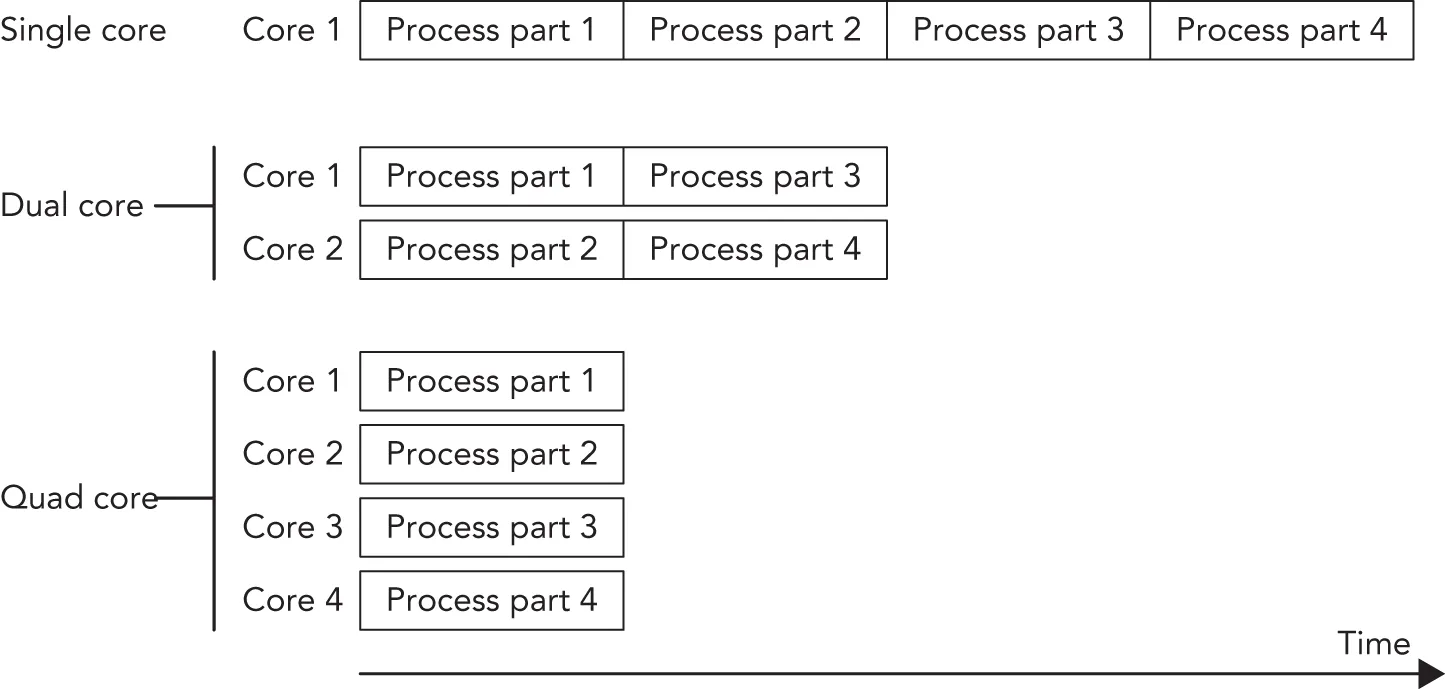

Figure 27.1 shows a situation that is perfectly suited for running in parallel. An example could be the processing of pixels of an image by an algorithm that does not require information about neighboring pixels. The algorithm could split the image into four parts. On a single-core processor, each part would be processed sequentially; on a dual-core processor, two parts would be processed in parallel; and on a quad-core processor, four parts would be processed in parallel, resulting in an almost linear scaling of the performance with the number of cores.

[^FIGURE 27.1]

Of course, it’s not always possible to split the problem into parts that can be executed independently of each other in parallel. However, it can often be made parallel, at least partially, resulting in a performance increase. A difficult part of multithreaded programming is making your algorithm parallel, which is highly dependent on the type of the algorithm. Other difficulties are race conditions, deadlocks, tearing, and false sharing. These are discussed in the following sections. Options for making code thread-safe include:

- Immutable data: Constant data is inherently safe to be accessed by multiple threads.

- Atomic operations: These are low-level types that automatically provide thread-safe operations.

- Mutual exclusion and other synchronization mechanisms: These are used to coordinate access to shared data from multiple threads.

- Thread-local storage: Variables that are marked as

thread_localare local to a thread; other threads don’t have access to them (at least not by default), so they are generally thread-safe.

All these topics are touched upon in this chapter.

Race Conditions

Section titled “Race Conditions”Race conditions can occur when multiple threads want to access any kind of shared resources. Race conditions in the context of memory shared by multiple threads are called data races. A data race can occur when multiple threads access the same variable, and at least one of those threads writes to it. For example, suppose you have a shared variable and one thread increments this value while another thread decrements it. Incrementing and decrementing the value means that the current value needs to be retrieved from memory, incremented or decremented, and stored back in memory. Most processors have INC and DEC instructions to do these operations. On modern x86 processors, these instructions are not atomic, meaning that other instructions can be executed in the middle of the operation, which might cause the code to retrieve a wrong value.

The following table shows the result when the increment is finished before the decrement starts and assumes that the initial value is 1:

| THREAD 1 (INCREMENT) | THREAD 2 (DECREMENT) |

|---|---|

| load value (value = 1) | |

| increment value (value = 2) | |

| store value (value = 2) | |

| load value (value = 2) | |

| decrement value (value = 1) | |

| store value (value = 1) |

The final value stored in memory is 1. When the decrement thread is finished before the increment thread starts, the final value is also 1, as shown in the following table:

| THREAD 1 (INCREMENT) | THREAD 2 (DECREMENT) |

|---|---|

| load value (value = 1) | |

| decrement value (value = 0) | |

| store value (value = 0) | |

| load value (value = 0) | |

| increment value (value = 1) | |

| store value (value = 1) |

However, when the instructions are interleaved, the result is different, as shown in the following table:

| THREAD 1 (INCREMENT) | THREAD 2 (DECREMENT) |

|---|---|

| load value (value = 1) | |

| increment value (value = 2) | |

| load value (value = 1) | |

| decrement value (value = 0) | |

| store value (value = 2) | |

| store value (value = 0) |

The final result in this case is 0. In other words, the effect of the increment operation is lost. This is a data race.

Tearing

Section titled “Tearing”Tearing is a specific case or consequence of a data race. There are two kinds of tearing: torn read and torn write. If a thread has written part of your data to memory, while another part hasn’t been written yet, any other thread reading that data at that exact moment sees inconsistent data: a torn read. If two threads are writing to the data at the same time, one thread might have written part of the data, while another thread might have written another part of the data. The final result will be inconsistent: a torn write.

Deadlocks

Section titled “Deadlocks”If you opt to solve a race condition by using a synchronization mechanism, such as mutual exclusion, you might run into another common problem with multithreaded programming: deadlocks. Two threads are deadlocked if they are both waiting for the other thread to do something. This can be extended to more than two threads. For example, if two threads want to acquire access to a shared resource, they need to ask for permission to access this resource. If one of the threads currently holds the permission to access the resource, but is blocked indefinitely for some other reason, then the other thread will block indefinitely as well when trying to acquire permission for the same resource. One mechanism to acquire permission for a shared resource is called a mutual exclusion object, or mutex for short, discussed in detail later in this chapter. For example, suppose you have two threads and two resources protected with two mutexes, A and B. Both threads acquire permission for both resources, but they acquire the permission in different order. The following table shows this situation in pseudo-code:

| THREAD 1 | THREAD 2 |

|---|---|

| Acquire A Acquire B // … computeRelease BRelease A | Acquire B Acquire A // … compute Release A Release B |

Now, imagine that the code in the two threads is executed in the following order:

- Thread 1: Acquire A (succeeds)

- Thread 2: Acquire B (succeeds)

- Thread 1: Acquire B (waits/blocks, because B is held by thread 2)

- Thread 2: Acquire A (waits/blocks, because A is held by thread 1)

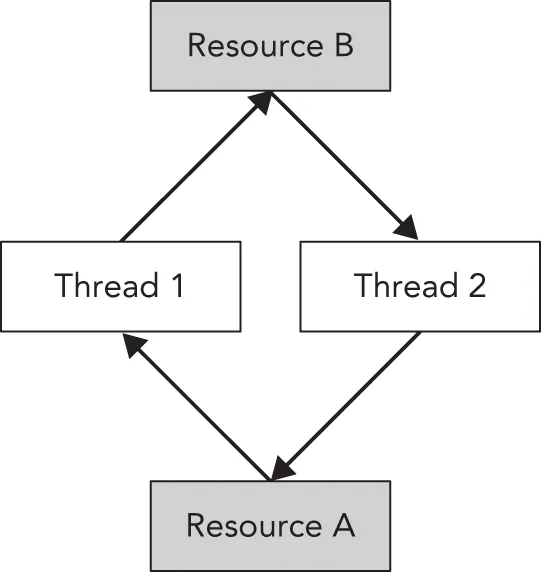

Both threads are now waiting indefinitely in a deadlock situation. Figure 27.2 shows a graphical representation of the deadlock. Thread 1 has acquired permission for resource A and is waiting to acquire permission for resource B. Thread 2 has acquired permission for resource B and is waiting to acquire permission for resource A. In this graphical representation, you see a cycle that depicts the deadlock. Both threads will wait indefinitely.

[^FIGURE 27.2]

It’s best to always acquire permissions in the same order to avoid these kinds of deadlocks. You could also include mechanisms in your program to break these deadlocks. One possible solution is to try for a certain time to acquire permission for a resource. If the permission cannot be obtained within a certain time interval, the thread can stop waiting and possibly release other permissions it is currently holding. The thread can then sleep for a little bit and try again later to acquire all the resources it needs. This mechanism gives other threads the opportunity to acquire necessary permissions and continue their execution. Whether this mechanism works or not depends heavily on your specific deadlock case.

The previous paragraph describes workarounds to avoid deadlocks. These exact workarounds are implemented in the Standard Library by std::lock(), described later in the section “Mutual Exclusion.” This function obtains permission for several resources with one call, without the risk of deadlocks. You should use std::lock() instead of reinventing the same workarounds. However, it’s even better not to get into such a situation in the first place by avoiding having to take multiple locks at once. Ideally, try to avoid patterns that require locking at all.

False Sharing

Section titled “False Sharing”Most caches work with cache lines. For modern CPUs, cache lines are usually 64 bytes. If something needs to be written to a cache line, the entire line needs to be locked. This can bring a serious performance penalty for multithreaded code if your data structure is not properly designed. For example, if two threads are using two different pieces of data, but that data shares a cache line, then when one thread writes something, the other thread is blocked because the entire cache line is locked. Figure 27.3 graphically shows the situation where two threads clearly write to two different blocks of memory while sharing a cache line.

[^FIGURE 27.3]

You can optimize your data structures by using explicit memory alignments to make sure data that is worked on by multiple threads does not share any cache lines. To do this in a portable manner, a constant called hardware_destructive_interference:size, defined in <new>, can be used, which returns you the minimum recommended offset between two concurrently accessed objects to avoid cache line sharing. You can use that value in combination with the alignas keyword to properly align your data.

THREADS

Section titled “THREADS”The C++ threading library, defined in <thread>, makes it easy to launch new threads. You can specify what needs to be executed in the new thread in several ways. You can let the new thread execute a global function, the operator() of a function object, a lambda expression, or even a member function of an instance of some class. The following sections give small examples of all these techniques.

Thread with Function Pointer

Section titled “Thread with Function Pointer”Functions such as CreateThread(), _beginthread(), and so on, on Windows, and pthread_create() with the pthreads library, require that the thread function has only one parameter. On the other hand, a function that you want to use with the standard C++ std::thread class can have as many parameters as you want.

Suppose you have a counter() function accepting two integers: the first representing an ID and the second representing the number of iterations that the function should loop. The body of the function is a single loop that loops the given number of iterations. On each iteration, a message is printed to standard output.

void counter(int id, int numIterations){ for (int i { 0 }; i < numIterations; ++i) { println("Counter {} has value {}", id, i); }}You can launch multiple threads executing this function using std::thread. You can create a thread t1, executing counter() with arguments 1 and 6 as follows:

thread t1 { counter, 1, 6 };The constructor of the thread class is a variadic template, which means that it accepts any number of arguments. Variadic templates are discussed in detail in Chapter 26, “Advanced Templates.” The first argument is a callable object (such as a function pointer—in this example, a pointer to the function counter()) to execute in the new thread. Any subsequent arguments are passed to this callable when execution of the thread starts.

A thread object is said to be joinable if it represents or represented an active thread in the system. Even when the thread has finished executing, a thread object remains in the joinable state. A default-constructed thread object is unjoinable. Before a joinable thread object is destroyed, you need to make sure to call either join() or detach() on it. A call to join() is a blocking call: it waits until the thread has finished its work. A call to detach() detaches a thread object from its underlying OS thread, in which case the OS thread keeps running independently. Both member functions cause the thread to become unjoinable. If a thread object that is still joinable is destroyed, the destructor calls std::terminate(), which abruptly terminates all threads and the application itself. The reason for this behavior is that destroying a thread without joining it is almost certainly a bug, and terminating the program is the best available way for the library to indicate the problem.

The following code launches two threads executing the counter() function. After launching the threads,

join() is called on both threads.

thread t1 { counter, 1, 6 };thread t2 { counter, 2, 4 };t1.join();t2.join();A possible output of this example looks as follows:

Counter 2 has value 0Counter 1 has value 0Counter 1 has value 1Counter 1 has value 2Counter 1 has value 3Counter 1 has value 4Counter 1 has value 5Counter 2 has value 1Counter 2 has value 2Counter 2 has value 3The output on your system will be different, and it will most likely be different every time you run it. This is because two threads are executing the counter() function at the same time, so the output depends on the number of processing cores in your machine and on the thread scheduling of the operating system.

Calling print() or println() from different threads is thread-safe and doesn’t cause any data races. However, if you change the single println() statement in counter() to the following:

print("Counter {} has value {}", id, i);println("");Or:

cout << format("Counter {} has value {}", id, i) << endl;Or:

cout << format("Counter {} has value {}", id, i);cout << endl;Then, even though there are still no data races, output from different threads can be interleaved! This means that the output can be mixed together as follows:

Counter 1 has value 0Counter 2 has value 0

Counter 2 has value 1Counter 2 has value 2Counter 1 has value 1…This can be fixed using synchronization mechanisms, which are discussed later in this chapter.

Thread with Function Object

Section titled “Thread with Function Object”Instead of using function pointers, you can also use a function object to execute in a thread. With the function pointer technique of the previous section, the only way to pass information to the thread is by passing arguments to the function. With function objects, you can add data members to your function object class, which you can initialize and use however you want. The following example first defines a class called Counter, which has two data members: an ID and the number of iterations for the loop. Both variables are initialized with the constructor. To make the Counter class a function object, you need to implement operator(), as discussed in Chapter 19, “Function Pointers, Function Objects, and Lambda Expressions.” The implementation of operator() is the same as the counter() function from the previous section. Here is the code:

class Counter{ public: explicit Counter(int id, int numIterations) : m_id { id }, m_numIterations { numIterations } { }

void operator()() const { for (int i { 0 }; i < m_numIterations; ++i) { println("Counter {} has value {}", m_id, i); } } private: int m_id { 0 }; int m_numIterations { 0 };};Two techniques for initializing threads with a function object are demonstrated in the following code snippet. The first technique uses the uniform initialization syntax. You create an instance of Counter with its constructor arguments and give it to the thread constructor between curly braces. The second technique defines a named instance of Counter and gives this named instance to the constructor of the thread class.

// Using uniform initialization syntax.thread t1 { Counter { 1, 20 } };

// Using named variable.Counter c { 2, 12 };thread t2 { c };

// Wait for threads to finish.t1.join();t2.join();Thread with Lambda

Section titled “Thread with Lambda”Lambda expressions fit nicely with the standard C++ threading library. Here is an example that launches a thread to execute a given lambda expression:

int id { 1 };int numIterations { 5 };thread t1 { [id, numIterations] { for (int i { 0 }; i < numIterations; ++i) { println("Counter {} has value {}", id, i); }} };t1.join();Thread with Member Function Pointer

Section titled “Thread with Member Function Pointer”You can specify a member function of a class to be executed in a thread. The following example defines a basic Request class with a process() member function. The main() function creates an instance of the Request class and launches a new thread, which executes the process() member function of the Request instance req.

class Request{ public: explicit Request(int id) : m_id { id } { } void process() { println("Processing request {}", m_id); } private: int m_id { 0 };};

int main(){ Request req { 100 }; thread t { &Request::process, &req }; t.join();}With this technique, you are executing a member function on a specific object in a separate thread. If other threads are accessing the same object, you need to make sure this happens in a thread-safe way to avoid data races. Mutual exclusion, discussed later in this chapter, can be used as a synchronization mechanism to make it thread-safe.

Thread-Local Storage

Section titled “Thread-Local Storage”The C++ standard supports thread-local storage. With a keyword called thread_local, you can mark any variable as thread-local, which means that each thread will have its own unique copy of the variable, and it will last for the entire duration of the thread. For each thread, the variable is initialized exactly once. For example, the following code defines two global variables, k and n. Every thread shares one—and only one—copy of k, while each thread has its own unique copy of n.

int k;thread_local int n;The following code snippet verifies this. threadFunction() prints the current values for k and n, and then increments them both. The main() function launches a first thread, waits for it to finish, and then launches a second thread.

void threadFunction(int id){ println("Thread {}: k={}, n={}", id, k, n); ++n; ++k;}

int main(){ thread t1 { threadFunction, 1 }; t1.join(); thread t2 { threadFunction, 2 }; t2.join();}From the following output, it’s clear that there is only a single instance of k shared across all threads, while each thread has its own copy of n.

Thread 1: k=0, n=0Thread 2: k=1, n=0The previous paragraphs show how thread_local works for global variables. It also works for static data members of classes and static local variables of functions. Inside a function, and only inside a function, declaring a variable as thread_local implies static, but it’s recommended to be explicit about this. Here are some examples:

static thread_local int x1; // OK, internal linkage (See Chapter 11)thread_local int x2; // OK, external linkage (See Chapter 11)

class Foo{ static thread_local int x3; // OK thread_local int x4; // Error!};

void f(){ static thread_local int x5; // OK thread_local int x6; // OK, implicitly static!}Canceling Threads

Section titled “Canceling Threads”The C++ standard does not include any mechanism for canceling a running thread from another thread. One (partial) solution is to use the jthread class, discussed in the next section. If that’s not an option, then the best way to achieve this is to provide some communication mechanism that the two threads agree upon. The simplest mechanism is to have a shared variable, which the target thread checks periodically to determine if it should terminate. Other threads can set this shared variable to indirectly instruct the thread to shut down. You have to be careful here, because this shared variable is being accessed by multiple threads, of which at least one is writing to the shared variable. To make this thread safe, it’s recommended to use atomic variables or condition variables, both discussed later in this chapter.

Automatically Joining Threads

Section titled “Automatically Joining Threads”As discussed earlier, if a thread instance is destroyed that is still joinable, the C++ runtime calls std::terminate() to terminate the application. <thread> also defines std::jthread, which is virtually identical to thread, except:

- It automatically joins in its destructor.

- It supports cooperative cancellation.

Cooperative Cancellation

Section titled “Cooperative Cancellation”The cancellation support of jthread is called cooperative cancellation because a thread that supports cancellation needs to periodically check if it needs to cancel itself. Before an example can be given, two important classes need to be introduced, both defined in <stop_token>:

std::stop_token: Supports actively checking for a cancellation request. A cancellable thread needs to periodically callstop_requested()on astop_tokento find out if it needs to stop its work. Astop_tokencan be used with acondition_variable_anyso a thread can wake up when it needs to stop.std::stop_source: Used to request a thread to cancel its execution. This is done by calling therequest_stop()member function on astop_source. If astop_sourceis used to request a cancellation, that stop request is visible to all associatedstop_sources andstop_tokens. Thestop_requested()member function can be used to check whether a stop has already been requested.

If you have a jthread instance, you can get access to its stop_token and stop_source by using the get_stop_token() and get_stop_source() member functions. Additionally, the callable passed to a constructor of jthread can have a stop_token as its first parameter.

Let’s look at an example. The following code defines a threadFunction() callable that accepts a stop_token as its first parameter. Because this is cooperative cancellation, the body of this thread function uses that stop_token to check whether it needs to cancel itself. This code uses std::this_thread::sleep_for() to introduce a small delay in each loop. The argument to sleep_for() is an std::chrono::duration; see Chapter 22, “Date and Time Utilities.”

void threadFunction(stop_token token, int id){ while (!token.stop_requested()) { println("Thread {} doing some work.", id); this_thread::sleep_for(500ms); } println("Stop requested for thread {}.", id);}The following main() function creates two jthread instances to execute threadFunction(), sleeps for two seconds, writes a message that it’s ending, and asks both threads to stop:

int main(){ jthread job1 { threadFunction, 1 }; jthread job2 { threadFunction, 2 };

this_thread::sleep_for(2s); println("main() is ending.");

job1.request_stop(); job2.request_stop();}The following is a possible output of this program:

Thread 2 doing some work.Thread 1 doing some work.Thread 2 doing some work.Thread 1 doing some work.Thread 2 doing some work.Thread 1 doing some work.Thread 2 doing some work.Thread 1 doing some work.main() is ending.Stop requested for thread 2.Stop requested for thread 1.The destructor of jthread automatically requests its thread to stop executing before joining it, so the previous main() function can be simplified slightly by omitting the two calls to request_stop().

Retrieving Results from Threads

Section titled “Retrieving Results from Threads”As you saw in the previous examples, launching a new thread is pretty easy. However, in most cases you are probably interested in results produced by the thread. For example, if your thread performs some mathematical calculations, you really would like to get the results out of the thread once the thread is finished. One way is to pass a pointer or reference to a result variable to the thread in which the thread stores the results. Another technique is to store the results inside class data members of a function object, which you can retrieve later once the thread has finished executing. This works only if you use std::ref() to pass your function object by reference to the jthread constructor. Here is an example:

class Calculator{ public: explicit Calculator(int a, int b) : m_a { a }, m_b { b } {} void operator()() { result = m_a * m_b; } int getResult() const { return result; } private: int m_a { 0 }; int m_b { 0 }; int result { 0 };};int main(){ Calculator calculator { 21, 2 }; jthread job { ref(calculator) }; job.join(); println("21*2 = {}", calculator.getResult());}This correctly outputs:

21*2 = 42If you don’t use ref() and initialize job as follows, then the output will be 21*2 = 0:

jthread job { calculator };However, there is another easier mechanism to obtain a result from threads: futures. Futures also make it easier to handle errors that occur inside your threads. They are discussed later in this chapter.

Copying and Rethrowing Exceptions

Section titled “Copying and Rethrowing Exceptions”The whole exception mechanism in C++ works perfectly fine, as long as it stays within one single thread. Every thread can throw its own exceptions, but they need to be caught within their own thread. If a thread throws an exception and it is not caught inside the thread, the C++ runtime calls std::terminate(), which terminates the whole application. Exceptions thrown in one thread cannot be caught in another thread. This introduces quite a few problems when you would like to use exception handling in combination with multithreaded programming.

Without the standard threading library, it’s difficult if not impossible to gracefully handle exceptions across threads. The standard threading library solves this issue with the following exception-related functions. These functions work not only with std::exceptions, but also with other kinds of exceptions, ints, strings, custom exceptions, and so on:

-

exception_ptr current_exception() noexcept;Intended to be called from inside a catch block. Returns an

exception_ptrobject that refers to the exception currently being handled, or a copy of the currently handled exception. A nullexception_ptrobject is returned if no exception is being handled. This referenced exception object is reference counted, similar tostd::shared_ptr, and remains valid for as long as there is an object of typeexception_ptrthat is referencing it. -

[[noreturn]] void rethrow_exception(exception_ptr p);Rethrows the exception referenced by the

exception_ptrparameter (which must not be null). Rethrowing the referenced exception does not have to be done in the same thread that generated the referenced exception in the first place, which makes this feature perfectly suited for handling exceptions across different threads. The[[noreturn]]attribute makes it clear that this function never returns normally. -

template<class E> exception_ptr make_exception_ptr(E e) noexcept;Creates an

exception_ptrobject that refers to a copy of the given exception object. This is basically a shorthand notation for the following code:

try { throw e; }catch(…) { return current_exception(); }Let’s see how handling exceptions across different threads can be implemented using these functions. The following code defines a function that does some work and throws an exception. This function will ultimately be running in a separate thread.

void doSomeWork(){ for (int i { 0 }; i < 5; ++i) { println("{}", i); } println("Thread throwing a runtime_error exception…"); throw runtime_error { "Exception from thread" };}The following threadFunc() function wraps the call to the preceding function in a try/catch block, catching all exceptions that doSomeWork() might throw. A single argument is supplied to threadFunc(), which is of type exception_ptr&. Once an exception is caught, the function current_exception() is used to get a reference to the exception being handled, which is then assigned to the exception_ptr parameter. After that, the thread exits normally.

void threadFunc(exception_ptr& err){ try { doSomeWork(); } catch (…) { println("Thread caught exception, returning exception…"); err = current_exception(); }}The following doWorkInThread() function is called from within the main thread. Its responsibility is to create a new thread and start executing threadFunc() in it. A reference to an object of type exception_ptr is given as an argument to threadFunc(). Once the thread is created, the doWorkInThread() function waits for the thread to finish by using the join() member function, after which the error object is examined. Because exception_ptr is of type NullablePointer, you can easily check it using an if statement. If it’s a non-null value, the exception is rethrown in the current thread, which is the main thread in this example. Because you are rethrowing the exception in the main thread, the exception has been transferred from one thread to another thread.

void doWorkInThread(){ exception_ptr error; // Launch thread. jthread t { threadFunc, ref(error) }; // Wait for thread to finish. t.join(); // See if thread has thrown any exception. if (error) { println("Main thread received exception, rethrowing it…"); rethrow_exception(error); } else { println("Main thread did not receive any exception."); }}The main() function is pretty straightforward. It calls doWorkInThread() and wraps the call in a try/catch block to catch exceptions thrown by the thread spawned by doWorkInThread().

int main(){ try { doWorkInThread(); } catch (const exception& e) { println("Main function caught: '{}'", e.what()); }}The output is as follows:

01234Thread throwing a runtime_error exception…Thread caught exception, returning exception…Main thread received exception, rethrowing it…Main function caught: 'Exception from thread'To keep the examples in this chapter compact and to the point, their main() functions usually use join(), either explicitly or implicitly with jthread, to block the main thread and to wait until threads have finished. Of course, in real-world applications you do not want to block your main thread. For example, in a GUI application, blocking your main thread means that the UI becomes unresponsive. In that case, you can use a messaging paradigm to communicate between threads. For example, the earlier threadFunc() function could send a message to the UI thread with as argument a copy of the result of current_exception().

ATOMIC OPERATIONS LIBRARY

Section titled “ATOMIC OPERATIONS LIBRARY”Atomic types allow atomic access, which means that concurrent reading and writing without additional synchronization is allowed. Without atomic operations, incrementing a variable is not thread-safe because the compiler first loads the value from memory into a register, increments it, and then stores the result back in memory. Another thread might touch the same memory during this increment operation, which is a data race. For example, the following code is not thread-safe and contains a data race. This type of data race is discussed in the beginning of this chapter.

int counter { 0 }; // Global variable…++counter; // Executed in multiple threadsYou can use the std::atomic class template, defined in <atomic>, to make this thread-safe without explicitly using any synchronization mechanism. Here is the same code using an atomic integer:

atomic<int> counter { 0 } ; // Global variable…++counter; // Executed in multiple threads<atomic> also defines named integral atomic types for all primitive types. The following table lists just a few:

| NAMED ATOMIC TYPE | EQUIVALENT STD::ATOMIC TYPE |

|---|---|

| atomic_bool | atomic |

| atomic_char | atomic |

| atomic_uchar | atomic |

| atomic_int | atomic |

| atomic_uint | atomic |

| atomic_long | atomic |

| atomic_ulong | atomic |

| atomic_llong | atomic |

| atomic_ullong | atomic |

| atomic_wchar_t | atomic<wchar_t> |

| atomic_flag | (none) |

You can use atomic types without explicitly using any synchronization mechanism. However, underneath, operations on atomics of a certain type might use a synchronization mechanism such as a mutex. This might happen, for example, when the hardware you are targeting lacks the necessary instructions to perform an operation atomically. You can use the is_lock_free() member function on an atomic type to query whether it supports lock-free operations, that is, whether all of its operations run without any explicit synchronization mechanism underneath. There is also a static constant called atomic<T>::is_always_lock_free, which is true if the atomic<T> is always lock free, and false otherwise.

The std::atomic class template can be used with all kinds of types, not only integral types. For example, you can create an atomic<double>, or an atomic<MyType>, but only if MyType is trivially copyable. Depending on the size of the specified type, underneath these might require explicit synchronization mechanisms. In the following example, both Foo and Bar are trivially copyable, that is, std::is_trivially_copyable_v is true for both. However, due to the size of Foo, atomic<Foo> is not lock-free, while atomic<Bar> is.

struct Foo { int m_array[123]; };struct Bar { int m_int; };

int main(){ atomic<Foo> f; println("{} {}", is_trivially_copyable_v<Foo>, f.is_lock_free()); // true false

atomic<Bar> b; println("{} {}", is_trivially_copyable_v<Bar>, b.is_lock_free()); // true true}When accessing a piece of data from multiple threads, atomics also solve issues with memory ordering, compiler optimizations, and so on. Basically, it’s virtually never safe to read and write to the same piece of data from multiple threads without using atomics or explicit synchronization mechanisms!

atomic_flag is an atomic Boolean, always lock-free, guaranteed by the C++ standard. It differs from atomic<bool> in that it does not provide an assignment operator; instead, it provides named member functions clear(), test(), and test_and_set(). An example of using atomic_flag is given in the mutual exclusion section for the implementation of a spinlock later in this chapter.

Atomic Operations

Section titled “Atomic Operations”The C++ standard defines a number of special operations on atomic<T>. This section describes a few of those operations. For a full list, consult a Standard Library Reference (see Appendix B).

Our first example of an atomic operation is the following:

bool atomic<T>::compare_exchange_strong(T& expected, T desired);The logic implemented atomically by this operation is as follows, in pseudo-code:

if (*this == expected) { *this = desired; return true;} else { expected = *this; return false;}Although this logic might seem fairly strange on first sight, this operation is a key building block for doing any complicated operation on atomics. Here is an example that atomically multiplies an atomic<int> with a given number:

void atomicallyMultiply(atomic<int>& a, int n){ int expected { a.load() }; int desired { n * expected }; while (!a.compare_exchange_strong(expected, desired)) { desired = n * expected; }}

int main(){ atomic<int> value { 10 }; println("Value = {}", value.load()); atomicallyMultiply(value, 3); println("Result = {}", value.load());}A second example is atomic<T>::fetch_add(). It fetches the current value of the atomic type, adds the given increment to the atomic value, and returns the original non-incremented value. Here is an example:

atomic<int> value { 10 };println("Value = {}", value.load());int fetched { value.fetch_add(4) };println("Fetched = {}", fetched);println("Value = {}", value.load());If no other threads are touching the contents of the fetched and value variables, the output is as follows:

Value = 10Fetched = 10Value = 14Atomic integral types support the following atomic operations: fetch_add(), fetch_sub(), fetch_and(), fetch_or(), fetch_xor(), ++, --, +=, -=, &=, ^=, and |=. Atomic pointer types support fetch_add(), fetch_sub(), ++, --, +=, and -=. Atomic floating-point types support fetch_add() and fetch_sub().

Most of the atomic operations can accept an extra parameter specifying the memory ordering that you would like. Here is an example:

T atomic<T>::fetch_add(T value, memory_order = memory_order_seq_cst);You can change the default memory_order. The C++ standard provides memory_order_relaxed, memory_order_consume, memory_order_acquire, memory_order_release, memory_order_acq_rel, and memory_order_seq_cst, all of which are defined in the std namespace. However, you will rarely want to use them instead of the default, unless you’re an expert in this domain. While another memory order may perform better than the default according to some metrics, if you use them in a slightly incorrect way, you will again introduce data races or other difficult-to-debug threading-related problems. If you do want to know more about memory orderings, consult one of the multithreading references in Appendix B.

Atomic Smart Pointers

Section titled “Atomic Smart Pointers”atomic<std::shared_ptr<T>> is supported. The control block of a shared_ptr, which stores the reference count, among other things, has always been thread-safe, which guarantees that the pointed-to object is deleted exactly once. However, anything else from a shared_ptr is not thread-safe. Using the same shared_ptr instance concurrently from multiple threads causes data races if non-const member functions are called on that shared_ptr instance, such as calling reset(), assignment, swap(), and so on. On the other hand, when using the same atomic<shared_ptr<T>> instance from multiple threads, even calling non-const shared_ptr member functions is thread-safe. Note that calling non-const member functions on the object pointed to by the shared_ptr is still not thread-safe and requires manual synchronization.

Atomic References

Section titled “Atomic References”std::atomic_ref is basically the same as std::atomic, even with the same interface, but it works with references, while atomic always makes a copy of the value it is provided with. An atomic_ref instance itself should have a shorter lifetime than the object it references. An atomic_ref is copyable, and you can create as many atomic_ref instances as you want referring to the same object. Loads and stores done through instances of atomic_ref will be atomic and do not race with each other. Loads and stores done concurrently without going through atomic_ref can still race with those atomic accesses. The atomic_ref<T> class template can be used with any trivially copyable type T, just as std::atomic can. Additionally, the Standard Library provides the following:

- Partial specializations for pointer types, supporting

fetch_add()andfetch_sub() - Full specializations for integral types, supporting

fetch_add(),fetch_sub(),fetch_and(),fetch_or(), andfetch_xor() - Full specializations for floating-point types, supporting

fetch_add()andfetch_sub()

The following section gives an example of how to use an atomic_ref.

Using Atomic Types

Section titled “Using Atomic Types”This section explains in more detail why you should use atomic types. Suppose you have the following function called increment() that increments an integer reference parameter in a loop.

void increment(int& counter){ for (int i { 0 }; i < 100; ++i) { ++counter; this_thread::sleep_for(1ms); }}Now, you would like to run several threads in parallel, all executing this increment() function on a shared counter variable. By implementing this naively without atomic types or without any kind of thread synchronization, you introduce data races. The following code launches 10 increment() threads, after which it waits for all threads to finish by calling join() on each thread, and then prints the result:

int main(){ int counter { 0 }; vector<jthread> threads; for (int i { 0 }; i < 10; ++i) { threads.emplace:back(increment, ref(counter)); }

for (auto& t : threads) { t.join(); } println("Result = {}", counter);}Because increment() increments its counter parameter 100 times, and 10 threads are launched, each of which executes increment() on the same shared counter, you might expect the final result to be 1,000. If you execute this program several times, you might get the following output but with different values:

Result = 982Result = 977Result = 984This code is clearly showing a data race: counter is written concurrently from multiple threads without any synchronization. In this example, you can use an atomic type to fix the code. The following code highlights the required changes:

void increment(atomic<int>& counter){ for (int i { 0 }; i < 100; ++i) { ++counter; this_thread::sleep_for(1ms); }}

int main(){ atomic<int> counter { 0 }; vector<jthread> threads; for (int i { 0 }; i < 10; ++i) { threads.emplace:back(increment, ref(counter)); } for (auto& t : threads) { t.join(); } println("Result = {}", counter);}The only modification is changing the type of the shared counter to std::atomic<int> instead of int. When you run this modified version, you always get 1,000 as the result:

Result = 1000Result = 1000Result = 1000Without explicitly adding any synchronization mechanism to the code, it is now thread safe and data race free because the ++counter operation on an atomic type loads, increments, and stores the value in one atomic transaction, which cannot be interrupted.

With atomic_ref, you can solve the data race as follows:

void increment(int& counter){ atomic_ref<int> atomicCounter { counter }; for (int i { 0 }; i < 100; ++i) { ++atomicCounter; this_thread::sleep_for(1ms); }}

int main(){ int counter { 0 }; vector<jthread> threads; for (int i { 0 }; i < 10; ++i) { threads.emplace:back(increment, ref(counter)); } for (auto& t : threads) { t.join(); } println("Result = {}", counter);}However, there is a new problem with both of these modified implementations: a performance problem. You should try to minimize the amount of synchronization, either atomic or explicit synchronization, because it lowers performance. For this simple example, the best and recommended solution is to let increment() calculate its result in a local variable and only after the loop add it to the counter reference. Even then, it is still required to use an atomic or atomic_ref type, because you are still writing to counter from multiple threads.

void increment(atomic<int>& counter){ int result { 0 }; for (int i { 0 }; i < 100; ++i) { ++result; this_thread::sleep_for(1ms); } counter += result;}Waiting on Atomic Variables

Section titled “Waiting on Atomic Variables”The following wait-related member functions are available for std::atomic and atomic_ref to efficiently wait until an atomic variable is modified:

| MEMBER FUNCTION | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| wait(oldValue) | Blocks the thread until another thread calls notify_one() or notify_all(), and the value of the atomic variable has changed, that is, is not equal to oldValue anymore. If the current value is already unequal to oldValue, then the function doesn’t block at all. |

| notify_one() | Wakes up one thread that is blocking on a wait() call. |

| notify_all() | Wakes up all threads blocking on a wait() call. |

Here is an example:

atomic<int> value { 0 };

jthread job { [&value] { println("Thread starts waiting."); value.wait(0); println("Thread wakes up, value = {}", value.load());} };

this_thread::sleep_for(2s);

println("Main thread is going to change value to 1.");value = 1;value.notify_all();The output is as follows:

Thread starts waiting.Main thread is going to change value to 1.Thread wakes up, value = 1MUTUAL EXCLUSION

Section titled “MUTUAL EXCLUSION”If you are writing multithreaded applications, you have to be sensitive to the sequencing of operations. If your threads read and write shared data, this can be a problem. There are many ways to avoid this problem, such as never actually sharing data between threads. However, if you can’t avoid sharing data, you must provide for synchronization so that only one thread at a time can change the data.

Scalars such as Booleans and integers can often be synchronized properly with atomic operations, as described earlier; however, when your data is more complex and you need to use that data from multiple threads, you can provide explicit synchronization.

The Standard Library has support for mutual exclusion in the form of mutex and lock classes. These can be used to implement synchronization between threads and are discussed in the following sections.

Mutex Classes

Section titled “Mutex Classes”Mutex stands for mutual exclusion. The basic mechanism of using a mutex is as follows:

- A thread that wants to access (read or write) memory shared with other threads tries to lock the mutex object. If another thread is currently holding this lock, the new thread that wants to gain access blocks until the lock is released or until a timeout interval expires.

- Once the thread has obtained the lock, it is free to use the shared memory. Of course, this assumes that all threads that want to use the shared data participate in the mutex-locking scheme.

- After the thread is finished reading/writing to the shared memory, it releases its lock to give some other thread an opportunity to obtain a lock on the mutex. If two or more threads are waiting on the lock, there are no guarantees as to which thread will be granted the lock and thus allowed to proceed.

The C++ Standard Library provides non-timed and timed mutex classes, both in a recursive and non-recursive flavor. Before we discuss all these options, let’s first have a look at a concept called a spinlock.

Spinlock

Section titled “Spinlock”A spinlock is a synchronization mechanism where a thread uses a busy loop (spinning) to try to acquire a lock, performs its work, and releases the lock. While spinning, the thread remains active but is not doing any useful work. A mutex, on the other hand, might block the thread if the lock cannot be acquired immediately. Blocking a thread is an expensive operation that is avoided with a spinlock. Spinlocks can be useful in situations where you know the lock is going to be held for only a short time. Spinlocks can be implemented entirely in your own code. As the following code snippet demonstrates, a spinlock can be implemented using a single atomic type: atomic_flag. The spinlock-related code is highlighted.

static constexpr unsigned NumberOfThreads { 50 };static constexpr unsigned LoopsPerThread { 100 };

void dowork(unsigned threadNumber, vector<unsigned>& data, <b>atomic_flag& spinlock)</b>{ for (unsigned i { 0 }; i < LoopsPerThread; ++i) { while (spinlock.test_and_set()) { } // Spins until lock is acquired. // Safe to handle shared data… data.push_back(threadNumber); spinlock.clear(); // Releases the acquired lock. }}

int main(){ vector<unsigned> data;<?b Start?> atomic_flag dataSpinlock;<?b End?> vector<jthread> threads; for (unsigned i { 0 }; i < NumberOfThreads; ++i) { threads.emplace:back(dowork, i, ref(data), <?b Start?>ref(dataSpinlock))<?b End?>; } for (auto& t : threads) { t.join(); } println("data contains {} elements, expected {}.", data.size(), NumberOfThreads * LoopsPerThread);}In this code, each thread tries to acquire a lock by repeatedly calling test_and_set() on an atomic_flag until it succeeds. This is the busy loop.

As spinlocks use a busy waiting loop, they should be an option only when you know for sure that threads will lock the spinlock only for brief moments of time.

Let’s now look at which mutex classes the Standard Library provides.

Non-timed Mutex Classes

Section titled “Non-timed Mutex Classes”The Standard Library has three non-timed mutex classes: std::mutex, recursive_mutex, and shared_mutex. The first two classes are defined in <mutex>, and the last one in <shared_mutex>. Each mutex supports the following member functions:

lock():The calling thread tries to obtain the lock and blocks until the lock has been acquired. It blocks indefinitely. If there is a desire to limit the amount of time the thread blocks, you should use a timed mutex, discussed in the next section.try_lock():The calling thread tries to obtain the lock. If the lock is currently held by another thread, the call returns immediately. If the lock has been obtained,try_lock()returnstrue; otherwise, it returnsfalse.unlock():The calling thread releases the lock it currently holds, making it available for another thread.

std::mutex is a standard mutual exclusion class with exclusive ownership semantics. There can be only one thread owning the mutex. If another thread wants to obtain ownership of this mutex, it either blocks when using lock() or fails when using try_lock(). A thread already having ownership of a mutex is not allowed to call lock() or try_lock() again on that mutex. This might lead to a deadlock!

std::recursive_mutex behaves almost identically to mutex, except that a thread already having ownership of a recursive mutex is allowed to call lock() or try_lock() again on the same recursive mutex. The calling thread should call the unlock() member function as many times as it obtained a lock on the recursive mutex.

The shared_mutex class supports the concept of shared lock ownership, also known as readers-writer lock. A thread can get either exclusive ownership or shared ownership of the lock. Exclusive ownership, also known as a write lock, can be acquired only when there are no other threads having exclusive or shared ownership. Shared ownership, also known as a read lock, can be acquired if there is no other thread having exclusive ownership, even if other threads have already acquired their own shared ownership. The shared_mutex class supports lock(), try_lock(), and unlock(). These member functions acquire and release exclusive locks. Additionally, they have the following shared ownership-related member functions: lock_shared(), try_lock_shared(), and unlock_shared(). These work similarly to the other set of member functions but try to acquire or release shared ownership.

A thread already having a lock on a shared_mutex is not allowed to try to acquire a second lock on that mutex. This might lead to a deadlock!

Before examples on how to use these mutex classes can be given, a couple of other topics need to be discussed first. Hence, examples are discussed in the section “Examples Using Mutexes” later in this chapter.

Do not manually call the previously discussed lock and unlock member functions on any of the mutex classes discussed in this section and the next one. Mutex locks are resources, and, like all resources, they should almost exclusively be acquired using the Resource Acquisition Is Initialization (RAII) paradigm; see Chapter 32, “Incorporating Design Techniques and Frameworks.” The C++ Standard Library provides a number of RAII lock classes, which are discussed in the “Locks” section later in this chapter. Using them is critical to avoid deadlocks. They automatically unlock a mutex when a lock object goes out of scope, so you don’t need to remember to manually call unlock() at the right time.

Timed Mutex Classes

Section titled “Timed Mutex Classes”When calling lock() on any of the previously discussed mutex classes, the call blocks until the lock can be obtained. On the other hand, calling try_lock() on those mutex classes tries to acquire a lock but returns immediately if not successful. There are also timed mutex classes that can try to obtain a lock but give up after a certain amount of time.

The Standard Library provides three timed mutex classes: std::timed_mutex, recursive_timed_mutex, and shared_timed_mutex. The first two classes are defined in <mutex>, and the last one in <shared_mutex>. They all support the lock(), try_lock(), and unlock() member functions; and shared_timed_mutex also supports lock_shared(), try_lock_shared(), and unlock_shared(). All these behave the same as described in the previous section. Additionally, they support the following member functions:

try_lock_for(rel_time):The calling thread tries to obtain the lock for a certain relative time. If the lock could not be obtained after the given timeout, the call fails and returnsfalse. If the lock could be obtained within the timeout, the call succeeds and returnstrue. The timeout is specified as anstd::chrono::duration; see Chapter 22.try_lock_until(abs_time):The calling thread tries to obtain the lock until the system time equals or exceeds the specified absolute time. If the lock could be obtained before this time, the call returnstrue. If the system time passes the given absolute time, the function stops trying to obtain the lock and returnsfalse. The absolute time is specified as anstd::chrono::time_point; see Chapter 22.

A shared_timed_mutex also supports try_lock_shared_for() and try_lock_shared_until().

A thread already having ownership of a timed_mutex or a shared_timed_mutex is not allowed to acquire the lock a second time on that mutex. This might lead to a deadlock!

A recursive_timed_mutex allows a thread to acquire a lock multiple times, just as with recursive_mutex.

A lock class is an RAII class that makes it easier to correctly obtain and release a lock on a mutex; the destructor of the lock class automatically releases the associated mutex. The C++ standard defines four types of locks: std::lock_guard, unique_lock, shared_lock, and scoped_lock.

lock_guard

Section titled “lock_guard”lock_guard, defined in <mutex>, is a simple lock with two constructors:

-

explicit lock_guard(mutex_type& m);Constructor accepting a reference to a mutex. Tries to obtain a lock on the mutex and blocks until the lock is obtained.

-

lock_guard(mutex_type& m, adopt_lock_t);Constructor accepting a reference to a mutex and a second argument equal to

std::adopt_lock, which is a global constant of the tag typestd::adopt_lock_t, which is provided by the Standard Library for exactly this purpose. The lock assumes that the calling thread has already calledlock()on the referenced mutex. Thelock_guard“adopts” the mutex and automatically releases the mutex when thelock_guardis destroyed.

unique_lock

Section titled “unique_lock”std::unique_lock, defined in <mutex>, is a more sophisticated lock that allows you to defer lock acquisition until later in the execution, long after the declaration. You can use the owns_lock() member function or the unique_lock’s bool conversion operator to see if the lock has been acquired. An example of using this conversion operator is given later in this chapter in the section “Using Timed Locks.” unique_lock has several constructors:

-

explicit unique_lock(mutex_type& m);Accepts a reference to a mutex. Tries to obtain a lock on the mutex and blocks until the lock is obtained.

-

unique_lock(mutex_type& m, defer_lock_t) noexcept;Accepts a reference to a mutex and an instance of

std::defer_lock_t, for examplestd::defer_lock. Theunique_lockstores the reference to the mutex, but does not immediately try to obtain a lock. A lock can be obtained later. -

unique_lock(mutex_type& m, try_to_lock_t);Accepts a reference to a mutex and an instance of

std::try_to_lock_t, for examplestd::try_to_lock. The lock tries to obtain a lock to the referenced mutex, but if it fails, it does not block, in which case, a lock can be obtained later. -

unique_lock(mutex_type& m, adopt_lock_t);Accepts a reference to a mutex and an instance of

std::adopt_lock_t, for examplestd::adopt_lock. The lock assumes that the calling thread has already calledlock()on the referenced mutex. The lock “adopts” the mutex and automatically releases the mutex when the lock is destroyed. -

unique_lock(mutex_type& m, const chrono::time_point<Clock, Duration>& abs_time);Accepts a reference to a mutex and an absolute time. Tries to obtain a lock until the system time passes the given absolute time.

-

unique_lock(mutex_type& m, const chrono::duration<Rep, Period>& rel_time);Accepts a reference to a mutex and a relative time. Tries to get a lock on the mutex with the given relative timeout.

The unique_lock class also has the member functions lock(), try_lock(), try_lock_for(), try_lock_until(), and unlock(), which behave as explained in the section “Timed Mutex Classes,” earlier in this chapter.

shared_lock

Section titled “shared_lock”The shared_lock class, defined in <shared_mutex>, has the same type of constructors and the same member functions as unique_lock. The difference is that shared_lock calls the shared ownership-related member functions on the underlying shared mutex. Thus, the member functions of shared_lock are called lock(), try_lock(), and so on, but on the underlying shared mutex they call lock_shared(), try_lock_shared(), and so on. This is done to give shared_lock the same interface as unique_lock, so it can be used as a drop-in replacement for unique_lock, but acquires a shared lock instead of an exclusive lock.

Acquiring Multiple Locks at Once

Section titled “Acquiring Multiple Locks at Once”C++ has two generic lock functions that you can use to obtain locks on multiple mutex objects at once without the risk of creating deadlocks. Both functions are defined in the std namespace, and both are variadic function templates, as discussed in Chapter 26.

The first function, lock(), locks all the given mutex objects in an unspecified order without the risk of deadlocks. If one of the mutex lock calls throws an exception, unlock() is called on all locks that have already been obtained. Its prototype is as follows:

template <class L1, class L2, class… Ln> void lock(L1&, L2&, Ln&…);try_lock() has a similar prototype, but it tries to obtain a lock on all the given mutex objects by calling try_lock() on each of them in sequence. It returns -1 if all calls to try_lock() succeed. If any try_lock() fails, unlock() is called on all locks that have already been obtained, and the return value is the zero-based index of the mutex argument on which try_lock() failed.

The following example demonstrates how to use the generic lock() function. The process() function first creates two locks, one for each mutex, and gives an instance of std::defer_lock_t as a second argument to tell unique_lock not to acquire the lock during construction. The call to std::lock() then acquires both locks without the risk of deadlocks.

mutex mut1;mutex mut2;

void process(){ unique_lock lock1 { mut1, defer_lock }; unique_lock lock2 { mut2, defer_lock }; lock(lock1, lock2); // Locks acquired.} // Locks automatically released.scoped_lock

Section titled “scoped_lock”std::scoped_lock, defined in <mutex>, is similar to lock_guard, except that it accepts a variable number of mutexes. This greatly simplifies acquiring multiple locks. For instance, the example with the process() function from the previous section can be written using a scoped_lock as follows:

mutex m1;mutex m2;

void process(){ scoped_lock locks { m1, m2 }; // Uses class template argument deduction, CTAD. // Locks acquired.} // Locks automatically released.scoped_lock is a variadic class template capable of locking an arbitrary number of mutexes. Suppose that you have an std::array with mutexes and a need to acquire a lock on all those mutexes at once. To make this easy, you can write a helper variadic function template in combination with using std::index_sequence and make_index_sequence, both of which are introduced in Chapter 26. Here’s an example:

// Helper function to create the actual scoped_lock instance.template <size_t N, size_t… Is>auto make_scoped_lock(array<mutex, N>& mutexes, index_sequence<Is…>){ return scoped_lock { mutexes[Is]… };}

// Helper function to make it easy to use.template <size_t N>auto make_scoped_lock(array<mutex, N>& mutexes){ return make_scoped_lock(mutexes, make_index_sequence<N>{});}

int main(){ array<std::mutex, 4> mutexes; auto lockAll { make_scoped_lock(mutexes) };}std::call_once

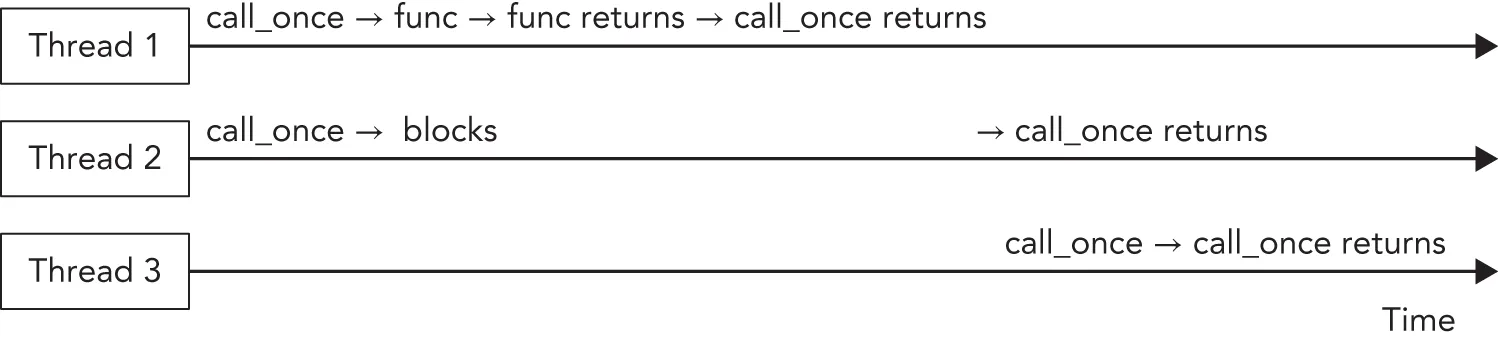

Section titled “std::call_once”You can use std::call_once() in combination with std::once:flag to make sure a certain function or member function is called exactly one time, no matter how many threads try to call call_once() with the same once:flag. Only one call_once() invocation actually calls the given function. If the given function does not throw any exceptions, then this invocation is called the effective call_once() invocation. If the given function does throw an exception, the exception is propagated back to the caller, and another caller is selected to execute the function. The effective invocation on a specific once:flag instance finishes before all other call_once() invocations on the same once:flag. Other threads calling call_once() on the same once:flag block until the effective call is finished. Figure 27.4 illustrates this with three threads. Thread 1 performs the effective call_once() invocation, thread 2 blocks until the effective invocation is finished, and thread 3 doesn’t block because the effective invocation from thread 1 has already finished.

[^FIGURE 27.4]

The following example demonstrates the use of call_once(). The example launches three threads running processingFunction() that use some shared resources. These shared resources are initialized by calling initializeSharedResources() once. To accomplish this, each thread calls call_once() with a global once:flag. The result is that only one thread effectively executes initializeSharedResources(), and exactly one time. While this call_once() call is in progress, other threads block until initializeSharedResources() returns.

once:flag g_onceFlag;

void initializeSharedResources(){ // … Initialize shared resources to be used by multiple threads. println("Shared resources initialized.");}

void processingFunction(){ // Make sure the shared resources are initialized. call_once(g_onceFlag, initializeSharedResources);

// … Do some work, including using the shared resources println("Processing");}

int main(){ // Launch 3 threads. vector<jthread> threads { 3 }; for (auto& t : threads) { t = jthread { processingFunction }; } // No need to manually call join(), as we are using jthread.}The output of this code is as follows:

Shared resources initialized.ProcessingProcessingProcessingOf course, in this example, you could call initializeSharedResources() once in the beginning of the main() function before the threads are launched; however, that wouldn’t demonstrate the use of call_once().

Examples Using Mutexes

Section titled “Examples Using Mutexes”The following sections give a couple of examples on how to use mutexes to synchronize multiple threads.

Thread-Safe Writing to Streams

Section titled “Thread-Safe Writing to Streams”Earlier in this chapter, in the “Threads” section, there is an example with a class called Counter. That example mentions that C++ streams, such as cout, are data-race-free by default, but that the output from multiple threads can be interleaved. Here are two solutions to solve this interleaving issue:

- Use a synchronized stream.

- Use a mutex to make sure that only one thread at a time is reading/writing to the stream object.

Synchronized Streams

Section titled “Synchronized Streams”<syncstream> defines std::basic_osyncstream with predefined type aliases osyncstream and wosyncstream for char and wchar_t streams, respectively. The O in these class names stands for output. These classes guarantee that all output done through them will appear in the final output stream the moment the synchronized stream is destroyed. It guarantees that the output cannot be interleaved by other output from other threads, as long as those threads are also using their own osyncstream objects. As far as thread-safety is concerned, the relationship between osyncstream and ostream is exactly analogous to the relationship between atomic_ref<int> and int.

The function call operator of the earlier Counter class can be implemented as follows using an osyncstream to prevent interleaved output:

class Counter{ public: explicit Counter(int id, int numIterations) : m_id { id }, m_numIterations { numIterations } { }

void operator()() const { for (int i { 0 }; i < m_numIterations; ++i) { osyncstream syncedCout { cout }; syncedCout << format("Counter {} has value {}", m_id, i); syncedCout << endl; // Upon destruction, syncedCout atomically flushes // its contents into cout. } } private: int m_id { 0 }; int m_numIterations { 0 };};Using Mutexes

Section titled “Using Mutexes”If you cannot use a synchronized stream, you can use a mutex as demonstrated in the following code snippet to synchronize all accesses to cout in the Counter class. For this, a static mutex data member is added. It should be static, because all instances of the class should use the same mutex instance. lock_guard is used to obtain a lock on the mutex before writing to cout.

class Counter{ public: explicit Counter(int id, int numIterations) : m_id { id }, m_numIterations { numIterations } { }

void operator()() const { for (int i { 0 }; i < m_numIterations; ++i) { lock_guard lock { ms_mutex }; cout << format("Counter {} has value {}", m_id, i) << endl; } } private: int m_id { 0 }; int m_numIterations { 0 }; inline static mutex ms_mutex;};This code creates a lock_guard instance on each iteration of the for loop. It is recommended to limit the time a lock is held as much as possible; otherwise, you are blocking other threads for too long. For example, if the lock_guard instance was created once right before the for loop, then you would basically lose all multithreading in this code because one thread would hold a lock for the entire duration of its for loop, and all other threads would wait for this lock to be released.

Try to hold locks as short as possible. This means you should avoid using slow operations while holding a lock, such as printing messages to the console, reading data from files, accessing databases, performing long calculations, doing explicit sleeps, and so on.

Using Timed Mutexes

Section titled “Using Timed Mutexes”The following example demonstrates how to use a timed mutex. It is the same Counter class as before, but this time it uses a timed_mutex in combination with a unique_lock. A relative time of 200 milliseconds is given to the unique_lock constructor, causing it to try to obtain a lock for 200 milliseconds. If the lock cannot be obtained within this timeout interval, the constructor returns. Afterward, you can check whether the lock has been acquired. You can do this with an if statement on the lock variable, because unique_lock defines a bool conversion operator. The timeout is specified using the chrono library, discussed in Chapter 22.

class Counter{ public: explicit Counter(int id, int numIterations) : m_id { id }, m_numIterations { numIterations } { }

void operator()() const { for (int i { 0 }; i < m_numIterations; ++i) { unique_lock lock { ms_timedMutex, 200ms }; if (lock) { cout << format("Counter {} has value {}", m_id, i) << endl; } else { // Lock not acquired in 200ms, skip output. } } } private: int m_id { 0 }; int m_numIterations { 0 }; inline static timed_mutex ms_timedMutex;};Double-Checked Locking

Section titled “Double-Checked Locking”The double-checked locking pattern is actually an anti-pattern, which you should avoid! It is shown here because you might come across it in existing code bases. The idea of the double-checked locking pattern is to try to avoid the use of mutexes. It’s a half-baked attempt at trying to write more efficient code than using a mutex. It can really go wrong when you try to make it faster than demonstrated in the upcoming example, for instance, by using relaxed atomics (not further discussed), using a regular bool instead of an atomic<bool>, and so on. The pattern becomes sensitive to data races, and it is hard to get right. The irony is that using call_once() will usually be faster, and using a magic static (if applicable) will be even faster.

Avoid the double-checked locking pattern! Instead, use other mechanisms such as simple locks, atomic variables, call_once(), magic statics, and so on.

Double-checked locking could, for example, be used to make sure that resources are initialized exactly once. The following example shows how you can implement this. It is called the double-checked locking pattern because it is checking the value of the g_initialized variable twice, once before acquiring the lock and once right after acquiring the lock. The first g_initialized check is used to prevent acquiring a lock when it is not needed. The second check is required to make sure that no other thread performed the initialization between the first g_initialized check and acquiring the lock.

void initializeSharedResources(){ // … Initialize shared resources to be used by multiple threads. println("Shared resources initialized.");}

atomic<bool> g_initialized { false };mutex g_mutex;

void processingFunction(){ if (!g_initialized) { unique_lock lock { g_mutex }; if (!g_initialized) { initializeSharedResources(); g_initialized = true; } } print("1");}

int main(){ vector<jthread> threads; for (int i { 0 }; i < 5; ++i) { threads.emplace:back(processingFunction); }}The output clearly shows that only one thread initializes the shared resources:

Shared resources initialized.11111CONDITION VARIABLES

Section titled “CONDITION VARIABLES”Condition variables allow a thread to block until a certain condition is set by another thread or until the system time reaches a specified time. These variables allow for explicit inter-thread communication. If you are familiar with multithreaded programming using the Win32 API, you can compare condition variables with event objects in Windows.

<condition_variable> provides two condition variables:

std::condition_variable: A condition variable that can wait only on aunique_lock<mutex>, which, according to the C++ standard, allows for maximum efficiency on certain platforms.std::condition_variable_any: A condition variable that can wait on any kind of object, including custom lock types.

A condition_variable supports the following member functions:

-

notify_one();Wakes up one of the threads waiting on a condition variable. This is similar to an auto-reset event in Windows.

-

notify_all();Wakes up all threads waiting on a condition variable.

-

wait(unique_lock<mutex>& lk);The thread calling

wait()should already have acquired a lock onlk. The effect of callingwait()is that it atomically callslk.unlock()and blocks the thread, waiting for a notification. When the thread is unblocked by anotify_one()ornotify_all()call in another thread, the function callslk.lock()again, possibly blocking until the lock has been acquired, and then returns. -

wait_for(unique_lock<mutex>& lk, const chrono::duration<Rep, Period>& rel_time);Similar to

wait(), except that the thread is unblocked by anotify_one()call, anotify_all()call, or when the given timeout has expired. -

wait_until(unique_lock<mutex>& lk, const chrono::time_point<Clock, Duration>& abs_time);Similar to

wait(), except that the thread is unblocked by anotify_one()call, anotify_all()call, or when the system time passes the given absolute time.

There are also overloads of wait(), wait_for(), and wait_until() that accept an extra predicate parameter. For instance, the overload of wait() accepting an extra predicate is equivalent to the following:

while (!predicate()) wait(lk);The condition_variable_any class supports the same member functions as condition_variable, except that it accepts any kind of lock class instead of only a unique_lock<mutex>. The used lock class must have a lock() and unlock() member function.

Spurious Wake-Ups

Section titled “Spurious Wake-Ups”Threads waiting on a condition variable can wake up when another thread calls notify_one() or notify_all(), or after a relative timeout, or when the system time reaches a certain time. However, they can also wake up spuriously. This means that a thread can wake up even if no other thread has called any notify member function and no timeouts have been reached yet. Thus, when a thread waits on a condition variable and wakes up, it needs to check why it woke up. One way to check for this is by using one of the versions of wait() accepting a predicate, as demonstrated in the following section.

Using Condition Variables

Section titled “Using Condition Variables”As an example, condition variables can be used for background threads processing items from a queue. You can define a queue in which you insert items to be processed. A background thread waits until there are items in the queue. When an item is inserted into the queue, the thread wakes up, processes the item, and goes back to sleep, waiting for the next item. Suppose you have the following queue:

queue<string> m_queue;To make sure that only one thread is modifying this queue at any given time, we add a mutex:

mutex m_mutex;To be able to notify a background thread when an item is added, we also add a condition variable:

condition_variable m_condVar;A thread that wants to add an item to the queue first acquires a lock on the mutex, then adds the item to the queue, and notifies the background thread. Calling notify_one() or notify_all() can be done whether you currently have the lock or not; both work.

// Lock mutex and add entry to the queue.lock_guard lock { m_mutex };m_queue.push(entry);// Notify condition variable to wake up thread.m_condVar.notify_all();The background thread waits for notifications in an infinite loop, as follows. Note the use of wait() accepting a predicate to correctly handle spurious wake-ups. The predicate checks if there really is something in the queue. When the call to wait() returns, you are sure there is something in the queue.

unique_lock lock { m_mutex };while (true) { // Wait for a notification. m_condVar.wait(lock, [this]{ return !m_queue.empty(); }); // Whenever we reach this line, the mutex is locked and the queue is non-empty. // Process queue item… m_queue.pop();}The “Example: Multithreaded Logger Class” section toward the end of this chapter, provides a complete example on how to use condition variables to send notifications to other threads.

The C++ standard also defines a helper function called std::notify_all_at_thread_exit(cond, lk) where cond is a condition variable and lk is a unique_lock<mutex> instance. A thread calling this function should already have acquired the lock lk. When the thread exits, it automatically executes the following:

lk.unlock();cond.notify_all();LATCHES